This is one of my posts about the history of credibility revolution. Long time readers know that I have a sociological theory that the credibility revolution spread through labor markets, by which I mean student placements. But these student placements “flowed to the top”, meaning three things:

Students placed extremely high in terms of academic placements

Students were placed disproportionately in the United States departments

It spread through labor economics then spread to other fields

Now I’m interested in this as a theory in and of itself, and have a feeling I’ll be doing something with this for the rest of my life. Some people buy beat up cars and spend the weekends fixing it up. I work on this sociological theory about the credibility revolution as a paradigm shift that became so quickly influential not just because of the ideas, but because of supply side student placements into top programs.

But the other part of it is it animates everything I’m about because I’m convinced that there is still to this day a deep segmentation of the market. If I’m right that these ideas required faculty forcing it down people’s throats, but that this movement happened within labor, and even within econometrics it was initially just one part of econometrics, then as you moved away from the top programs, you could go without knowing it.

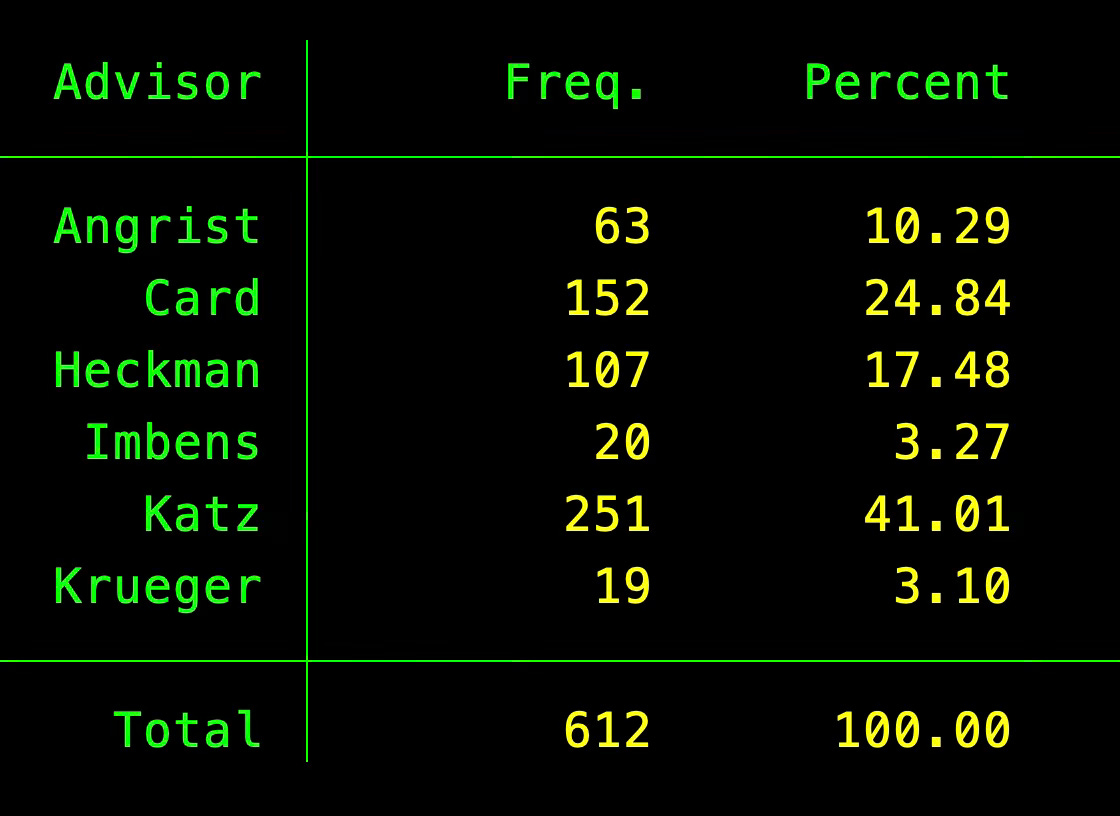

So I emailed Card, Angrist, Orley, Katz, and Imbens and asked for their student lists. I got Heckman’s from his online vita. Unfortunately Orley didn’t keep a list. With some coauthors, I augmented these original lists with data from Proquest. I then worked with an RA and coded up the history of each student’s initial placement by finding their vita online. There were 612 students total in the dataset. I then matched each student’s first placement to that institution’s rank using Repec’s ranking. I wanted to just illustrate this — it’s not causal. It’s just descriptive. But, the patterns are still interesting.

Number of students in my data

My dataset of 612 students from six professors is below. Again, I got these from the economists when I could, and then I used Proquest data to get more. This is partly three of Orley’s prominent “empirical labor economists” students: Jim Heckman, Dave Card, Josh Angrist. But it’s also Alan Krueger because this part of a larger project on the credibility revolution spreading and he’s key. Which is why Guido Imbens is in the list even though Guido is not a labor economist. But he connects to Orley via Angrist, who was an Orley and Card student.

And then I added Larry Katz because while I was interviewing someone about this (I was interviewing one of the students in the list), they said Katz was key to my story. So I wrote him and he pointed me to where I could get his data. I don’t have Claudia Goldin yet, but let’s just say when I realized that the number of Katz’s students was so gigantic, I realized I needed to spend a lot more time just on understanding his advising, which meant I had to spend a lot of time understanding Claudia Goldin’s historical student relationships too. So that’s on the list.

Heckman graduates from Princeton in 1971. I found like three different sources for who his advisors were, and in one it lists 5 people, in another 3 people, and then another I think it was 2 people. I wrote Orley and asked him and without going into details, in the acknowledgements of one of Heckman’s first papers (may have been his JMP), he notes Orley as what seems like an advisor. It’s kind of a complicated story, and I am just going to call him an Orley student.

David Card is also an Orley student. He graduates also from Princeton, but later than Heckman — in 1978. He goes to Chicago for two years, then comes back and stays at Princeton until 1997 when he leaves for Berkeley. He told me in our interview that the cause of his leaving was his wife not getting tenure at Princeton. You can find some information at his wikipedia page.

The rest of these guys graduate right on top of each other after that. Larry Katz graduates in 1985 from MIT. Alan Krueger graduates from Harvard in 1987. Josh Angrist graduates from Princeton in 1989. And Guido Imbens graduates from Brown in 1991.

Now, given that Heckman and Card both graduate in the 1970s and then immediately get assistant professor jobs — Heckman’s first job is at Columbia, Card’s first job is at Chicago, and then both leave after two years to go to Chicago and Princeton, respectively — it is not surprising to see that they have advised so many students. They’ve had a longer opportunity to do so. What’s remarkable is Larry Katz.

Now originally this project was solely about Princeton labor economists plus Guido because I was trying to nail down this particular strand about the credibility revolution. I only added Katz because of an unformed vague knowledge that I knew he belonged because the QJE is so clearly associated with this paradigm shift, he is also is a labor economist, and he fits with the Cambridge part. But it wasn’t until I saw his student numbers that I realized I needed to now pull Claudia Goldin in. She was at Princeton in her first job and is associated with the Section, so I should’ve seen that she fit in the story, but for some reason I don’t usually associate the credibility revolution with Dr. Goldin, so I hadn’t pulled her vita. But I’m in the process of getting it. It’s just going to take me some time as I lost my RA once the summer ended.

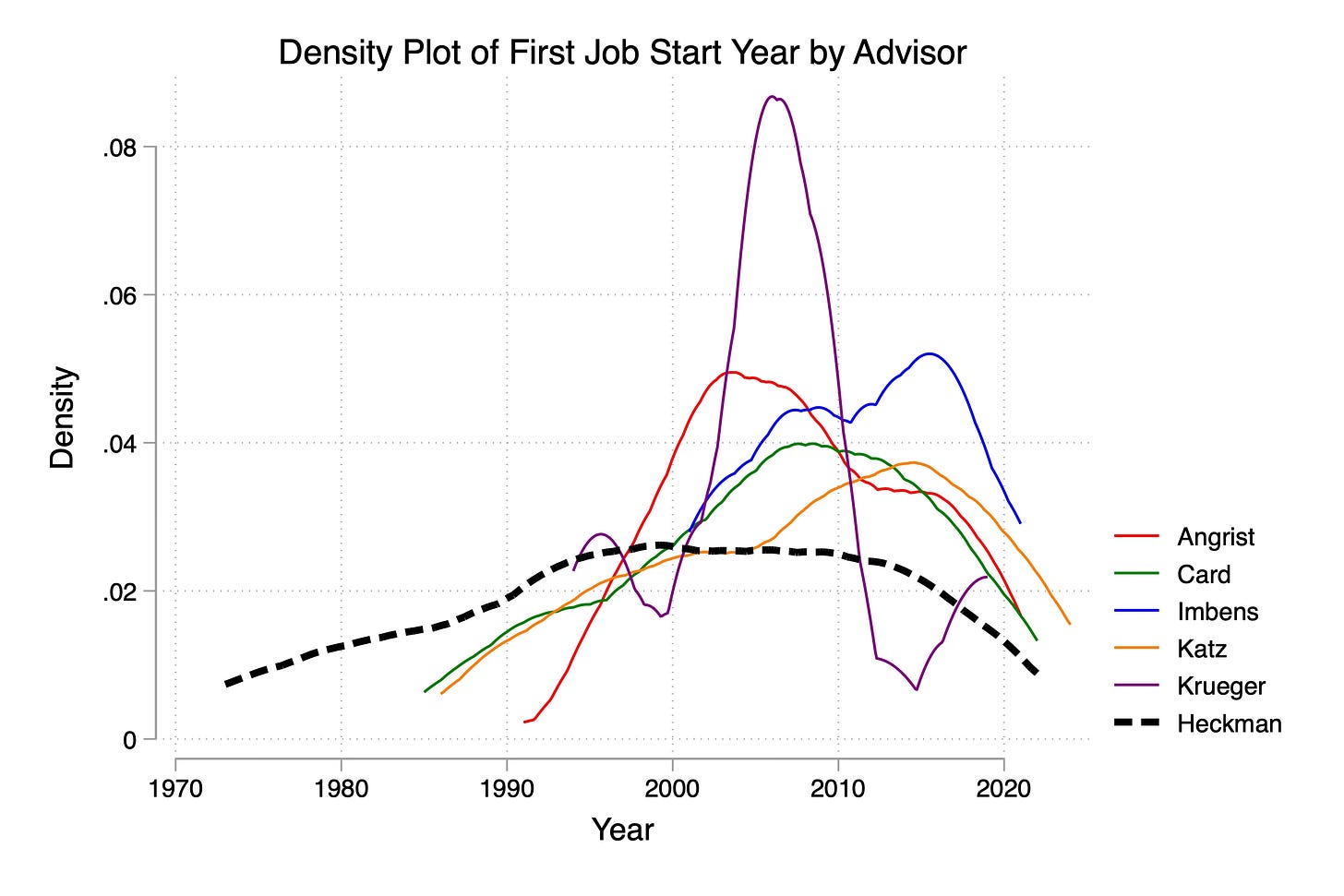

When Do Orley’s Students Place Their Students?

But now let me tell you a little about the space of time when they’re placing their students. I’m going to start by plotting a density plot of when these economists place their students in time. But note this is the distribution of students, by advisor, in the year they get their first job. So you can think of this as “student placements” by year and advisor.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Scott's Mixtape Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.