Claude Code Part 14: I Asked Claude to Replicate a PNAS Paper Using OpenAI's Batch API. Here's What Happened (Part 1)

A case study in pushing Claude Code to do something genuinely hard

I’ve been experimenting with Claude Code for months now, using it for everything from writing lecture slides to debugging R scripts to managing my chaotic academic life. But most of those tasks, if I’m being honest, are things I could do myself. They’re just faster with Claude.

Last week I decided to try something different. I wanted to see if Claude could help me do something I genuinely didn’t know how to do: pull in a replication package from a published paper, run NLP classification on 300,000 text records using OpenAI’s Batch API, and compare the results to the original findings.

This is Part 1 of that story. Part 2 will have the results—but I’m writing this before the batch job finishes, so we’re all in suspense together. Here’s the video walk through. I’ll post the second once this is done and we’ll check it together.

Thank you again for all your support! These Claude Costs, and the substack more generally, are labors of love. Please consider becoming a paying subscriber! It’s $5/month, $50/year or founding member prices of $250! For which I can give you complete and total consciousness on your death bed in return.

The Paper: 140 Years of Immigration Rhetoric

The paper I chose was Card, et al. (PNAS 2022): “Computational analysis of 140 years of US political speeches reveals more positive but increasingly polarized framing of immigration.” Let me dive in and tell you about it. If you haven’t read it, the headline findings are striking:

Overall sentiment toward immigration is MORE positive today than a century ago. The shift happened between WWII and the 1965 Immigration Act.

But the parties have polarized dramatically. Democrats now use unprecedentedly positive language about immigrants. Republicans use language as negative as the average legislator during the 1920s quota era.

The authors classified ~200,000 congressional speeches and ~5,000 presidential communications using a RoBERTa model fine-tuned on human annotations. Each speech segment was labeled as PRO-IMMIGRATION, ANTI-IMMIGRATION, or NEUTRAL. But my question was can we update this paper using a modern large language model to do the classification? And can we do it live without me doing anything other than dictating to Claude Code the task?

If the answer to this question is yes, then it means researchers can use off-the-shelf LLMs for text classification at scale—cheaper and faster than training custom models—and for many of us, that’s a great lesson to learn. But I think this exercise also doubles to show that even if you feel intimidated by such a task, you shouldn’t, because I basically do this entire thing by typing my instructions in, and letting Claude Code do the entire thing, including finding the replication package, unzipping and extracting the speeches!

If no, we learn something about where human-annotated training data still matters. And we learn maybe that this use of Claude Code to do all this via “dictation” is maybe also not all it’s cracked up to be.

The Challenge: This Is Actually Hard

Let me be clear about what makes this difficult:

Scale. We’re talking about 304,995 speech segments. You can’t just paste these into ChatGPT one at a time.

Infrastructure. OpenAI’s Batch API is the right tool for this—it’s 50% cheaper than real-time API calls and can handle massive jobs. But setting it up requires understanding file formats, authentication, job submission, result parsing, and error handling.

Methodology. Even if you get the API working, you need to think carefully about prompt design, label normalization, and how to compare your results to the original paper’s.

Coordination. The replication data lives on GitHub. The API key lives somewhere secure. The code needs to be modular and well-documented. The results need to be interpretable.

I wanted to see if Claude Code could handle the whole pipeline—from downloading the data to submitting the batch job—while I watched and asked questions.

Step 1: Setting Up the Project

I started by telling Claude what I wanted to do using something called “plan mode”. Plan mode is a button you pull down on the desktop app. I have a long back and forth with Claude Code about what I want done, he works it out, I review it, and then we’re ready, I agree and he does it. If nothing else, watching the video, and skipping to plan mode, you can see what I did.

So what I did was I stored the paper myself locally (as I had a feeling he might not could get into the PNAS button thing to get it but who knows), then explained exactly what I wanted done. But what I did was I explained my request backwards. That is I told him what I wanted at the very end, which was a classification of the speeches the authors had but using OpenAI batch requested classification with the gpt-4o-mini LLM. And then I worked backwards from there and said I wanted an explainer deck, I wanted an audit using referee2 before he ran it, I wanted a split pdf using my pdf-splitter skill at my repo, and so forth. It’s easier to explain if you watch it.

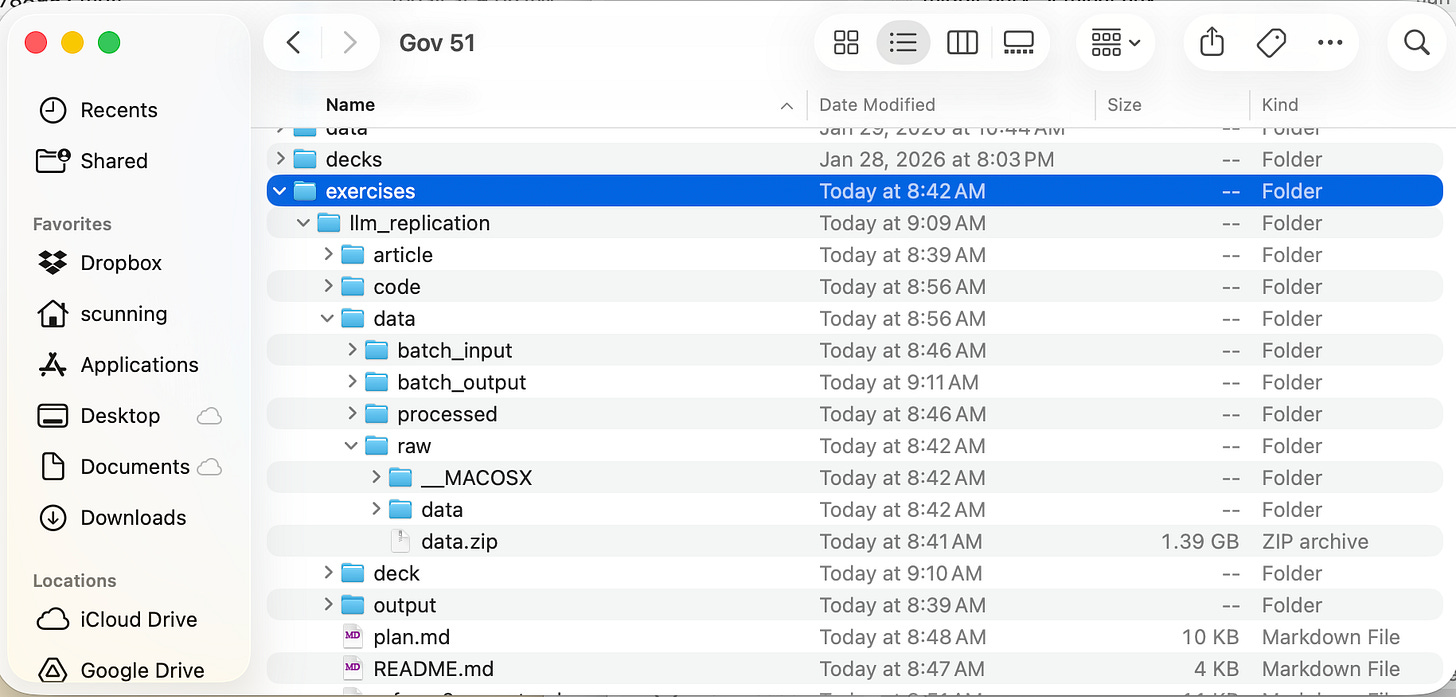

So once we agreed, and after some tweaking things in plan mode,Claude immediately did something I appreciated: it created a self-contained project folder rather than scattering files across my existing course directory.

exercises/llm_replication/

├── article/

│ └── splits/ # PDF chunks + notes

├── code/

│ ├── 01_prepare_data.py

│ ├── 02_create_batch.py

│ ├── 03_submit_batch.py

│ ├── 04_download_results.py

│ └── 05_compare_results.py

├── data/

│ ├── raw/ # Downloaded replication data

│ ├── processed/ # Cleaned CSV

│ ├── batch_input/ # JSONL files for API

│ └── batch_output/ # Results

├── deck/

│ └── deck.md # Presentation slides

├── plan.md

└── README.md

This structure made sense to me. Each script does one thing. The data flows from raw → processed → batch_input → batch_output → results. If something breaks, you know where to look. So this is more or less replicable and I can use this to show my students next week when we review the paper and replicate it more or less using an LLM, not the methodology that they used.

Step 2: Understanding the Data

The replication package from Card et al. is 1.39 GB. How do I know that? Because Claude Code searched and found it. He found it, pulled the zipped file into my local directory, and saw that using whatever tool it is in the terminal that lets you check the file size. Here’s where he put it.

The zipped file he then unzipped and placed in that ./data directory. It includes the speech texts, the RoBERTa model predictions, and the original human annotations. So this is now the PNAS, from the ground up.

When Claude downloaded the data and explored the structure, here’s what we learned:

Congressional speeches: 290,800 segments in a

.jsonlistfilePresidential communications: 14,195 segments in a separate file

Each record includes: text, date, speaker, party, chamber, and the original model’s probability scores for each label

It’s a little different than what the PNAS says interestingly which said there are 200,000 congressional speeches and 5,000 presidential communications. This came out to 305,000. So I look forward to digging more into that.

I also have the original paper’s classifier outputs probabilities for all three classes. If a speech has probabilities (anti=0.6, neutral=0.3, pro=0.1), we take the argmax: ANTI-IMMIGRATION. This was from their own analysis.

But Claude wrote 01_prepare_data.py to load both files, extract the relevant fields, compute the argmax labels, and save everything to a clean CSV. Running it produced:

Total records: 304,995

--- Original Label Distribution ---

ANTI-IMMIGRATION: 48,234 (15.8%)

NEUTRAL: 171,847 (56.3%)

PRO-IMMIGRATION: 84,914 (27.8%)

Most speeches are neutral—which makes sense. A lot of congressional speech is procedural.

Or are they neutral? That’s what we are going to find out. When we have the LLM do the classification, we are going to see if maybe there is still more cash on the table. And then we will create a transition matrix to see what the LLM classified as ANP and what the original authors classified as ANP. We’ll see if some things are getting shifted around.

Step 3: The Classification Prompt

This is where it gets interesting. How do you tell gpt-4o-mini to classify political speeches the same way a fine-tuned RoBERTa model did?

Claude’s first draft was detailed—maybe too detailed:

You are a research assistant analyzing political speeches about immigration...

Classification categories:

1. PRO-IMMIGRATION

- Valuing immigrants and their contributions

- Favoring less restricted immigration policies

- Emphasizing humanitarian concerns, family unity, cultural contributions

- Using positive frames like "hardworking," "contributions," "families"

2. ANTI-IMMIGRATION

- Opposing immigration or favoring more restrictions

- Emphasizing threats, crime, illegality, or economic competition

- Using negative frames like "illegal," "criminals," "flood," "invasion"

...

I had a concern: by listing specific keywords, were we biasing the model toward pattern-matching rather than semantic understanding?

This is exactly the kind of methodological question that matters in research. If you tell the model “speeches with the word ‘flood’ are anti-immigration,” you’re not really testing whether it understands tone—you’re testing whether it can grep.

We decided to keep the detailed prompt for now but flagged it as something to revisit. A simpler prompt might actually perform better for a replication study, where you want the LLM’s independent judgment. But, what I think I’ll do is a part 3 where we do resubmit with a new prompt that doesn’t lead the llm as much as I did, but I think it’s still useful just to see even using the original prompting, whether this more advanced llm, which has a lot more skill at discerning context than earlier ones (even Roberta), might come to the same or different conclusions.

Step 4: Creating the Batch Files

So now we get into the OpenAI part. I fully understand that this part is a mystery to many people. Just what am I exactly going to be practical doing in this fourth step? And that’s where I think relying Claude Code for help in answering your questions, as well as learning how to do it, and then using referee2 to audit the code, is going to be helpful. But here’s the gist.

To get the classification of the speeches done, we have to upload these speeches to OpenAI. But OpenAI’s Batch API expects something called JSONL files where each line is a complete API request. So, without me even explaining how to do it, Claude wrote 02_create_batch.py to generate these.

A few technical details that matter:

Chunking: We split the 304,995 records into 39 batch files of 8,000 records each. This keeps file sizes manageable.

Truncation: Some speeches are very long. We truncate at 3,000 characters to fit within context limits. Claude added logging to track how many records get truncated.

Cost estimation: Before creating anything, the script estimates the total cost:

--- Estimated Cost (gpt-4o-mini with Batch API) ---

Input tokens: 140,373,889 (~$10.53)

Output tokens: 1,524,975 (~$0.46)

TOTAL ESTIMATED COST: $10.99

Less than eleven dollars to classify 300,000 speeches! That’s remarkable. A few years ago, this would have required training your own model or paying for expensive human annotation. But now for $11 and what is going to take a mere 24 hours I — a one man show, doing all of this inside of an hour over a video — got this submitted! Un. Real.

Step 5: The Submission Script

03_submit_batch.py is where money gets spent, so Claude built in several safety features:

A

--dry-runflag that shows what would be submitted without actually submittingAn explicit confirmation prompt that requires typing “yes” before proceeding

Retry logic with exponential backoff for handling API errors

Tracking files that save batch IDs so you can check status later

I appreciated the defensive programming. When you’re about to spend money on an API call, you want to be sure you’re doing what you intend.

Step 6: Bringing In Referee 2

Here’s where things got meta.

I have a system I mentioned the other day called personas. And the one persona I have so far is an aggressive “auditor” called “Referee 2”—I use him by opening a separate Claude instance, so that I don’t have Claude Code reviewing its own code. This second Claude Code instance is referee 2. It did not write the code we are using to submit the batch requests. It’s sole job is to review the other Claude Code’s code with the critical eye of an academic reviewer and then write a referee report. The idea is to catch problems before you run expensive jobs or publish embarrassing mistakes.

So, I asked Referee 2 to audit the entire project: the code, the methodology, and the presentation deck. And you can see me in the video doing this. The report came back with a recommendation of “Minor Revision Before Submission”—academic speak for “this is good but fix a few things first.” I got an R&R!

What Referee 2 Caught

Label normalization edge cases. The original code checked if “PRO” was in the response, but what if the model returns “NOT PRO-IMMIGRATION”? The string “PRO” is in there, but that’s clearly not a pro-immigration classification. Referee 2 suggested using

startswith()instead ofin, with exact matching as the first check.Missing metrics. Raw agreement rate doesn’t account for chance agreement. If both classifiers label 56% of speeches as NEUTRAL, they’ll agree on a lot of neutral speeches just by chance. Referee 2 recommended adding Cohen’s Kappa.

Temporal stratification. Speeches from 1880 use different language than speeches from 2020. Does gpt-4o-mini understand 19th-century political rhetoric as well as modern speech? Referee 2 suggested analyzing agreement rates separately for pre-1950 and post-1950 speeches.

The prompt design question. Referee 2 echoed my concern about the detailed prompt potentially biasing results toward keyword matching.

What Referee 2 Liked

Clean code structure with one script per task

Defensive programming in the submission script

Good logging throughout

The deck following “Rhetoric of Decks” principles (more on this below)

I implemented the required fixes. I had to pause at certain points the recording, but I think it probably took about 30 minutes. The code is now more robust than it would have been without the review.

Step 7: The Deck

One thing I’ve learned from teaching: if you can’t explain what you did in slides, you probably don’t fully understand it yourself.

I asked Claude to create a presentation deck explaining the project. But I gave it constraints: follow the “Rhetoric of Decks” philosophy I’ve been developing, which emphasizes:

One idea per slide

Beauty is function (no decoration without purpose)

The slide serves the spoken word (slides are anchors, not documents)

Narrative arc (Problem → Investigation → Resolution)

I am going to save the deck, though, for tomorrow when the results are finished so that we can all look at the deck together! Cliff hanger!

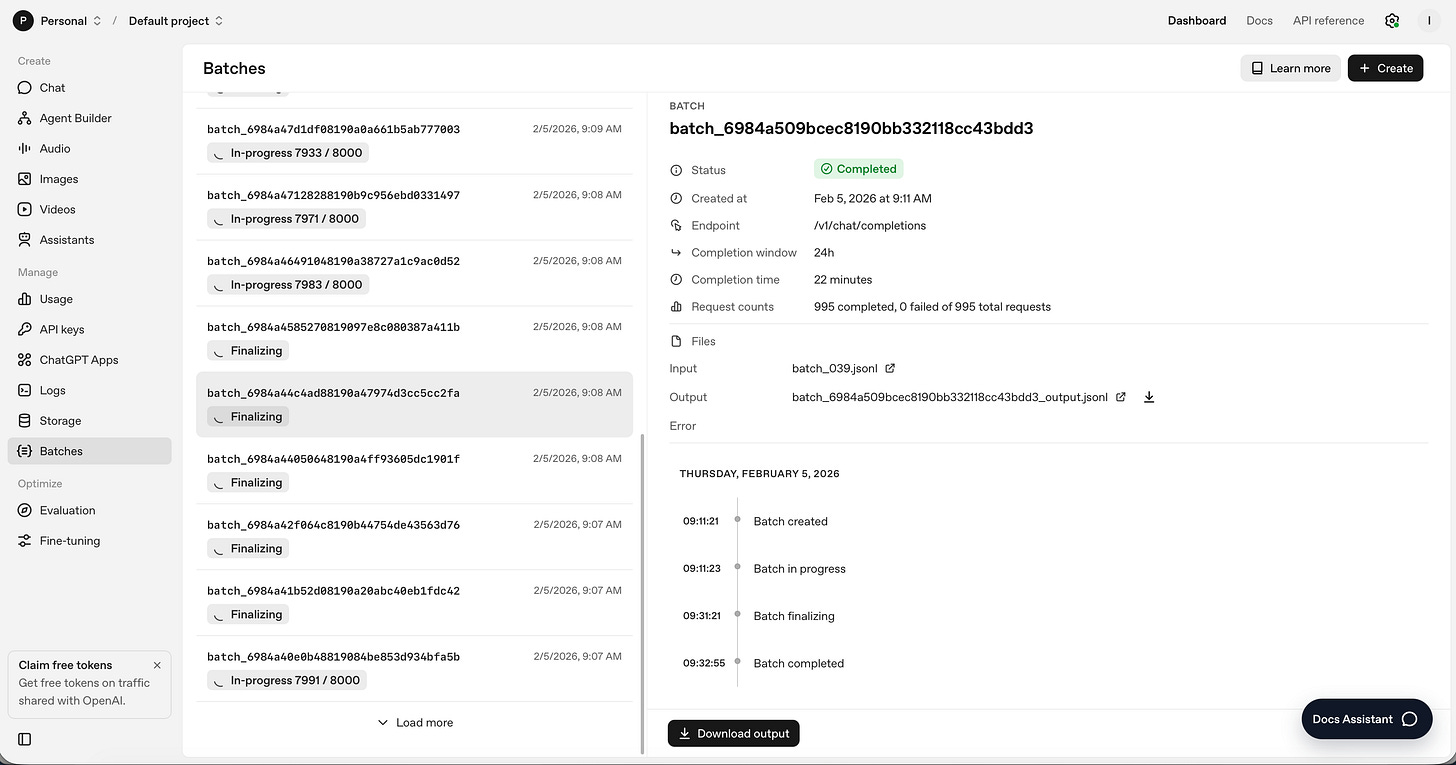

Where We Are Now

As of the moment of typing this, the batch has been sent. Here’s where we are at this moment. Some of them are nearly done, and some have yet to begin.

But here are some of the things I’m wondering as I wait.

Will the LLM agree with the fine-tuned model? The original paper reports ~65% accuracy for tone classification, with most errors between neutral and the extremes. If gpt-4o-mini achieves similar agreement, that’s a validation of zero-shot LLM classification. If it’s much lower, we learn that fine-tuning still matters.

Will agreement vary by time period? Will the LLM will do better on modern speeches (post-1965) than on 19th-century rhetoric? The training data for GPT models skews recent, or does it?

Will agreement vary by party? If the LLM systematically disagrees with RoBERTa on Republican speeches but not Democratic ones (or vice versa), that tells us something about how these models encode political language. I can do all this using a transition matrix table, which I’ll show you, to see how the classifications differ.

What will the disagreements look like? I’m genuinely curious to read examples where the two classifiers diverge. That’s often where you learn the most.

What This Experiment Is Really About

This started as a test of Claude Code’s capabilities. Can it handle a real research task with multiple moving parts? Can it handle a “hard task”?

The answer so far is yes—with caveats. Claude needed guidance on methodology. It benefited enormously from the Referee 2 review. And I had to stay engaged throughout, asking questions and pushing back on decisions. Notice this was not “here’s a job now go do it”. I am pretty engaged the whole time, but that’s also how I work. I suspect I will always be in the “dialogue a lot with Claude Code” camp.

But the workflow worked. We went from “I want to replicate this paper” to “batch job submitted” in about an hour. The code is clean and was double checked (audited) by referee 2. The documentation is thorough. The methodology is defensible. We’re updating a paper. I’m one guy in my pajamas filming this whole thing so you can just see for yourself how to use Claude Code to do a difficult task.

To me, the real mystery of Claude Code is why does the copy-paste method of coding seem to actually make me less attentive, but Claude Code for some reason keeps me more engaged, more attentive? I still don’t quite understand psychologically why that would be the case but I’ve noticed over and over that on projects using Claude Code, I don’t have the slippery grasp on what I’ve done, how I’ve done it, and so as I often did with the copy-paste method of using ChatGPT to code. That type of copy-paste is more or less mindless button pushing. Whereas I thinking how I use Claude Code is not like that, and therein lies the real value. Claude didn’t just do the work—it did the work in a way that taught me what was happening. I think that at least for now is labor productivity enhancing. I’m doing new tasks I couldn’t do, I’m getting to answers I can study faster, I’m thinking more, I’m staying engaged, and interestingly, I bet you I’m spending the same amount of time on research, but less time on the stuff that isn’t actually “real research”.

Coming in Part 2

The batch job will take up to 24 hours to complete. Once it’s done, I’ll download the results and run the comparison analysis.

Part 2 will cover:

Overall agreement rate and Cohen’s Kappa

The transition matrix (which labels does the LLM get “wrong”?)

Agreement by time period, party, and source

Examples of interesting disagreements

What this means for researchers considering LLM-based text classification

Until then, I’m staring at a tracking file with 39 batch IDs and waiting.

Stay tuned.

Technical details for the curious:

Model: gpt-4o-mini

Records: 304,995

Estimated cost: $10.99 (with 50% batch discount)

Classification labels: PRO-IMMIGRATION, ANTI-IMMIGRATION, NEUTRAL

Comparison metric: Agreement rate + Cohen’s Kappa

Time stratification: Pre-1950 vs. Post-1950 (using Congress number as proxy)

Repository (original paper’s replication data):github.com/dallascard/us-immigration-speeches

Paper citation:

Card, D., Chang, S., Becker, C., Mendelsohn, J., Voigt, R., Boustan, L., Abramitzky, R., & Jurafsky, D. (2022). Computational analysis of 140 years of US political speeches reveals more positive but increasingly polarized framing of immigration. PNAS, 119(31), e2120510119.

You've mentioned before that so much of the materials on using tools like Claude Code is oriented towards software developers, and that's most of what I've read, and why I've subscribed to your Substack.

At around the 46-minute mark, you ask Referee 2 to review the work, but you don't create a fresh context window. I was surprised to see that, but perhaps you haven't found it to be a practical issue? That's something the software developers are always hyper-vigilant about, so I've just followed that advice when I have been able to play around with CC. But maybe I should just go yolo.

You mentioned powerpoint; I wonder if you can combine your "Rhetoric of Decks" skill with Anthropic's 'pptx' skill. https://github.com/anthropics/skills/tree/main/skills/pptx

This is genius, Scott. I've been trialling something myself recently with some qualitative research. What I found really helpful is to set up a Claude agent to effectively learn the methodology from a keystone paper or systematic review paper, and then save that and implement it across the project. Still tinkering, but it seems to be highly effective.