Claude Code 17: The Zero Profit Condition Is Coming

What happens when everyone in your field gets the same tool you have

I’m going to oscillate between essays about Claude Code, explainers about Claude Code and video tutorials using Claude Code. Today is an essay. Like the other Claude Code posts, this one is free to everyone, but note that after a few days, everything on this substack goes behind a paywall. In the mean time, though, let me show you a progression of pictures of me trying to support the Patriots on Sunday by wearing all of the Boston sports memorabilia I own. Sadly, it did not help at all — or did it? What would the score have been had I not wore all this I wonder?

Thank you everyone for supporting this substack! For only the cup of a coffee every month, you too can get swarms of emails about Claude Code, causal inference, links to a billion things, and pictures of me wearing an apron. So consider becoming a paying subscriber!

Here’s the thing about positive surplus in competitive markets: it doesn’t last.

Tyler Cowen has this move he’s been doing for years. Whenever something disruptive shows up — crypto, remote work, AI — he asks the same question: What’s the equilibrium? Not the partial equilibrium. Not your best response. The Nash equilibrium — where everyone is playing their best response to everyone else’s best response, and nobody has any incentive to deviate. Where does this thing settle?

I’ve been using Claude Code since mid-November. I remember the first time — I used it to fuzzy impute gender and race in a dataset of names. I thought I was just looking at another chatbot. But I kept using it, kept taking more steps, and kept being stunned at what I was doing with it. By late November, I’d used it on a project that was sufficiently hard, and that was when I knew. The speed, the range of tasks, the quality — it did not have an easily discernible upper bound. More work, less time, better work — but also different work. Tasks I wouldn’t have attempted because the execution cost was too high suddenly became feasible. Some combination of more, faster, better, and new at all times. It was, for me, the first real shift in marginal product per unit of time I’d experienced, even counting ChatGPT. I felt a genuine urgency to tell every applied social scientist who would listen: You have to try Claude Code. You have to trust me.

But here’s the thing about being an economist. You can feel enormous surplus and simultaneously know that surplus is exactly what competitive forces eat. In competitive markets, anyone who can enter will enter, so long as their expected gains exceed the costs of entry. They keep entering until the marginal entrant earns zero economic profit. The question isn’t whether Claude Code is valuable right now. The question is what happens when everyone in your field has it.

I think four things happen.

The surplus gets competed away — but the work gets better

The zero profit condition is not a theory. It’s closer to a force of nature. You see it in restaurants, in retail, in academic subfields. Wherever surplus is visible and barriers are surmountable, people show up. And when enough people show up, the surplus gets competed away.

Think about spreadsheets. When VisiCalc and then Lotus 1-2-3 arrived, the early adopters had an enormous advantage. Accountants who could use a spreadsheet were worth more than accountants who couldn’t. That advantage was real and large. But it didn’t last, because the barriers to learning spreadsheets were low and the benefits were visible. Eventually everyone learned spreadsheets. The competitive advantage disappeared. But accounting got better. The work itself improved. The equilibrium wasn’t higher rents for spreadsheet users. It was higher quality work across the board, at the same compensation.

I think that’s where Claude Code is headed for applied social science — but I want to be honest about what “the work gets better” actually means, because the evidence is not as clean as the enthusiasm suggests. A pre-registered RCT by METR found that experienced open-source developers were 19% slower with AI coding tools on their own repositories. And here’s the part that should make every early adopter uncomfortable: those developers believed they were 20% faster. The perception-reality gap was 39 percentage points.

Now — important caveats. That study had 16 developers using Cursor Pro, not Claude Code, on mature software repositories they already knew intimately. These were not applied social scientists doing empirical research. The external validity to our context is genuinely uncertain. But the finding that people systematically overestimate their AI-assisted productivity is worth sitting with, because none of us are exempt from that bias. CodeRabbit’s analysis of 470 GitHub pull requests found AI-generated code had 1.7 times more issues than human-written code. And Anthropic’s own research found that developers using AI scored 17% lower on code comprehension quizzes than those who coded by hand.

But the spreadsheet analogy actually predicts this. Spreadsheets didn’t just make accounting better — they also created entirely new categories of error. Circular references. Hidden formula mistakes. The Reinhart-Rogoff Excel error that influenced European austerity policy. Every productivity tool creates new failure modes alongside genuine improvements. The honest prediction for AI in research is probably this: the ceiling of what’s possible rises, the floor of quality rises for people who previously couldn’t do the work, and a new category of AI-assisted error emerges that we will need norms and institutions to catch. The work gets better on average. But overconfidence is a real and present risk, especially for people who already know what they’re doing.

The gains are largest where they’re needed most

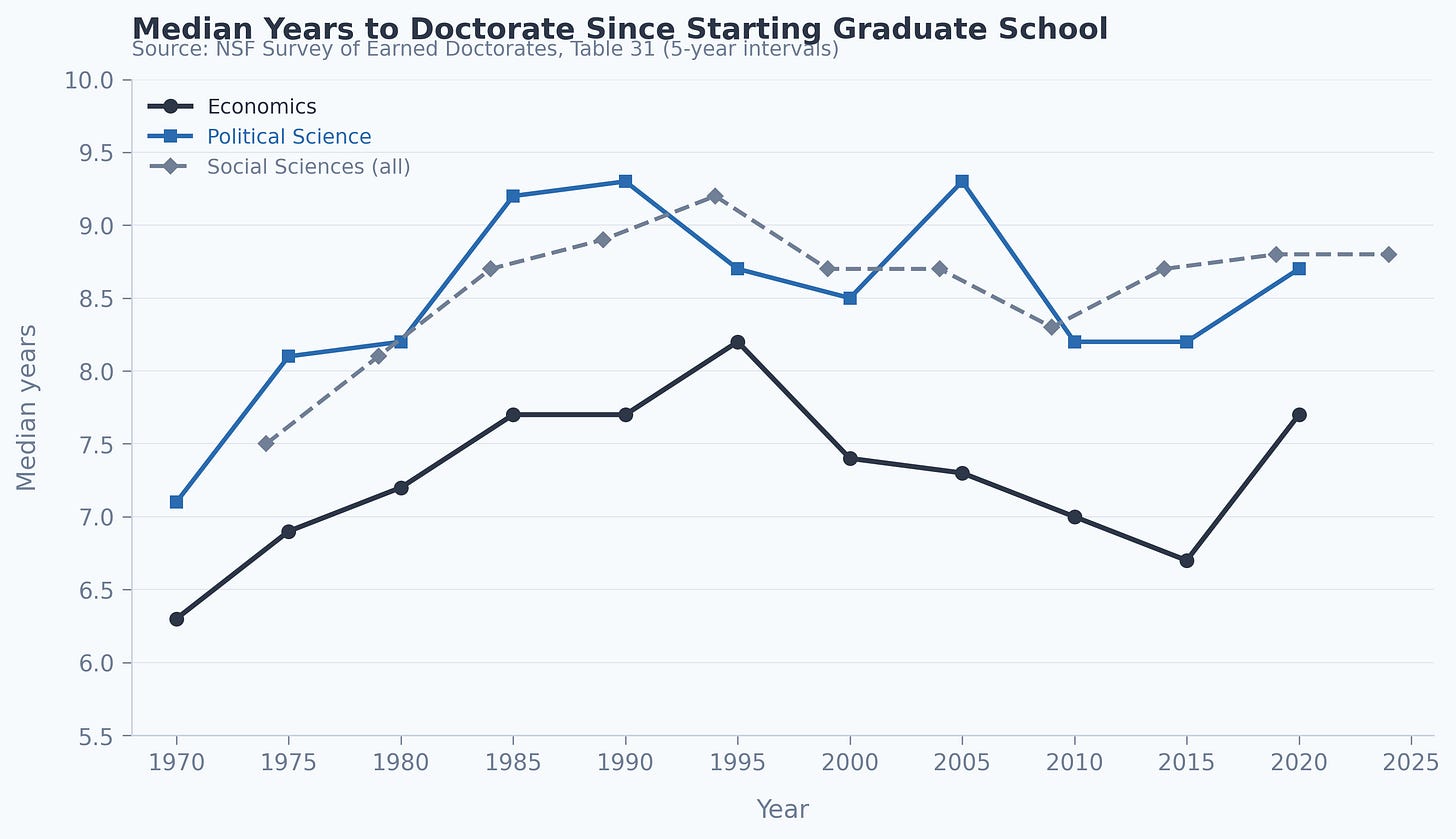

Look at the figure. The NSF’s Survey of Earned Doctorates shows that the median economics PhD takes about 6.5 to 7.5 years from starting graduate school — it peaked at 8.2 years in 1995, fell to 6.7 by 2015, and jumped back to 7.7 in 2020 (most likely driven by delays caused by the pandemic’s effect on the market for new PhDs). Political science has even longer times, ranging from 8 to 9 years. Stock, Siegfried, and Finegan tracked 586 students who entered 27 economics PhD programs in Fall 2002 and found that by October 2010, only 59% had earned their PhD — 37% had dropped out entirely.

That was before AI agents. And it was before the economics job market collapsed. Paul Goldsmith-Pinkham’s tracking of JOE postings shows total listings fell to 604 as of November 2025 — a 50% decline from 2024 and 20% below COVID levels. Federal Reserve and bank regulator postings: zero. Not low. Zero. EconJobMarket data shows North American assistant professor positions down 39% year-over-year. Roughly 1,400 new economics PhDs are now competing for about 400 tenure-track slots.

Add the enrollment cliff — WICHE projects a 13% decline in high school graduates from peak through 2041 — and the NIH overhead cap that would redirect $4 to $5 billion annually away from research universities, and you have a profession being squeezed from every direction simultaneously.

Now consider the evidence on who AI helps. None of these studies are about Claude Code specifically — we don’t yet have RCTs on AI agents for applied social scientists, and that absence is itself worth noting. But the pattern across adjacent domains is consistent. Brynjolfsson, Li, and Raymond studied nearly 5,200 customer support agents using GPT-based tools (QJE 2025) and found that AI increased productivity by 14% on average — but by 34% for the least experienced workers. Two months with AI equaled six months without it. Mollick and colleagues found the same pattern at Boston Consulting Group using GPT-4: 12.2% more tasks, 25.1% faster, 40% higher quality — with below-average performers gaining 43% versus 17% for top performers. But — and this is crucial — when consultants used GPT-4 on analytical tasks requiring judgment outside the AI’s capability frontier, they performed 19 percentage points worse than consultants without AI. Mollick calls this the jagged frontier. There are tasks where AI makes you better and tasks where it makes you worse, and you cannot always tell which is which in advance. Those were GPT-3 and GPT-4 era chatbots — not agentic tools like Claude Code that can execute code, manage files, and run multi-step research workflows. Whether that distinction narrows or widens the frontier is an open empirical question.

I want to be careful here, though, because there’s a meaningful question about whether any of these studies tell us what we need to know about Claude Code specifically. Claude Code is not a chatbot. It is an AI agent — it runs on your machine, executes code, manages files, searches the web, builds and debugs multi-step research workflows autonomously. The Brynjolfsson study was about a GPT-3.5 chatbot assisting customer support reps. The Mollick study was about GPT-4 answering consulting prompts. The METR study was about Cursor Pro, an AI coding assistant, on software repositories. None of them studied what happens when an applied social scientist has an agent that can independently clean data, run regressions, build figures, check replication packages, and iterate on all of it. We simply don’t have that study yet. The external validity from chatbots and code assistants to agentic research tools is genuinely uncertain, and anyone who tells you otherwise is guessing.

What we can say is this: the consistent pattern across every adjacent study is that AI helps the least experienced the most, on tasks within the frontier. Graduate students — who have the least experience, the most to learn, and the worst job market in modern memory — are the population most likely to benefit, whatever the magnitude turns out to be. The case for getting these tools into their hands doesn’t require believing AI helps everyone equally, or even knowing the precise effect size. It requires believing the direction is right. And on that, the evidence across every domain points the same way.

Good ideas won’t wait — but neither should your judgment

I’ve always believed in an efficient market hypothesis for good ideas. Not ideas in the abstract — specific, actionable research opportunities. The natural experiment you noticed. The dataset nobody else has used. The policy variation that creates clean identification. If competitive capital markets hack away opportunities until we should be surprised to find a dollar on the ground, why wouldn’t the same be true for research ideas? In a competitive academic market, truly great ideas don’t sit around unclaimed for long unless some barrier protects them.

The only thing that protected me from being constantly scooped was that I worked in an area most people found repugnant — the economics of sex work. For years I was largely off alone with maybe ten other economists. All of us were either coauthors or sufficiently spread out that we didn’t overlap. Repugnance was my barrier to entry — social, not informational or financial. It’s why it was such a shock when, one day in the spring of 2009, I read in the Providence Journal that Rhode Island had accidentally legalized indoor sex work twenty-nine years earlier, and a judge named Elaine Bucci had ruled it legal in 2003. I wrote Manisha Shah and said holy crap. That project took nine years of my life.

But repugnance is endogenous. It’s a feeling, not a government-mandated monopoly permit. And a tool like Claude Code doesn’t just compress time — it changes what you’re willing to attempt. It finds data sources you didn’t know existed. It writes and debugs code for empirical strategies you wouldn’t have tried because the execution cost was too high. It builds presentations and documentation that used to take days. The window for any given research opportunity is shrinking not just because people can work faster, but because the set of tasks people are willing to undertake has expanded. The same tool that lets you do more lets everyone else do more.

Now — how much compression are we actually talking about? Acemoglu’s task-based framework is the right way to think about this: AI doesn’t automate jobs, it automates tasks, and the aggregate effect depends on what share of tasks it can profitably handle. He estimates about 5% of economic tasks and a GDP increase of roughly 1.5% over the next decade. The Solow Paradox — you can see the computer age everywhere except in the productivity statistics — may well repeat. The research production function may not shift as dramatically as it feels from the inside.

But even if the compression is more modest than it feels, the direction is clear. Execution barriers are falling. If you have a genuinely good idea and the data is accessible, the expected time before someone else executes it is shorter than it was two years ago. You may not need to panic. But you probably shouldn’t sit on it either. Whether the competitive pressure on ideas is increasing by a lot or a little, the best response is the same: move.

Your department should be paying for this

So if the equilibrium involves widespread adoption, what’s slowing it down? Price.

Claude Max costs $100 a month for 5x usage or $200 a month for 20x. To use Claude Code seriously — all day, across research and teaching — you need Max. The lower tiers hit rate limits that destroy momentum at the worst moments. Imagine if R or Stata simply stopped working without warning while you were in a flow state under a deadline. That’s what the $20/month tier feels like. Two hundred dollars a month is $2,400 a year. Graduate student stipends run $25,000 to $35,000 before taxes. That’s 8 to 10% of after-tax income. The people who would benefit most — the least experienced, the evidence says — are the ones least able to afford it.

The economics of the solution are textbook. Graduate students have lower willingness to pay. Marginal cost of serving them is near zero at Anthropic’s scale. You can’t resell Claude Code tokens — no arbitrage is possible. These are the exact conditions for welfare-improving third-degree price discrimination. Anthropic already has a Claude for Education program, with Northeastern, LSE, and Champlain College as early adopters. Good. But push harder — work directly with graduate departments, not just universities. Get PhD students on Max-equivalent plans at prices their stipends can absorb.

But this isn’t only Anthropic’s problem. Departments should be building Max subscriptions into PhD funding packages. The ROI is straightforward: if the Brynjolfsson and Mollick numbers hold even partially for tasks within the frontier, we’re talking meaningful improvements in speed and quality for the students who need it most, plus faster time to degree — saving a year of stipend, office space, and advising bandwidth for every year shaved. A Max subscription is $2,400 a year. That’s less than one conference trip. In a market where JOE postings are down 50% and funding is under threat from every direction, anything that makes your students more competitive and your program more efficient is not optional. If I were a department chair, this is what I’d be working on right now.

And for faculty: if your university won’t allow you to run Claude Code on their machines — and my hunch is most won’t, once they understand what AI agents actually do on a system — then get your own computer and your own subscription. Universities lag on everything. They won’t let you have Dropbox. They won’t let you upgrade your operating system. They are not going to be fine with an AI agent executing arbitrary code on their network. That is their right. But it means you may have to do your real work on your own machine. This isn’t dystopian. This is probably this fall.

There is no scenario

So where does this leave you? Two scenarios.

In the first, adoption stays slow. Repugnance and opposition towards AI persists, institutional inertia wins, most of your peers don’t adopt. In that world, early adopters maintain positive surplus for a long time. You’re strapped to a jet engine while everyone else pedals.

In the second, adoption accelerates. Norms shift, prices fall, tools improve. Most of your peers adopt. Now the surplus gets competed away, and the cost of not adopting becomes actively negative.

This is not an essay claiming AI will transform everything. The evidence is more complicated than that. The gains are uneven. Experienced researchers may not benefit as much as they think — and they are particularly bad at knowing when AI is helping versus hurting. Judgment-heavy tasks remain stubbornly human. The macro productivity effects may be modest. But the equilibrium logic doesn’t care about any of that. It doesn’t require everyone to gain equally. It requires enough people to gain enough that non-adoption becomes costly. And the answer to that is almost certainly yes. Wendell Berry refused to use a computer to write. He was the exception, not the equilibrium.

In both scenarios, the best response is the same: adopt. The payoff matrix is asymmetric. The downside of adopting early is small — you spent some money and time learning a tool. The downside of not adopting while others do is large — you’re less productive than your competition in a market where the zero profit condition will not be kind to you.

There is no scenario in which I am not paying for Max.

Great post Scott and I agree that this is a huge opportunity for social scientists and just research in general. Do you think there'll be any issues in terms of journals accepting analysis done using Claude Code, though? For me personally, I'm genuinely thinking about moving a lot of my research beyond the paywalled barriers of expensive academic journals and into Substack instead, where it can genuinely make a difference, or is this just potentially career silliness on my behalf?

"But the equilibrium logic doesn’t care about any of that. It doesn’t require everyone to gain equally. It requires enough people to gain enough that non-adoption becomes costly."

Members of some organizations can enforce what are effectively prohibitions or cartels against adoption. This is especially costly if there are network effects to returns on adoption. I don't think academia is such a case, but you can imagine other types of organizations where it is true!