Mixtape Mailbag #8: Continuous Triple Differences

Kind of a longer post about the new Callaway, Goodman-Bacon and Sant'Anna revised continuous diff-in-diff paper

What a weekend. Two days of workshopping on causal inference, still haven’t put together the treadmill, and finished Mr. and Mrs. Smith on Amazon Prime. That show turned out to really speak to me. It’s about marriage, and challenges in it, but also about killing people for some kind of international spy organization. I’m giving in 5 out of 5 stars, as I mentioned on Saturday. But that’s neither here nor there. Today I am going to answer a friend’s email regarding the use of triple differences with continuous treatment. This is an email from TS.

Dear Scott

Is there something like a triple difference with continuous treatment? Or is it just as simple as replacing the treatment dummy with the continuous variable?

TS

Dear TS,

It’s always great to get an email from you. Let me tell you a little about what’s going on here so you can paint a picture. I have now moved into my new house. I haven’t fully emptied the old house out, but it’s probably 80% empty. I go there most mornings to feed the feral cats that I quasi-adopted, which raises my anxiety a lot because when I have missed a few days, I get the distinct impression they’ve not eaten. I really don’t have a good plan for how to help them out of the nest. I seriously consider bringing them here to my new house, but then I’d have five cats, and while I am now an empty nester to some degree, I’ve never had more than two cats in my life. Adopting the stray, Clara, and adding her to the mix already increased my cats to three — Betty, Ronnie and now Clara. If I were to bring Simba and Tigger in, it just seems like a lot of cats. The house could accommodate it according to ChatGPT-4, but I just don’t think my “main cats” — Betty and Ronnie — could handle it. I would give anything if I could solve this problem in a Pareto optimal way, but I’m not sure that exists anymore.

I also am stressed out a lot thinking about the fact that this summer, from to the third week of May to the first week of August I will be in Madrid, Turin, Scotland, Vietnam and Chicago. All summer. I cannot figure out what to do with Betty and Ronnie. Clara I can figure out, but it’s those two that are stressing me out as I worry they can’t handle being away from me for that long, and if I come back to two broken hearted cats who think I abandoned them, I just don’t know if I have the fortitude for more disappointment like that. So I went onto two subreddits this weekend — r/cats and r/travel — and just asked if anyone had ever actually traveled successfully to Europe for the summer with two cats. Not surprisingly, the first response I got was that it was crazy, don’t do it, but ChatGPT-4 (“Cosmos”) seems to think it’s doable so long as I do a ton of planning. I’m going to go see the veterinarian I think this week or the next and just pin down the logistics. If bank robbers can successfully plan an elaborate heist and get away with tens of millions in bearer bonds and gold, then I don’t see why I can’t get two cats to Spain, Italy, Scotland, and Vietnam. So I’m not quite yet ready to throw in the towel on this, but I’ll keep you informed.

But let’s cut to the chase. You ask whether the triple difference design can be used with a continuous treatment, and I wanted to use this as an opportunity to revisit a paper by Callaway, Goodman-Bacon and Sant’Anna on difference-in-differences and continuous treatments. After much harassment by yours truly to hurry up and revise the paper, the team finally did and you find it here. Amazingly, even though the paper is still in working paper form, it already has over 400 cites. Rumor has it the paper is now under review, though. So let’s begin.

First, this is a beautiful paper. I encourage you to read it and closely as I think you’ll really enjoy given your background in econometrics and, like me, your love of learning and growing. That team has really found their voice I think. You can see the signature marks of all three of them I think, although I hesitate to say why I think certain parts of the paper have origins in certain parts of the team as I don’t know with certainty. But knowing them, I wondered if the twoway fixed effects decomposition results almost certainly would be things that Andrew worked out early on. Almost certainly, all the historical easter eggs, like footnote 2, are Andrew’s, though. Only Andrew is going to find a 1965 quote from Sir Austin Bradford Hill for discussing the “dose-response curve”. Anyway, I really love this paper.

Before we dive into the triple differences portion, let’s first start out with the target parameter. What is the target parameter when treatment is continuous and how does it compare with the treatment parameters we were familiar with when treatment was binary?

Defining the Parameter when Treatment is Continuous

The paper showed up in July 2021, and the newest version is late January 2024. Originally the paper only had the decomposition results, as well as a detailed description of a parameter most likely associated with the continuous treatments. Recall that when working with binary treatments, we will be most likely estimating an average causal parameter. If it’s estimated with difference-in-differences, then it’s the average treatment effect on the treated group, or ATT. And that falls directly out of the binary treatment itself. Under parallel trends, no anticipation and SUTVA, the simple 2x2 difference-in-differences point identifies it, too.

But the issue comes — well, what about a non-binary treatment? What if the treatment isn’t a switch of 0 or 1, but rather, it’s a dosage. Every night I take melatonin gummies to help me sleep. Thank goodness the lethal dose of melatonin is probably non-existent or I would be dead, because whoever decided to put melatonin in these delicious gummies would’ve signed my death warrant. I basically pour the bottle upside down and eat them like I’m eating peanuts from the jar. I, in other words, am eating 30-50mg of melatonin at night (don’t judge). That is my dosage. But what is my comparison state? Is it 0mg melatonin? Is it 10mg melatonin? Is 100mg melatonin?

Point is, the causal parameters must be defined not just in terms of what the treatment status, but also what the comparison status is, and it must be exactly defined. We work so often with dummy variables that we get into the habit of thinking “this” and “not this”, but really we should be thinking of “this treatment dose” vs “this other treatment dose”, because the causal effects are always Y(1)-Y(0) and those are well defined states of the world.

The same goes here. The team dug back into an old paper by Angrist and Imbens from the 1990s — one of their many papers on instrumental variables from that productive time period. This paper was from JASA and had to do with “treatment intensity”, or what Callaway, Goodman-Bacon and Sant’Anna call the dose. The parameter of interest, cutting to the chase, with dosages isn’t the ATT, but rather it’s a new parameter maybe you haven’t seen called the “average causal response function”. Listen to their definition of the parameter:

“We call the difference between a unit’s potential outcome under dose d and its untreated potential outcome a level treatment effect. We call the difference in a unit’s potential outcome with a marginal increase in the dose a causal response (Angrist and Imbens, 1995). When treatment is binary, these two notions of treatment effects coincide, but they do not under a continuous treatment. Importantly, level treatment effects and causal responses can have meaningfully different interpretations, and we establish that they require different identifying assumptions as well.” (Callaway, Goodman-Bacon, and Sant’Anna 2024, p. 1)

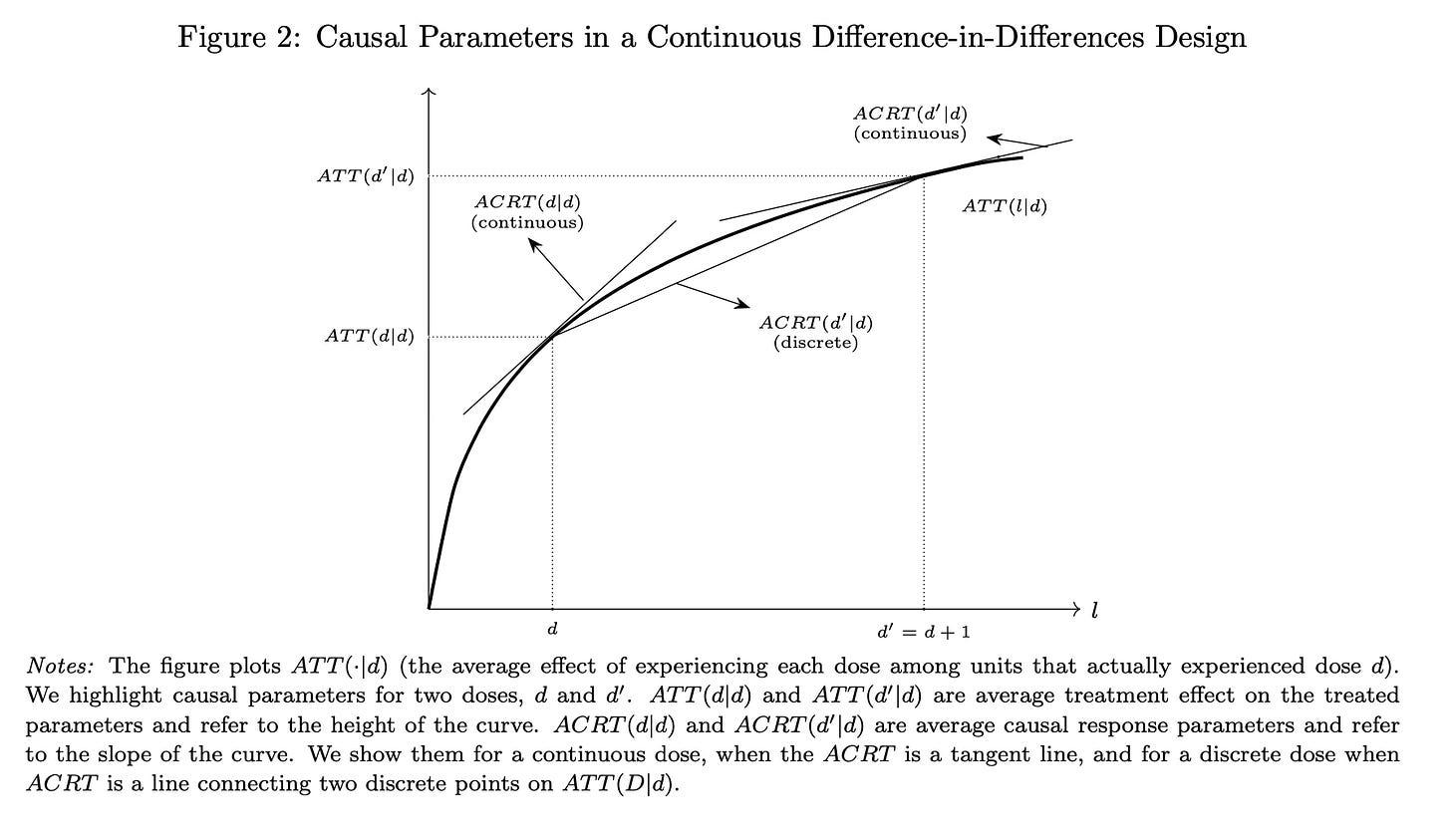

In some ways, for me anyway, the heart and soul of the paper is the careful defining of the parameters that would be associated with dose response function. As they say, when there is a binary treatment, then we are simply working with the difference between a particular dose d (e.g., 30mg of melatonin) and some untreated state (e.g., 0mg of melatonin), which would be the familiar treatment effect, or here “level treatment effect”. But when we are comparing two dosages — say melatonin at 30mg to melatonin to 15mg — then we are moving along a dosage curve. They give an example of this in Figure 2.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Scott's Mixtape Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.