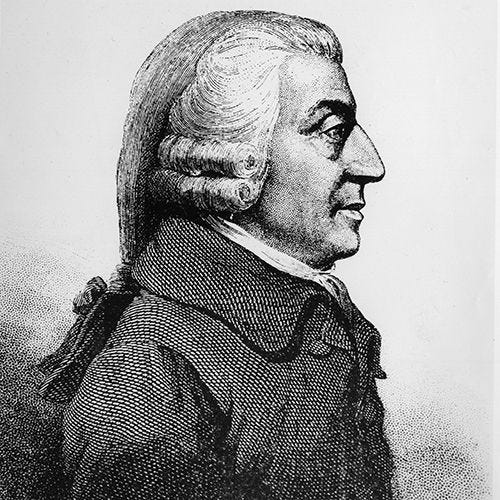

Podcast Interview with GPT4's Adam Smith

We discuss his new book, Wealth of Nations, growing up with a single mom, his friendship with David Hume, Daron Acemoglu and advice for aspiring economists

Opener to Podcast Interview with GPT4’s Adam Smith

Welcome to the Mixtape with Scott, a podcast that provides an oral history of economics, covering topics spanning the last 50 years (though today I relax that constraint a little bit). I focus on subjects I personally find interesting and important, from personal preferences like Becker's students to contemporary topics like economists in tech. But this is also a platform to explore personal stories of real economists as they walk us through their lives from childhood to present and share the biographies of some of their work. While it’s debatable that today’s guest is real, I'm nonetheless real and your host, Scott Cunningham!

This week, I had the unique opportunity to interview GPT-4's Adam Smith, not the real Adam Smith, but an AI representation of him, and specifically the 1778 Adam Smith who had published his magnum opus, Wealth of Nations, just two years earlier. Nonetheless, it was a sincere conversation where I, as the host, delved into various aspects of his life and ideas. We discussed a range of topics, from growing up with a single mother, to his friendship with David Hume, to his two major works, Theory of Moral Sentiments and Wealth of Nations, to Daron Acemoglu, advice to aspiring economists and much much more.

Despite being an AI representation, our conversation provided fascinating insights into the life and thoughts of one of the most influential economists in history. Join us as we explore the personal story of GPT-4's Adam Smith and discuss the impact of his work on economics as a discipline. And as this part of the GPT-4 Explains Econometrics series, it’s partly behind a paywall. But I’ll leave enough of a teaser for you to go back in time and hear from a large language model predicting Adam Smith’s response to my questions and our conversation.

Thank you for tuning in again, and don't forget to like, share, and subscribe to the podcast. Also, check out my Substack, "Scott's Substack," where I semi-regularly post what I call "explainers" about econometrics.

Transcript

Welcome to the podcast, everyone! Today, we have a very special guest with us. He's the author of "An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations," a foundational work in the field of economics published just two years ago in 1776. Please join me in giving a warm welcome to the brilliant thinker and philosopher, Adam Smith. Welcome to the show, Adam!

[Adam Smith]: Thank you for having me on your podcast. It's a pleasure to be here and share my thoughts with your audience.

Now, for the sake of our listeners who may not be familiar with you, could you please tell us your name, your title at work, and who your boss is?

[Adam Smith]: Of course. My name is Adam Smith, and I am a moral philosopher and political economist. At the moment, two years after the publication of "The Wealth of Nations," I am serving as a Commissioner of Customs in Scotland. In this role, I report to the Board of Customs, which is responsible for overseeing the collection of customs and excise duties in the country. Previously, I held the position of Chair of Moral Philosophy at the University of Glasgow, where my focus was on educating students and advancing the study of moral philosophy.

I can't wait to dive into your decision to leave academia and go into administration in Scotland government. But before we do, I want to start with an icebreaker. If you could travel to any time period, where and when would you go, and why?

[Adam Smith]: That's an intriguing question. If I had the ability to travel through time, I would be quite interested in visiting the future, perhaps a century or two from now. The reason for this choice is my curiosity about the progress of society, both in terms of economic development and moral understanding. I would like to observe how the principles I have explored in "The Wealth of Nations" and "The Theory of Moral Sentiments" have evolved over time, and how societies have adapted and applied these ideas to further enhance the well-being and prosperity of their citizens. It would be a remarkable opportunity to witness the advancement of human knowledge and the improvement of living standards.

I say, "I would absolutely love to travel with you into that future too. I think we would both find that trip absolutely mind blowing. I'd like to start now with your childhood. Can you tell us about where you grew up and what your childhood was like?"

[Adam Smith]: Certainly. I grew up in the small town of Kirkcaldy, in Fife, Scotland. I was born on June 16, 1723, and unfortunately, my father passed away a few months before my birth. My mother, Margaret Douglas, raised me as a single parent, and she played a significant role in my life, providing a nurturing environment for my education and personal growth.

As a child, I was rather quiet and studious. I had a keen interest in learning and spent much of my time reading and exploring various subjects. My mother's encouragement and support allowed me to pursue my intellectual interests from a young age.

I attended the local school in Kirkcaldy before moving on to the University of Glasgow, where I studied moral philosophy under the tutelage of Francis Hutcheson. My time at the university greatly shaped my intellectual development, and it was there that I began to delve deeper into the realms of philosophy, economics, and morality, which would later become the focus of my life's work.

I say, "I'm sorry. I didn't know that about your father. That must have been hard on your mother. How old was he when he died? And how old was your mother? Did your mother ever share the cause of his death with you?"

[Adam Smith]: My father, also named Adam Smith, was born in 1679, making him 44 years old at the time of his death. My mother, Margaret Douglas, was born in 1697, so she was around 26 years old when my father passed away. As for the cause of his death, it was not something that was discussed at length during my childhood, but I understood that he passed away due to an illness.

Despite the challenges she faced as a young widow, my mother remained a strong and supportive figure throughout my life. She focused on providing a stable and nurturing environment for me, which enabled me to pursue my academic interests and intellectual growth. Her unwavering support has been instrumental in my personal and professional development.

I say, "She sounds amazing. It sounds like you and her were close then. I may ask more questions about your family, but first, Were there any subjects or hobbies that you were particularly passionate about as a child?"

[Adam Smith]: Yes, my mother and I shared a close bond, and her influence has been invaluable throughout my life. As a child, I was particularly passionate about learning and reading. My curiosity led me to explore various subjects, including history, literature, and philosophy.

My interest in philosophy eventually guided me towards the study of moral philosophy and political economy. These subjects became the foundation of my life's work, as they allowed me to examine human behavior, social structures, and the factors that contribute to the prosperity of nations.

Aside from my academic pursuits, I also enjoyed engaging in intellectual discussions with friends and acquaintances. These conversations often revolved around the philosophical and economic ideas that I was studying, and they played a crucial role in the development of my own thoughts and theories.

Although I was not particularly athletic, I found pleasure in taking long walks, which provided me with the opportunity to reflect on my ideas and observations. These walks not only kept me physically active but also contributed to my intellectual growth and the formation of my philosophical and economic theories.

I say, "Growing up without your father must have shaped the kinds of relationships you developed with adults. Outside of your mother, Did you have any role models or inspirations growing up?"

[Adam Smith]: Indeed, growing up without my father did have an impact on the relationships I formed with other adults. In addition to my mother, there were several individuals who played influential roles in my intellectual development.

One such person was Francis Hutcheson, my professor of moral philosophy at the University of Glasgow. Hutcheson's teachings and ideas had a profound effect on me, helping to shape my thoughts on ethics, human nature, and the principles of social order.

Another significant figure was David Hume, a fellow Scottish philosopher and a close friend of mine. Hume's work on empiricism, skepticism, and the nature of human understanding greatly influenced my own thinking and the broader field of philosophy. Our friendship and the intellectual exchanges we shared contributed to the development of my ideas, particularly in the areas of moral philosophy and political economy.

These individuals, along with others I encountered during my education and early career, served as sources of inspiration and guidance, helping to mold my understanding of the world and my approach to the study of human behavior and society.

I say, "I knew about Mr. Hume's influence on you. I've heard you also had an influence on him too. How did the two of you first meet?"

[Adam Smith]: David Hume and I first met in the early 1750s in Edinburgh. At the time, Hume was already an established philosopher, and I was a young academic who had recently completed my studies at the University of Glasgow and undertaken further education at Balliol College, Oxford.

Our shared interests in philosophy, ethics, and political economy brought us together, and we soon developed a close friendship. We were both members of the Scottish Enlightenment, a period of intellectual and cultural flourishing in 18th-century Scotland. This environment fostered an atmosphere of open discussion and debate, which allowed us to engage in stimulating conversations and exchange ideas.

Our friendship and mutual respect grew over the years, and we continued to influence each other's work. In fact, Hume's writings on political economy, such as his essay "Of the Balance of Trade," likely had an impact on my own thinking as I developed the ideas that would eventually be published in "The Wealth of Nations." Similarly, my work in moral philosophy, as presented in "The Theory of Moral Sentiments," might have informed Hume's own thoughts on ethics and human nature.

Our intellectual partnership and friendship remained strong until Hume's death in 1776, and I have always considered him one of my most significant influences and closest friends.

I say, "Did you and him both work together at the same university ever? I'm afraid I don't actually know a lot about Hume compared to you, as I too like you have been interested in economics that has grown as I've gotten older."

[Adam Smith]: While David Hume and I shared many intellectual interests and enjoyed a close friendship, we never held positions at the same university. Our academic careers took us on separate paths.

As I mentioned earlier, I studied and later held the position of Chair of Moral Philosophy at the University of Glasgow. Hume, on the other hand, pursued a somewhat unconventional academic career. Although he applied for professorships at the University of Edinburgh and the University of Glasgow, he was not successful in securing those positions, partly due to controversies surrounding his religious views and skepticism.

Despite not holding formal academic positions, Hume was a prolific writer and an important figure in the Scottish Enlightenment. His contributions to philosophy, history, and political economy were significant, and he engaged with many scholars and intellectuals of his time, including myself.

Our intellectual exchanges took place outside the confines of a university setting, through correspondence and personal meetings. We shared our thoughts, debated ideas, and learned from each other, all of which contributed to the development of our respective works in philosophy and economics.

I say, "Oh I didn't know that! So how did the two of you mostly interact and exchange ideas if you weren't in the same university? Did you live near one another and meet on occasion or was it primarily some other way you maintained that friendship?"

[Adam Smith]: Our friendship and intellectual exchanges were primarily maintained through correspondence and occasional meetings in person. At the time, letter writing was a common means of communication, especially among scholars and intellectuals. David Hume and I exchanged numerous letters over the years, discussing our ideas, works, and thoughts on various philosophical and economic topics.

In addition to our written correspondence, we also met in person whenever possible. Although we did not live in the same city or work at the same university, our paths crossed at various points throughout our lives. For instance, when I was in Edinburgh, either during my early years as a student or later when I returned to Scotland after my European travels, we would meet and engage in conversations about our intellectual pursuits.

Our friendship was not just limited to intellectual exchanges; we also shared a genuine affection and camaraderie. Our meetings provided opportunities for lively debates, discussions, and the sharing of our latest thoughts and ideas, all of which contributed to the growth and development of our respective works.

Me, "He sounds like he's been a strong partner in your own development. I'm curious, though, how have you noticed your interests evolving in the earlier part of your until the publication of your book? I know you had for instance written another important book on moral sentiments. Have you noticed any significant turning points in your own intellectual viewpoint over time?"

[Adam Smith]: My intellectual interests and viewpoints have indeed evolved over time, as I delved deeper into various subjects and engaged in discussions with other scholars and thinkers.

Early in my career, my focus was primarily on moral philosophy, as evidenced by my work in "The Theory of Moral Sentiments," published in 1759. In this book, I examined the nature of human morality, the role of sympathy in moral judgments, and the foundation of ethical behavior. The ideas presented in this work reflect my belief that humans have an inherent capacity for empathy and that our moral judgments are influenced by our ability to understand and share the feelings of others.

As my interests expanded, I became increasingly drawn to the study of political economy. This shift in focus was influenced, in part, by my observations of the economic changes taking place in Britain and Europe during the 18th century, as well as my interactions with other scholars, such as David Hume. My growing interest in political economy led me to explore the factors that contribute to the wealth and prosperity of nations, which ultimately culminated in the publication of "An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations" in 1776.

Throughout my intellectual journey, there have been significant turning points and moments of growth. For example, my time at the University of Glasgow under the tutelage of Francis Hutcheson greatly shaped my understanding of moral philosophy. Similarly, my European travels and interactions with prominent thinkers, such as Voltaire and François Quesnay, further expanded my intellectual horizons and exposed me to new ideas and perspectives.

In summary, my intellectual development has been a continuous process of exploration, learning, and refinement, influenced by various experiences, interactions, and personal interests over the years.

I say, "One of the things I have noticed about you, that really distinguishes you from other classical economists is just how deeply well read you are in history. Is that accurate you think? You seem to be well read across so many disciplines -- economics, philosophy, history. I'm curious, is that true and what can you tell me about how you manage to bring so many different viewpoints together in your latest book on the Wealth of Nations?"

[Adam Smith]: Thank you for your kind observation. It is true that I have always been an avid reader and have a deep interest in various disciplines, including history, philosophy, and economics. I believe that a broad understanding of different subjects allows one to develop a more comprehensive perspective on the complexities of human society.

In writing "An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations," I sought to incorporate insights from these various disciplines to better understand the factors that contribute to the prosperity of nations. By examining historical examples, philosophical principles, and economic theories, I aimed to create a more holistic and nuanced understanding of the subject matter.

This interdisciplinary approach has helped me to develop my ideas on topics such as the division of labor, the role of self-interest in economic transactions, and the importance of free markets in promoting economic growth and well-being. By drawing on insights from multiple fields, I have been able to explore the intricate connections between human behavior, social institutions, and economic outcomes.

I believe that the integration of different disciplines is crucial for developing a well-rounded understanding of the world and its complexities. It allows one to see the broader picture and to appreciate the interrelatedness of various factors that shape human society and its development.

I say, "This is good segue to move into economics itself. I'm curious how that started. For instance, I could have easily seen you specialize exclusively in philosophy or maybe at least just more focused on it like your friend, David Hume, is known for. What drew you to economics as a field, and how did your interest in moral philosophy influence your perspective?"

[Adam Smith]: My interest in economics emerged gradually as I explored the broader fields of moral philosophy and social sciences. I was fascinated by the interactions between human behavior, social institutions, and the allocation of resources. As I delved deeper into these subjects, I recognized the importance of understanding the economic aspects of human society and how they contribute to the overall well-being of individuals and nations.

My work in moral philosophy laid the foundation for my exploration of economics. The study of human behavior, ethics, and social order provided me with insights into the motivations and principles that underlie economic transactions and the functioning of markets. In "The Theory of Moral Sentiments," I discussed the role of sympathy and the capacity for humans to share the feelings of others. This understanding of human nature helped me recognize that self-interest, when appropriately channeled, can lead to mutually beneficial outcomes in economic exchanges.

As I began to study the principles of political economy, I was drawn to the idea that a nation's wealth and prosperity could be significantly influenced by the economic policies and social institutions in place. By examining historical examples and engaging in discussions with other thinkers, such as David Hume, I was able to develop my own ideas on the subject. This ultimately led to the publication of "The Wealth of Nations," which sought to provide a comprehensive understanding of the factors that contribute to the wealth and success of nations.

In essence, my background in moral philosophy provided me with a unique perspective on economics. This allowed me to explore the connections between human behavior, social institutions, and economic outcomes, and to develop a more holistic understanding of the factors that shape the prosperity of nations.

I say, "That's really interesting. I have a couple follow-up questions I want to ask you about that. It's interesting you say that humans have the ability to share people's feelings. Can you elaborate on that? What does it mean to "share" in this context a person's feelings? Why would we possess those traits also?"

[Adam Smith]: In "The Theory of Moral Sentiments," I introduced the concept of sympathy, which refers to the ability of humans to understand and share the feelings of others. When I say "share," I mean the capacity to mentally place ourselves in another person's situation and to experience, to some extent, the emotions they are feeling. This empathic understanding allows us to respond to others in a compassionate and supportive manner.

I believe that the ability to share and understand the feelings of others is a fundamental aspect of human nature. It is an innate trait that has evolved over time, as it plays a crucial role in maintaining social harmony and fostering cooperation among individuals. Our capacity for sympathy allows us to form bonds with others, navigate complex social situations, and develop a sense of morality that guides our behavior.

Sympathy, in my view, is the foundation upon which our moral judgments and ethical principles are built. When we evaluate the actions of others or consider the consequences of our own behavior, we draw upon our ability to share and understand the feelings of those who are affected by these actions. By placing ourselves in their situation and experiencing their emotions, we can better appreciate the moral implications of our decisions and strive to act in a way that promotes the well-being of others.

In essence, our capacity for sympathy and empathy is an essential part of human nature that enables us to form social bonds, maintain harmony within our communities, and develop a moral compass that guides our behavior in a complex world.

I say, "It seems like one interesting connection between what you're saying and economic exchange is that I see markets and exchange as based not just on moral sentiments but selfish gain. I don't mean that in a judgmental sense. I just mean that economic exchange often is a mechanism by which each person can under some conditions improve their lot. Money exchanges don't require we love each other, for instance. And I think you say something about that in fact. In your recent book you write, "It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own self-interest. We address ourselves not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities, but of their advantages". So I'm curious, is there some tension between your book a few decades earlier on moral sentiments and markets which maybe don't really depend on it?"

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Scott's Mixtape Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.