Claude Code Changed How I Work (Part 2)

The Theory of Attention and the Danger Zone

This is Part 2 of a multi-part series on using AI agents for economics research. Part 1 introduced the landscape. This entry develops the theory underlying a lot of the arguments I’ll make in subsequent posts, but this is also a theory I’ve been posting about it for a year or two on here. I just wanted it all in one place, plus I wanted to show you the cool slides I made. This is also based on a talk I gave at the Boston Fed Monday, and I just wanted to also lay out that talk in case anyone wanted to read it too. Some of it gets a little repetitive, plus some of you have seem me write about this or present on it, but like I said, I wanted to get it down on paper.

The Production of Cognitive Output

Let’s start with something familiar to economists: a production function.

Cognitive tasks---research, code, analysis, homework---are produced with two inputs:

H = Human time

M = Machine time

The production function is simply:

The question that matters for everything that follows is: What is the shape of the isoquants?

Pre-AI: The World of Quasi-Concave Production

For producing gadgets and widgets, the idea is that we work with production functions that take capital and labor, mix it together, and get gadgets and widgets. But that’s noncontroversial when it comes to gadgets and widgets, more or less things, physical stuff. But what about cognitive output? What about homework, research, ideas, art? What best describes those production functions?

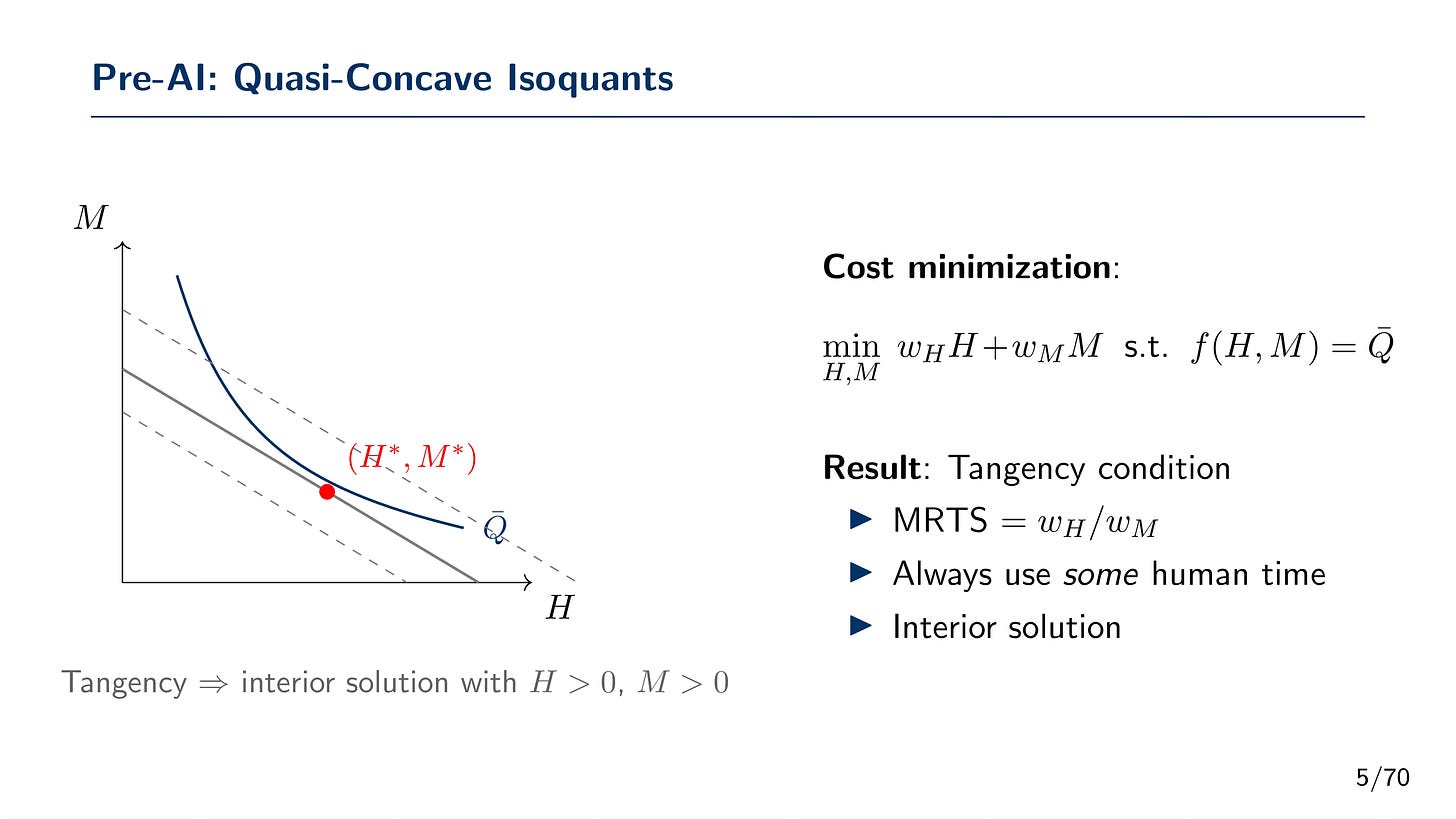

Before AI, the production of cognitive output had a standard property: quasi-concave production functions with concave isoquants. Why? Well, this is a foundational assumption in microeconomics, and it held for good reason. We tend to think that you can’t do anything without using at least some labor, and so in core micro theory, you usually motivate production by specifying production functions that satisfy that property, of which quasi-concave is one.

So let’s specify now that one produces cognitive output, not with factories and steam engines, but with human time inputs as well as machine time inputs (usually thought to have an opportunity cost and that we rent on the market as such). What does quasi-concavity mean here? It means that the isoquants curve toward the origin but they also never touch the x (human time inputs) and y (machine time inputs) axes. To produce any cognitive output at all---to complete any homework assignment, to write any research paper---you needed some human time. Always. How much depends on the cognitive output, but quasi-concavity means that you will, no matter the relative prices of machine and human time, need at least some of both.

So look at the above picture of an isoquant cut from the belly of a quasi-concave production function. It’s curved like I said and as it’s a fixed isoquant, we can think of it as some research output, like a song, a scientific paper, or homework. The cost of producing it is the weighted sum of human time (H) and machine time (M) where the weights are the prices/wages of renting that time at market prices. And the solution for a profit-maximizing firm is to choose to make that particular output, Q-bar), using an optimal mix of machine and labor time that minimizes cost subject to being on that isoquant, which is to set the marginal rate of technical substitution (MRTS) equal to the relative prices of human to machine time. Given the isoquant is curved, but the cost function is a straight line, we end with an interior solution using at least some machines and some human time.

Now what is the use of machine time before AI exactly that is being used to produce cognitive output? Maybe it’s a guitar. Maybe it’s a calculator, a word processor. It’s statistical software that inverts matrices for you so that you aren’t spending the rest of your life inverting a large matrix by hand. The machine does a task you once did manually.

But the key is that human time was always strictly positive. You couldn’t produce cognitive output without spending time thinking, struggling, learning.

Post-AI: The World of Linear Isoquants

So, I don’t think it is controversial in December 2025 to state what I think is the obvious which is that generative AI has radically changed the production technologies for producing cognitive output. Just what it has done, and how it has done it, and whether it has made it better is things people debate, but undoubtedly it has. We need only look at papers finding a lot of “ChatGPT words” showing up in papers — people are using generative AI to do scientific work. So something has changed.

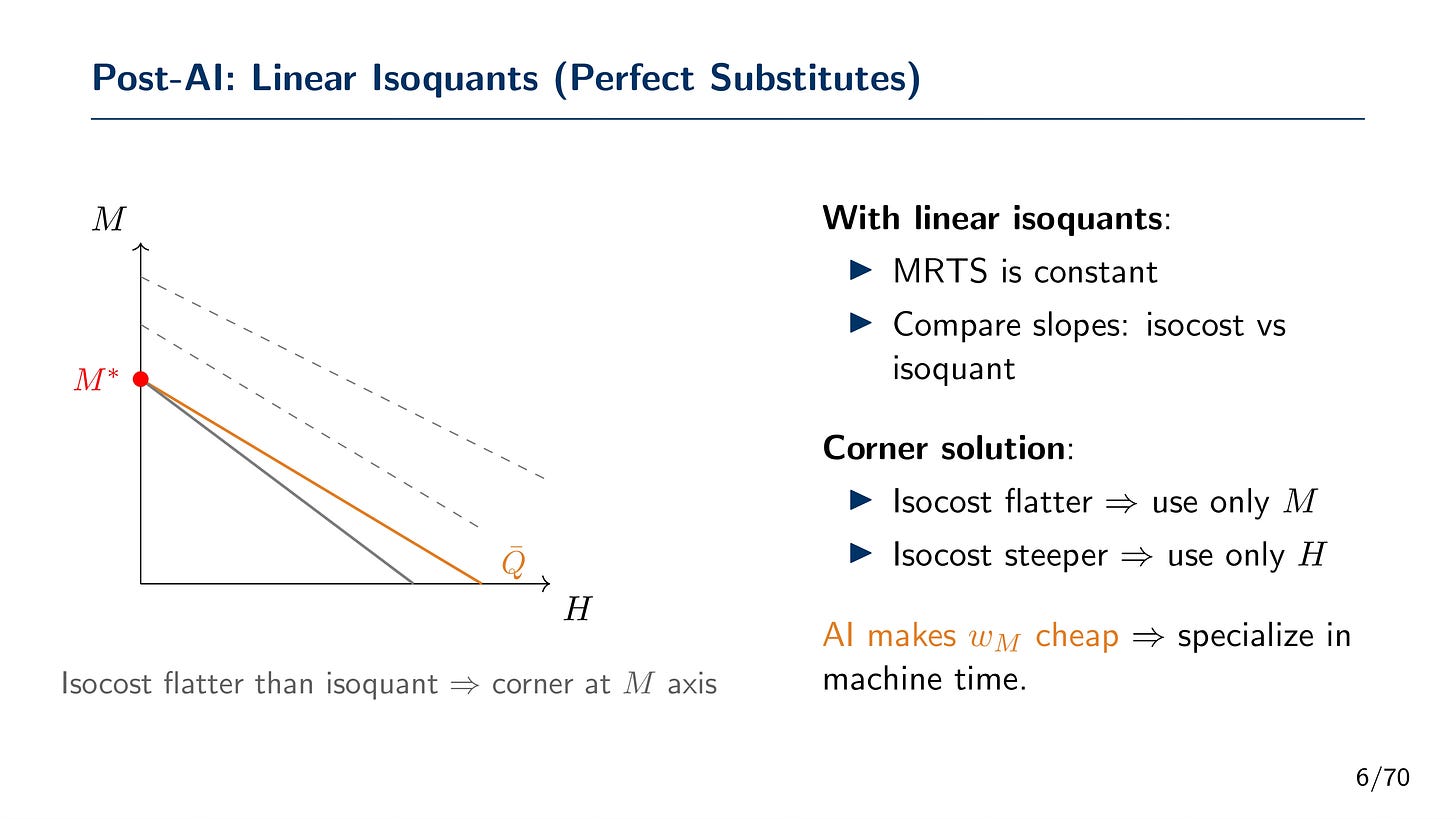

For the purpose of my theory, I will frame it in production terms. For many cognitive tasks, the isoquants are no longer quasi-concave.

They’re now linear isoquants. And that has huge consequences.

When production functions produce linear isoquants, it means machine time and human time are perfect substitutes.

And this changes everything about cost minimization.

With linear isoquants, the tangency condition no longer applies. Instead, you compare slopes. The isocost line has slope -w_H/w_M. The isoquant has slope -a/b. If they’re not equal---and generically they won’t be---you get a corner solution, which means that the rational, profit-maximizing scientist/artist/creator will choose the cheapest amount of human or machine time — not some of both. One or the other.

If the isocost is flatter than the isoquant: use only M.

If the isocost is steeper than the isoquant: use only H.

And here’s what’s happened in my opinion: AI has made w_M extraordinarily cheap. The cost of machine time for cognitive tasks has collapsed. Particularly given these are prices at the margin of time use, not the total or average cost. And since we pay for gen AI on a subscription basis, not a per-use basis, gen AI will always be less expensive than human time which has at worst a leisure-based shadow price. That is unless we start taxing gen AI at the margin, that is, but that’s for another post.

So the rational cost-minimizer chooses the corner: H = 0 (zero human time inputs), M > 0 (all machine time inputs). For the first time in human history, we can produce cognitive output with zero human time.

The Problem: Human Capital Requires Attention, Attention Requires Time

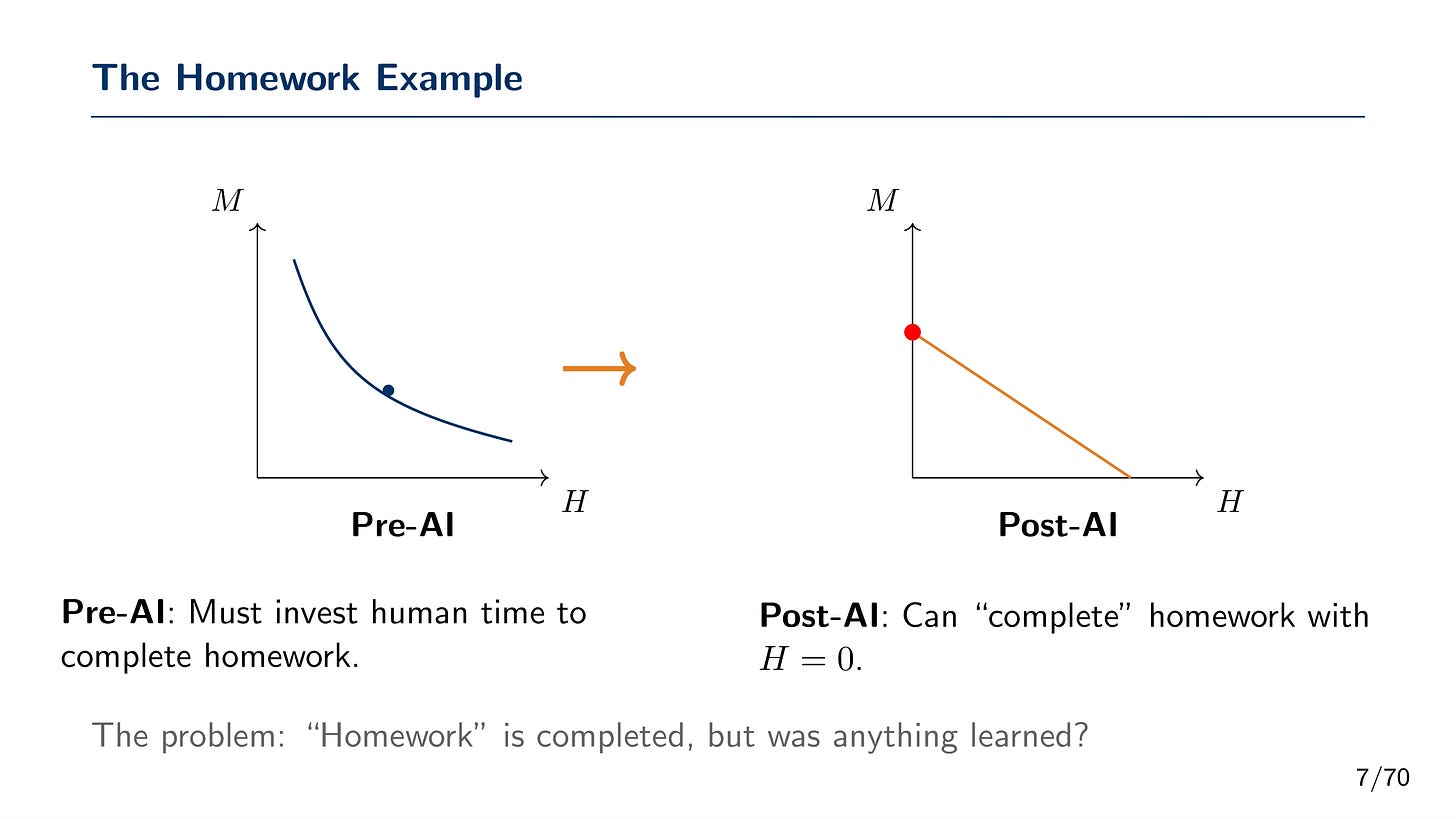

Here’s where the theory gets interesting---and troubling. I’ll use my favorite example here — homework. The student must produce homework, which is a particular kind of output produced by students, prescribed by teachers. The homework gets “completed.” The research report gets “written.” But was anything learned?

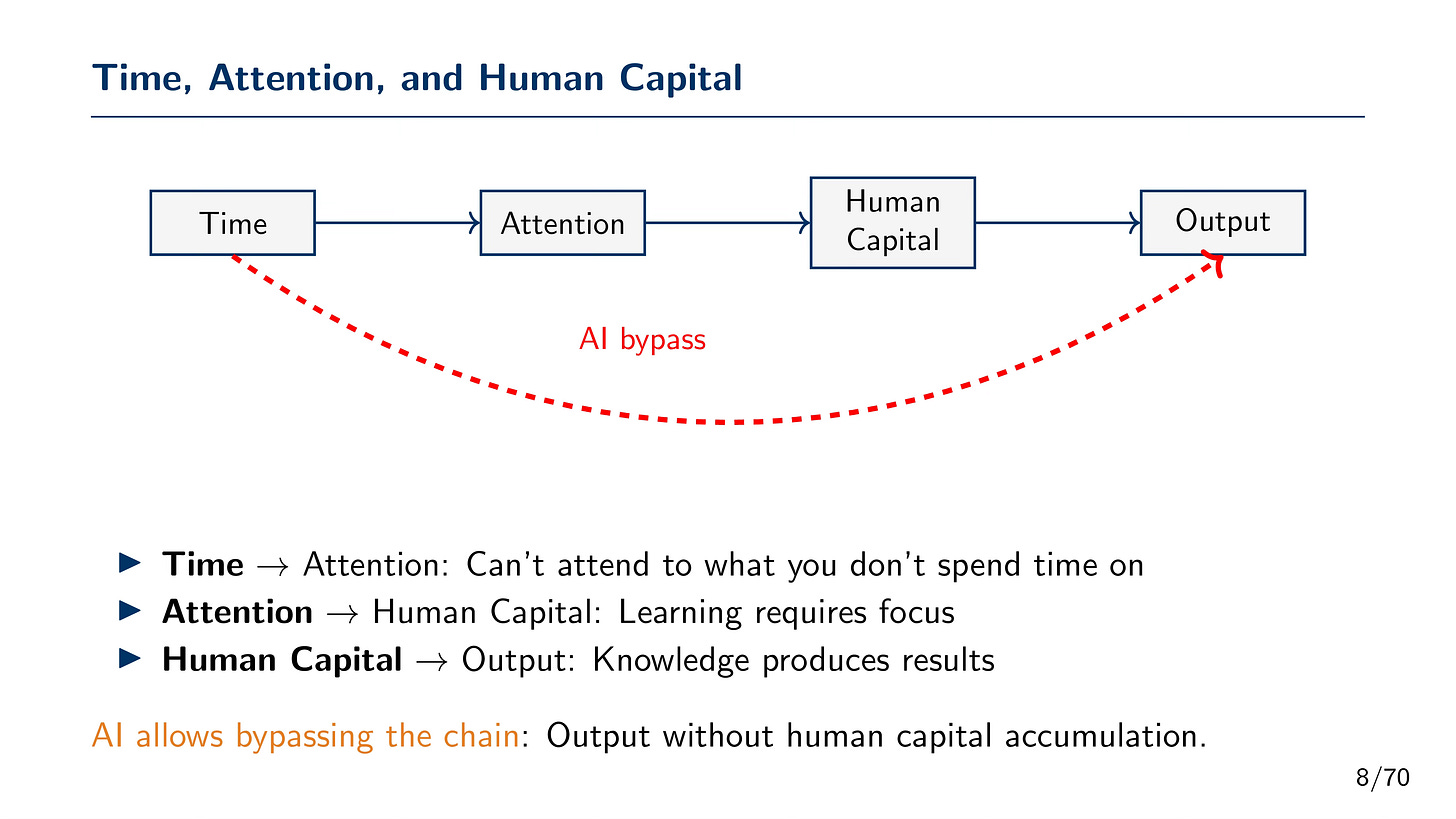

Human capital is not produced by magic. It’s produced through a specific chain shown in this slide.

Each link in this chain is essential to producing cognitive output. Note the direct effects between time, attention, knowledge, and finally, the output itself.

Time → Attention: You cannot attend to what you do not spend time on. Attention is time directed narrowly at intellectual puzzles.

Attention → Human Capital: Learning requires focus. Struggle is pedagogically necessary. The difficulty is the point.

Human Capital → Output: Knowledge produces results. Expertise enables judgment.

But AI creates a bypass. It offers a direct route:

AI → Output

No human time. No attention. And no human capital accumulation. Just output. We get research output (e.g., songs, homework, scientific papers) without human capital accumulation.

This bypass is extraordinarily efficient for producing output. But it severs the connection between production and learning. We can now complete the homework without doing the homework. We can produce the research without understanding the research.

Two Pathways to Cognitive Output

Let me state this more formally. There are now two distinct production pathways:

Pathway 1 (Traditional):

Pathway 2 (AI Bypass):

Pathway 1 is slow, costly, and produces both output and human capital as joint products. Pathway 2 is fast, cheap, and produces output only. So, we need to ask ourselves — do we care about output only? Do we care about human capital only? Do we care about both?

Reasonable people will no likely have different opinions on that, as to frame it that way in terms of preferences is to immediately invite the impossibility of reconciling those preferences. There is likely single answer to that. Some will not like where we are going, where machines produce our songs and scientific papers, and some will love it. But my point is more positive for now and that is to simply point out that a rational agent facing linear isoquants and relatively cheap machine time will always choose Pathway 2 because at the margin, they should! That’s what cost minimization tells us.

But here’s the paradox: the choice that minimizes cost for any single task may maximize costs across a lifetime of tasks. Human capital depreciates. Skills atrophy. And if you’re just starting out---a student, an early-career researcher---you may never acquire the human capital in the first place.

So Should We Care? The Productivity Curve and the Danger Zone

Let me show you how this plays out dynamically. And in my framing, you’ll probably be able to tell that I am somewhere in the middle normatively between a purely Luddite approach of eschewing the use of AI for producing cognitive output entirely and allowing it to go completely unchecked.

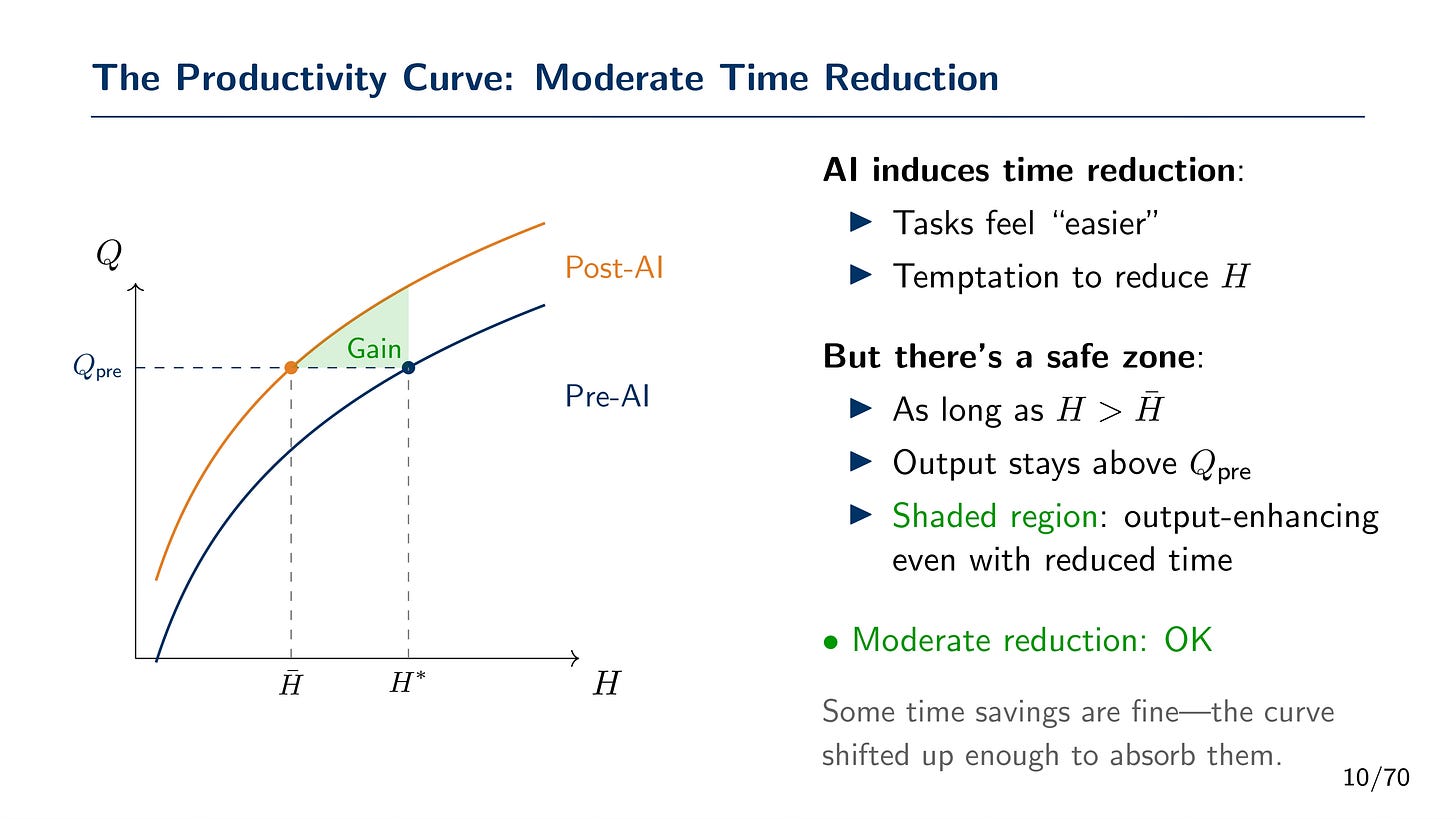

First I will consider that holding fixed capital and machine time, the production of cognitive output will exhibit diminishing marginal returns to human time. But, I will simply assert that perhaps AI will shift the productivity curve upward. For any given amount of human time H, in other words, you can now produce more output Q than before.

If you maintain your human time at the pre-AI level H*, you capture pure productivity gains. Same time, more output. This is unambiguously good. I have written about this before, but just am saying it again so you can see that pretty graphic!

But here’s the temptation: if tasks feel easier, why not reduce human time? The curve shifted up, so surely you can afford to dial back.

And indeed, there’s a safe zone. It’s safe in that a person is reducing time towards cognitive outputs and yet their own personal human capital accumulation has grown. That seems like win-win if you are contemplating it relative to a counterfactual. You can reduce human time somewhat and still end up producing more than before. The upward shift absorbs some of the reduced input.

But there’s a threshold. Call it H-bar.

Below that threshold lies the danger zone.

In the danger zone, you’ve reduced human time so much that despite the productivity-enhancing technology, you’re actually producing less than you did before AI. The behavioral response overwhelms the technological improvement.

This is the paradox: a productivity-enhancing technology can make us worse off if it induces too much substitution away from human input. This is something Ricardo notes in the third edition of his book, it’s something Malthus had noted, it’s something that Paul Samuelson wrote about, and it’s something that contemporary economists like Acemoglu, Johnson and Restrepo have all noted. And this has relevance insofar as human capital continues in long run equilibrium to determine wages. The wealth of nations versus the wages of nations.

Why This Might Be Different

You might object: Haven’t we always offloaded cognitive work to machines? I don’t invert matrices by hand. I don’t look up logarithm tables. My computer does those things, and I don’t worry about my matrix-inversion human capital depreciating.

Fair point. But I think this time is different, for a specific reason.

When we offloaded matrix inversion to computers, we offloaded a *routine* subtask within a larger cognitive process that still required human time and attention. The economist still had to specify the model, interpret the results, judge whether the assumptions were plausible. The computer was a tool within a human-directed workflow.

What’s new about AI is that it can handle the *entire* cognitive workflow. Not just the routine subtasks, but the judgment, the interpretation, the specification. You can ask it to “write a paper about X” and it will produce something that looks like a paper about X.

This means the cost of producing cognitive output drops toward zero. And when the cost drops toward zero, the question becomes: Who is the marginal researcher? What happens to overall human capital in the economy when cognitive output can be produced without human cognition?

The Attention Problem

Let me dig deeper into attention, because I think it’s the crux of the matter.

Attention is not free. It’s costly and resource-intensive. It uses the mind’s capacity. It requires time directed narrowly at intellectual puzzles, often puzzles that are frustrating, confusing, and difficult.

But attention is also the key to discovery. Scientists report this universally: they love the work. They love the feeling of discovery. There’s an intellectual hedonism in solving hard problems, in understanding something that was previously mysterious.

When we release human time from cognitive production, we necessarily release attention. You cannot attend to what you don’t spend time on. And when attention falls, the intrinsic rewards of intellectual work disappear. What’s left are the extrinsic rewards---financial incentives, career advancement, publications.

If intrinsic rewards fade and only extrinsic rewards remain, then the use of AI for cognitive production becomes dominant. Humans become managers of the process, pushing buttons, but nothing more.

Maybe this is fine. Maybe we’re comfortable being managers. Maybe the outputs matter more than the process.

But I suspect something is lost. The joy of understanding is lost. The depth of expertise is lost. And eventually, the ability to verify and direct the AI may be lost, because verification requires the very human capital that the AI bypass prevents us from accumulating.

Who watches the watchers, when the watchers no longer understand what they’re watching?

Coming Soon: The Setup for Part 3 in My Series

So here’s where we are:

The Productivity Zone: Human time is maintained. Attention is preserved. Human capital accumulates. Output improves. AI augments the human process.

The Danger Zone: Human time collapses. Attention disappears. Human capital depreciates or never forms. Output may even decline despite better technology.

The difference between these zones is not the technology. It’s the behavioral response to the technology. It’s whether humans maintain engagement or release it entirely.

In the next entry, I’ll argue something that may seem paradoxical: AI agents---not chatbots, not copy-paste workflows, but true agentic AI that operates in your terminal and executes code---may actually be *better* for preserving human attention than simpler generative AI tools.

Why? Because agents require supervision. They require direction. They require you to understand enough to verify what they’re doing. The “vibe coding” approach---copy code from ChatGPT, paste, run, copy error, paste, repeat---requires almost no attention. You’re a messenger between the AI and your IDE.

But working with an AI agent is more like managing a brilliant but junior collaborator. You have to know what you want. You have to evaluate whether what it produces makes sense. You have to catch its mistakes. This is cognitively demanding. And that demand may be exactly what keeps us on the right side of the curve.

Most of us don’t have an Ivy Leaguer’s access to an army of brilliant predocs, RAs, and project managers. Most of us don’t have a well-endowed lab like Raj Chetty. But I think AI agents give us all three---predocs, project managers, and RAs---and suddenly we’re at a radical shift in our personal production possibility frontiers.

The key won’t be merely the technology. It will be **innovative workflows** that maintain human engagement while leveraging machine capability.

More on that next time.

These slides are from a talk I gave at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston in December 2025. The deck was produced with assistance from Claude Code (Anthropic’s Claude Opus 4.5).