European Travels, Suicidality and Mental Illness in Jails, Workshop announcement

Plus an Inappropriate but Funny Joke from my Scottish Taxi Driver on the Way to Sterling

This substack is just an update about my travels in Europe, but it’s also doubling to tell others about two workshops this summer that I’m teaching aimed at the GMT+8 (Beijing, Tokyo, Australia) time zones. And if you read through, you can read a completely inappropriate joke that my taxi driver told me on the way to Sterling, which is just too hilarious not to share. But don’t shoot the messenger — he said it not me!

Greetings from Europe!

I arrived in Madrid one week ago to present seminars at UC3M followed by CUNEF on my new paper with Vivian Vigliotti, Karen Clay and Jonathan Seward, “Transitional Age in Jail: Mental Illness, Mental Health Classification, and Outcomes” though I wonder if we changed the title as the heading of my slides is called “Mental Illness Among Transitional Age Youth: Evidence from a Large Urban County Jail”. You can click on those hyperlinks if you want to read either the paper (first link) or read the slides (second link), but overall the response to the paper was great, which was encouraging. I think it was the best response to a paper of mine since I was on the road presenting my paper about the legalization of indoor sex work coauthored with Manisha Shah (click here) back in the day. I am slower in my output than most applied microeconomists, especially so ever since my book came out in January 2021. But I’ve presented this new project on suicide attempts, length of stay, recidivism and mental illness among inmates in jails (not prisons, but jails) several times now, and I think the presentations at UC3M and CUNEF were the best so far.

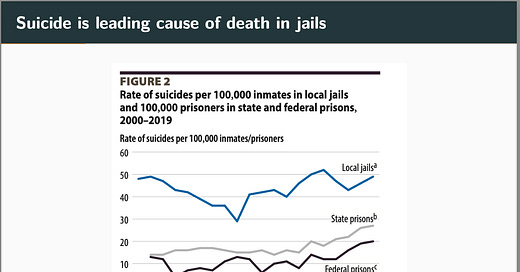

The paper uses a leniency design with randomized clinicians at booking after arrest to estimate the LATE parameter for those compliers who received a worse “daily functioning” score. Daily functioning is our proxy for the severity of mental illness that clinicians scores at booking during a 15 to 30 min evaluation mandated by the state. The paper is a bit of a mystery, and you’ll have to read it to see why we say that, but here are some interesting pictures to help motivate why we are working on this topic:

Suicide is leading cause of death in jails at a rate of 49 per 100,000 inmates (compared to 14.2 per 100,000 in the general population and 46 per 100,000 among post 9/11 vets). For some subpopulations within jails, the suicide rate is much higher — for White males, for instance, it’s 86 suicides per 100,000. This is from recently published data by the BJS from 2021 about the 2019 rates. When COVID numbers come out, I suspect it will be so high that the press will begin to cover it more intensively.

The backdrop of this from the sweep of the last 50 years is two things:

America’s grand experiment with incarcerating over 750,000 people in jails and 125,000 in prisons, bringing our total incarceration to 2 million and times over 2.2 million. We have the highest level of prisoners and inmates of any OECD country in the world, and the highest rate, by a large margin. Derek Neal argues this isn’t caused by the war on drugs but rather a more general “war on crime”, but whatever the cause, it’s high.

And at the time we embarked on this grand experiment, we were already a few years into another grand experiment — the defunding of publicly funded psychiatric hospitals. Here’s just one figure I found of the number of residents in residential psychiatric treatment beds at end of year from 1970 to 2014. As you can see, the US saw dramatic declines from the third quarter of the 20th century to now in the number of individuals in 24 hour residential treatment for mental illness. The hope that you’ll often find quoted in this literature is that a private community response was to occur, but it did not.

The causes of the decline in beds is complex — was it supply side, demand side or both. It was at least partly demand side no doubt — medical breakthroughs in the treatment of bipolar (e.g., lithium), depression (e.g., Prozac) and schizophrenia (e.g., various antipsychotics like clozapine) did allow individuals suffering from severe mental illness to not need residential care. But it’s also the case that the government did shift policy away from publicly funded residential care.

Involuntary hospitalization in particular became very difficult unless you met what’s called “criteria” which meant actively suicidal and actively homicidal. But of course by the time someone is actively either of those, it may be too late. And the adverb, “actively”, is doing a lot of work there. Actively does not mean homicidal or suicidal a week ago. It mean around the window of time at admission. And once a person is stable and no longer actively homicidal or suicidal, they will be released, back into the community where the environmental context of their life likely returns and they are no longer compliant with medication and may not have housing or support waiting for them. Many end up homeless, cycling in and out of emergency departments, dead or in jail, which causes the jail to become the mental hospitals of last resort. And that’s the context of our study.

We are focused not on mental illness and its cause on suicidality, time spent in jail and recidivism, but rather, classifications that someone’s mentally ill on suicidality, time spent in jail and recidivism. To understand the difference imagine a supply and demand curve — demand is associated with the unknown latent stock of mental health in a person, and the supply side is the classification or diagnoses of individuals by clinicians. In equilibrium each person is the mix of two things: some unknown stock of mental health and some known classification associated with some treatments. Ordinarily it is hard to disentangle the two, made particularly more problematic given in the general population individuals self select into working with therapists and doctors who then endogenously assign mental health classifications often used for billing purposes. This selection creates mirroring problems (Manski), much like peer effects, and so depending on the nature of that sorting, it is impossible without an RCT to disentangle the supply side from the demand side factors.

But in our jail, an RCT of sorts was run by the assignment of clinicians randomly to inmates within 36 hours of booking. We calculated the residualized leave-one-out mean daily functioning score (discretized into a high and low number to facilitate a LATE interpretation) for each clinician within a particular calendar date month window (i.e., February 2018, March 2018). We then regressed a person’s own binary score against their clinicians “leave one out mean” score and find a very high first stage with an Olea and Pfleuger effective F sometimes as high as 200 to 500. Not terribly uncommon, though, in situations where decision makers have wide discretion.

We estimate just identified 2SLS and IV LASSO models with clinician fixed effects, but the results don’t change a lot. Young with misdemeanors see an increase of 3.99 in suicide attempts, adults with misdemeanors 2pp and adults with felonies 1.8pp. We think this is being driven by two things: a proximate and an ultimate cause. The proximate cause we think is longer time spent in jail. Misdemeanors spend 7.5 additional days, and adults 50.3 additional days. But what’s the ultimate cause — that is, why are they spending longer time in jails? Oddly enough, it doesn’t seem that the jail uses the daily functioning score — the county does, later, after they leave jail, to sort them into mental health courts or traditional courts, but the jail is not aware of exactly how it even could be used since their decision making is based on a variety of clinical analysis done later. But we do know that this information does often make it back to caregivers and the judge, and anecdotally, it sounds like the information can result in either or both refusing to bail out and give bond out of concerns like homelessness. This can lead to longer length of stays. We then estimated the effect of suicide attempts per day in jail and found that the effect doesn’t appear to be merely mechanically a function of longer stays — the hazard also rose around 0.7pp per day spent in jail. So whatever is happening, jail appears to be very distressing for the marginal compliers. And after they leave, they’re around 20pp higher rates of reentering later due to another arrest.

So it was good to come to Madrid and share this information with the departments. I think they were very interested in both the institutional factors, but also the research, but even in America a lot of these basic facts are not well known.

Workshops in Europe and the US

But I also came to Europe to do a variety of workshops on causal inference. In Madrid, on Friday, I did an afternoon 3 hour workshop on differential timing called “Master Class” that was well attended and that I was told was great. That was a good shot in the arm. Today through Tuesday, I’m in Sterling Scotland doing a 3-day workshop on difference in differences and synthetic control. That too should be fun. And then later this week on Thursday and Friday I’m in London at Royal Holloway doing a two day workshop on diff in diff. Then I spend a couple days in London before flying back to do a one day workshop on unconfoundedness and synth as keynote at a conference at Microsoft.

And then I go home where my two daughters, my two inside cats (Betty and Ronnie) and three new strays that I finally decided to catch, take to the vet, and then adopt inside after watching predators pick off the patriarch and one of their sisters await for me. I hired a “cat whisperer” who has been meeting with them daily where they are now locked in my bedroom away from my bedroom.

Mixtape Sessions Summer workshops on causal inference

And last update — two new workshops this summer on causal inference. I’m doing Causal Inference I starting June 17th and Causal Inference II starting July 15. These are different than other workshops in that the time zones are aimed at GMT+8, which is I think the right lettering for Beijing (7am), Tokyo (8am) and Australia time zones. Demand for the workshops by students and faculty and other professionals in these time zones has been high, but the time zone differences are extreme, so I decided to muscle up and do another pair of workshops aimed just at this community.

Starting this fall, I will be teaching 3 causal inference workshops, not 2. The second will be just diff-in-diff so I can go at a little slower pace with more coding, and the third will just synthetic control so I can cover more material. And then we also have some old familiar faces and some new ones too who will be teaching more advanced courses based on classic designs as well as extensions in new areas that I think will be helpful.

Mixtape related material, like the substack, the workshops, the book and the podcast continues to be an exciting labor of love. I try to make it simple though - price discrimination over zoom allows me to teach those with low ability to pay at very low prices and those with higher ability to pay at still low relative prices compared to other workshops. I’m up to around 112 or so paying subscribers (the rest are comps I gave some supportive friends and family members who have been there for me through thick and thin). Those basically subsidize the podcast, so that’s been great.

And the podcast project has itself been great. This summer I have lined up new interviews with Pahkes and David Card, and have in the can already filmed a bunch more. My effort to “create an oral history of economics over the last 50 years through the personal stories of economists” has itself become a passion project of mine. I’m hoping that I can keep it up for another decade and have around 500 interviews which maybe do form an interesting patchwork quilt that someone else might find useful. But until then, I hope people find them just helpful for getting to know the real lives of economists who were once just like the rest of us because they are just now even just like each of us.

Future

I’m excited about some new things I’ve begun working on, too, but which I’m not yet at liberty to say. But one of them is CodeChella, and the other is something else. Fingers crossed they can both come together and be an opportunity to continue building community and helping people all over the world have an easier and more enjoyable time learning practical econometrics. “Econometrics for the people!” as Andrew Goodman-Bacon likes to say.

Thanks again for all your support. Once I get back from my travels, I will get back to writing my explainers on a semi-regular basis, as well as working on the revision of my book. Have a great week and weekend. And the inappropriate joke I now place behind the paywall!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Scott's Mixtape Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.