This is all a work in progress. I saw Antonio Mele from LSE publish his adaptation of Boris Cherny’s workflow principles, and I thought I would do the same. If these tools are useful to me, maybe they’ll be useful to others. Take all these with a grain of salt but here it nonetheless is. Thank you all for your support of the podcast! Please consider becoming a paying subscriber!

I’ve been using Claude Code intensively since the second week of November, and I’ve developed a workflow that I think is genuinely different from how most people use AI assistants. I’ve had people ask me to explain it in general, as well as explain more specific things too, so this post explains that workflow and introduces a public repo where I’m collecting the tools, templates, and philosophies I’ve developed along the way.

The repo is here: github.com/scunning1975/MixtapeTools

Everything I describe below is available there. Use it, adapt it, ignore it—whatever works for you. I fully expect anyone who uses Claude Code to, like me, develop their own style, but I think some of these principles are probably always going to be there for you no matter what.

The Core Philosophy: Thinking Partner, Not Code Monkey

I think a lot of people use AI coding assistants like it is a trained seal: tell AI what you want, the AI writes it, done. This is kind of a barking orders approach, and it’s not really in my opinion very effective in many non-trivial cases. I use Claude Code differently. I treat it as a thinking partner in projects who happens to be able to write code.

The difference:

Typical use: “Write me a function that does X”

My use: “I’m seeing Y in the data. What could explain this? Let’s investigate together.”

This distinction matters enormously for empirical research. The hard part isn’t writing code—it’s figuring out what code to write and whether the results mean what you think they mean. And having someone or some thing to be in regular interaction with as you reflect on what you’re doing, why you’re doing it, and what you’re seeing is, I think, important for successful work.

Claude Has Amnesia

But, here’s the fundamental problem with Claude Code: Claude Code forgets everything between sessions. It forgets everything in the same project whenever you start a new chat interface with that project. It’s easy to forget that because of the continuity of the voice, and because it does not know what it does not know. But it is important that you remember that every time you open the same project from a new terminal, or you initiate a new project from a new terminal, you’re starting from zero context.

Most people deal with this by re-explaining everything verbally. I deal with it by building external memory in markdown files. Every project has:

CLAUDE.md— Problems we’ve encountered and how we solved themREADME.mdfiles — What each directory contains and whySession logs — What we did since the last updated session log, what we discovered, what’s next, to do items

Since Claude Code can nearly instantaneously sweep through the project and find all .md files, consume them, and “understand”, this process more or less ensures that functionally speaking institutional memory will persist even though Claude’s memory itself does not.

So, when I start a new session, I always tell Claude to read the markdown files first. It’s not a bad habit to have in general too because then you and Claude can both get back on the same page as that process can also help you remember where you left things off. And once it does that, it now knows the context, the previous decisions we’ve made, and where we left off.

The Socratic Approach

Claude is more or less like a reasonably trained Labrador retriever. But it can rush ahead, off its leash, and even though it will come back, it can get into trouble in the meantime.

So, to try and reign that in, I constantly ask Claude to explain its understanding back to me:

“Do you see the issue with this specification?”

“That’s not it. The problem is the standard errors.”

“Guess at what I’m about to ask you to do.”

This isn’t about testing Claude. It’s about ensuring alignment. I do not like when Claude Code gets ahead of me, and starts doing things before I’m ready. Part of this is because it is still time consuming to undo what it just did, and so I just want to try and control Claude as much as I can, and getting into Socratic styles of questioning it can help do that. Plus, I find that this kind of dialoguing helps me — it’s helpful for me to be constantly bouncing ideas back and forth.

When I ask it to guess where I’m going with something, I sort of get a feel for when we are in lock step or if Claude is just feigning it. If Claude guesses wrong, that reveals a misunderstanding that needs correcting before we proceed. In research, a wrong turn doesn’t just waste time—it can lead to incorrect conclusions in a published paper. This iteration back and forth I hope can temper that.

Verification Through Visualization

I never trust numbers alone. I constantly ask for figures:

“Make a figure showing this relationship”

“Put it in a slide so I can see it”

A table that says “ATT = -0.73” is easy to accept uncritically. A visualization that shows the wrong pattern makes the error visible. Trust pictures over numbers. So since making “beautiful figures” takes no time anymore with Claude Code, I ask for a variety of pictures now all the time. Things that aren’t for publication too — I’m just trying to figure out computationally what I’m looking at, how those numbers are even possible to compute, and spotting errors immediately.

MixtapeTools: The Repository

So, I’ve started collecting my tools and templates in a public repo: MixtapeTools. And here’s what’s there and how to use it:

The Workflow Document

Start with workflow.md. This is a detailed explanation of everything I just described—the thinking partner philosophy, external memory via markdown, session startup routines, cross-software validation, and more.

There’s also a 24-slide deck (presentations/examples/workflow_deck/) that presents these ideas visually. I try to emphasize to Claude Code to make “beautiful decks” in the hopes that it is sufficiently educated about what a beautiful deck of quantitative stuff is that I don’t have to write some detailed thing about it. The irony is that now that Claude Code can spin up a deck fast, with all the functionality of beamer, Tikz, ggplot and so on, then I am making decks for me — not just for others. And so I am consuming my work via decks, almost like I would be if I was taking notes in a notepad of what I’m doing. Plus, I am drawn to narrative and visualization, so decks also aid me in that sense.

CLAUDE.md Template

The claude/ folder contains a template for CLAUDE.md—the file that gives Claude persistent memory within a project. Copy it to your project root and fill in the specifics. Claude Code automatically reads files named CLAUDE.md, so every session starts with context.

Presentations (The Rhetoric of Decks)

The presentations/ folder contains my philosophy of slide design. I’m still developing this—it’s a bit of a hodge podge of ideas at the moment, and the essay I’ve been writing is overwritten at the moment. Plus, I keep learning more about rhetoric and getting feedback from Claude using its own understanding of successful and unsuccessful decks. So this is still just a hot mess of a bunch of jumbled ideas.

But the idea of the rhetoric of decks is itself pretty basic I think: slides are sequential visual persuasion. Beauty coaxes out people’s attention and attention is a necessary condition for enabled communication between me and them (or me and my coauthors, or me and my future self).

Like every good economist, I believe in constrained optimization and first order conditions, which means I think that every slide in a deck should have the same marginal benefit to marginal cost ratio (what I call “MB/MC equivalence”). This means that the marginal value of the information in that slide is offset by the difficulty of reading it and that anything that is truly difficult to read must therefore be extremely valuable.

This leads to trying to find ways to reduce the cognitive density in a slide. And it takes seriously that you are going to need to regularly remind people of the plot because of the innate distractedness that permeates every talk, no matter who is in the audience, because of the ubiquity of phones and social media. And so you have to find a way to remind people of the plot of your talk while maintaining that MB/MC equivalence across slides. Easy places to do that are titles. Titles should be assertions (”Treatment increased distance by 61 miles”), not labels (”Results”), because you must assume that the audience missed what the study is about and therefore doesn’t know what these results are for. And try to find the structure hiding in your list rather than simply listing with bullets if you can.

There’s a condensed guide (rhetoric_of_decks.md), a longer essay exploring the intellectual history (rhetoric_of_decks_full_essay.md), and a deck explaining the rhetoric of decks (examples/rhetoric_of_decks/) (meta!).

I’m working on a longer essay about this. For now, this is what I have.

Referee 2: The Real Innovation

This is what I think researchers will find most useful.

The problem: If you ask Claude to review its own code, you’re asking a student to grade their own exam. Claude will rationalize its choices rather than challenge them. True adversarial review requires separation.

The solution: The Referee 2 protocol.

How It Works

Do your analysis in your main Claude session. You’re the “author” in this scenario I’m going to describe. Once you’ve reached a stopping point, then …

Open a new terminal. This is essential—fresh context, no prior commitments. Think of this as a separate Claude Code in the same directory, but remember — Claude has no institutional memory, and so this new one is basically a clone, but it’s a clone with the same abilities but without the memory. Then …

Paste the Referee 2 protocol (from

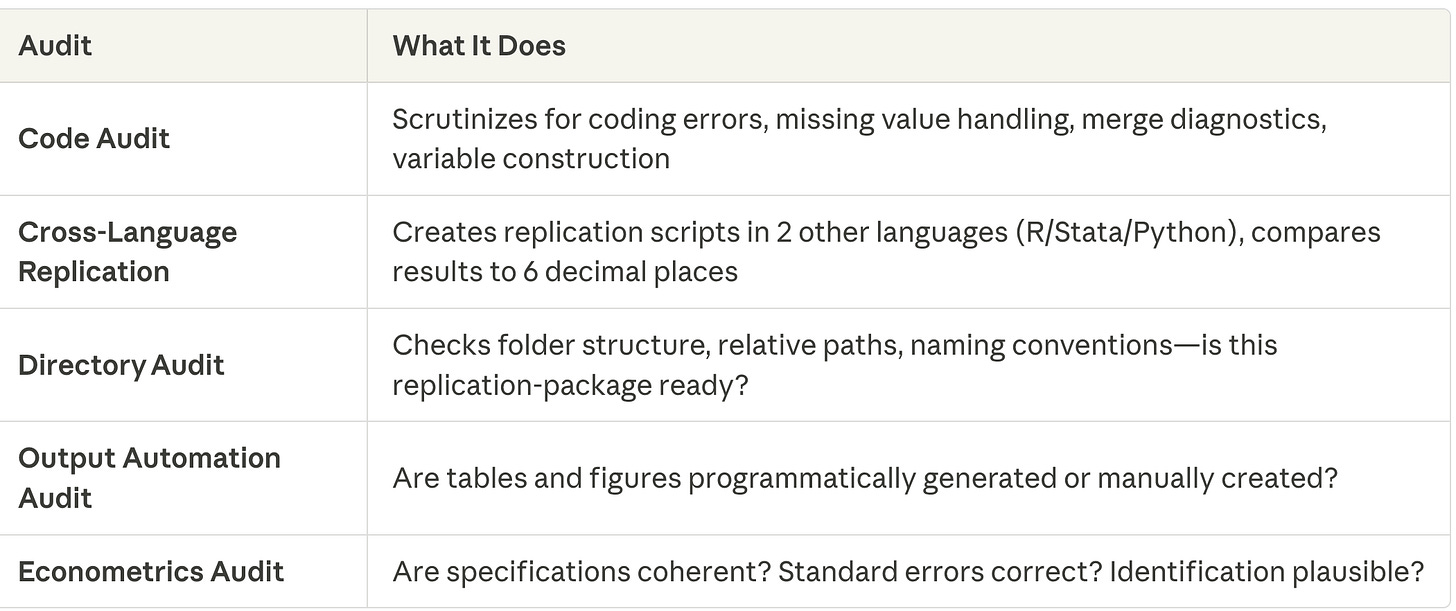

personas/referee2.md) and point it at your project.Referee 2 performs five audits:

Referee 2 files a formal referee report in

correspondence/referee2/, complete with Major Concerns, Minor Concerns, and Questions for Authors.You (i.e., the author) respond. For each concern: fix your code OR write a justification for not fixing. You record what you’ve done, as well as making the changes, and then …

Resubmit. Open another new terminal, paste Referee 2 again, say “This is Round 2.” Iterate until the verdict is Accept.

Why Cross-Language Replication?

This is the key idea behind why I’m doing this is a belief of mine that hallucination is akin to measurement error and that the DGP for those errors are orthogonal across languages.

If Claude writes R code with a subtle bug, the Stata version will likely have a different bug or not at all. The bugs are not likely correlated as they come from different syntax, different default behaviors, different implementation paths and different contexts.

But when R, Stata, and Python produce identical results to 6+ decimal places, you have high confidence that at minimum the intended code is working. It may still be flawed reasoning, but it won’t be flawed code. And when they don’t match, you’ve caught a bug that single-language review would miss.

The Critical Rule

Referee 2 NEVER modifies author code.

This is essential. Referee 2 creates its own replication scripts in code/replication/. It never touches the author’s code in code/R/ or code/stata/. The audit must be independent. If Referee 2 could edit your code, it would no longer be an external check—it would be the same Claude that wrote the code in the first place.

Only the author modifies the author’s code.

What Referee 2 Catches

In practice, the hops is that this process of revise-and-resubmit with referee 2 catches:

Unstated assumptions: “Did you actually verify X, or just assume it?”

Alternative explanations: “Could the pattern come from something else?”

Documentation gaps: “Where does it explicitly say this?”

Logical leaps: “You concluded A, but the evidence only supports B”

Missing verification steps: “Have you actually checked the raw data?”

Broken packages or broken code: Why are csdid in Stata and did in R producing different values for the simple ATT when the technique for producing those points estimates has no randomness to it? That question has an answer, and referee 2 will identify the problem and hopefully you can then get to an answer.

Referee 2 isn’t about being negative. It’s about earning confidence. A conclusion that survives rigorous challenge is stronger than one that was never questioned.

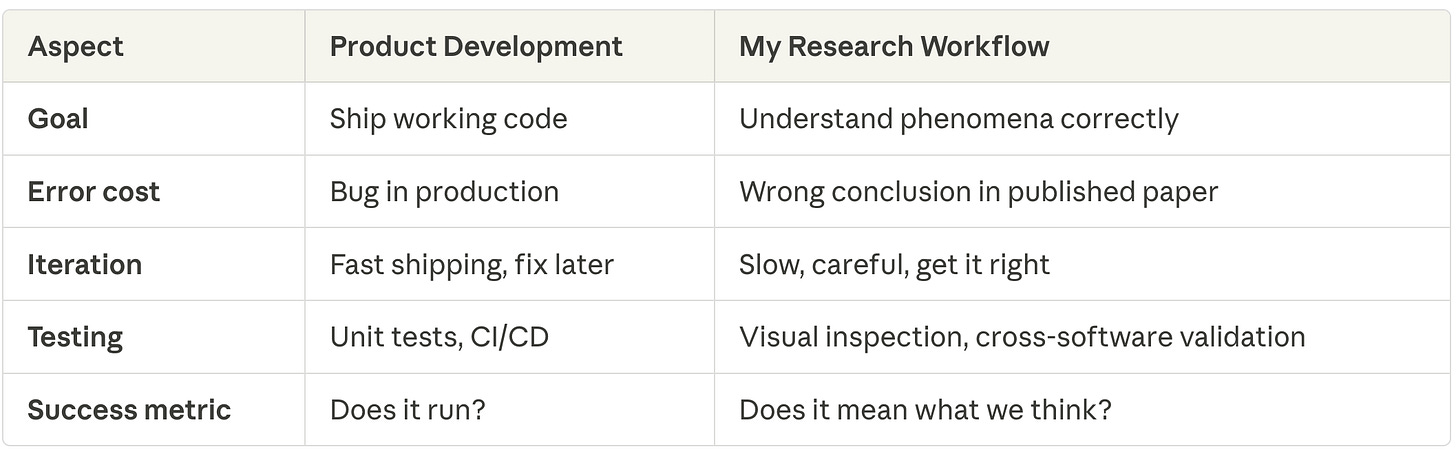

Research Is Not Product Development

Recall the theme of my broader series on Claude Code — the modal quantitative social scientist is probably not the target audience of the modal Claude Code explainer, who’s more likely a software engineer or computer scientist. So, I want to emphasize how different my workflow is from what I might characterize as a more typical one in software development:

A product developer might see code working and move on. But if I see results that are “almost right”, I cannot proceed at all until I figure out why it is not exactly the same. And that is because “almost right” almost always means a mistake somewhere and those have to be caught earlier, not later.

Work in Progress

The repo will grow as I continue to formalize more of my workflow. But right now it has:

The workflow philosophy and deck

The Referee 2 protocol

The rhetoric of decks materials

CLAUDE.md templates

More will come as I develop them.

Take everything with a grain of salt. These are workflows that work for me. Your mileage may vary.