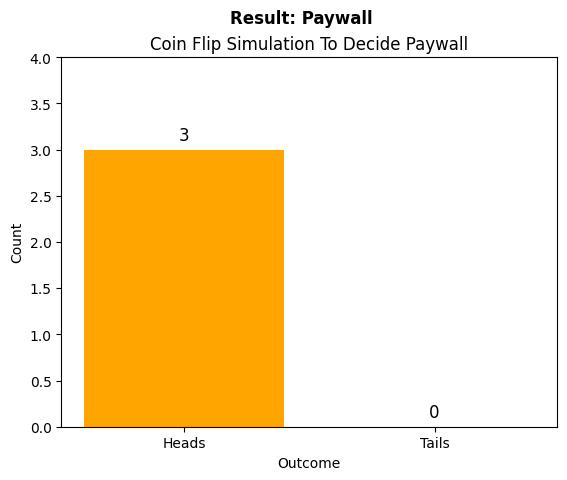

Today’s post is paywalled because I flipped three coins using python and it came up heads every time. Please consider becoming a subscribing member of the substack where you can expect more overwritten articles about AI, pop culture, love, Claude Code and diff-in-diff, as well as pictures of me and my kids!

Obligatory introduction

I regularly think about the purpose of pre-trends in diff-in-diff. And it’s probably because the new estimators allow one, via different syntax choices in econometricians’ own papers and authored R and Stata code, to pick different ways to calculate the pre-trends. So I thought I’d just post a short substack today, not so much arguing there is a right or wrong way to do these pre-trends (though I have a strong opinion), but to offer up my own beliefs about why we do pre-trend tests in the first place.

Falsifiable Hypotheses

I think, personally, that the reason we put up pre-trend tests in diff-in-diff is the same reason we look at things like covariate balance and re-estimating our models on the pre-treatment period (even outside of a diff-in-diff). And that is because we are trying to provide evidence for the identifying assumptions. I’m putting this under a heading of falsifiability because I want to link the somewhat a-theoretical approach to causal inference in the Rubin potential outcomes tradition with something more akin to falsifiability in the Popper-Friedman tradition of scientific theories.

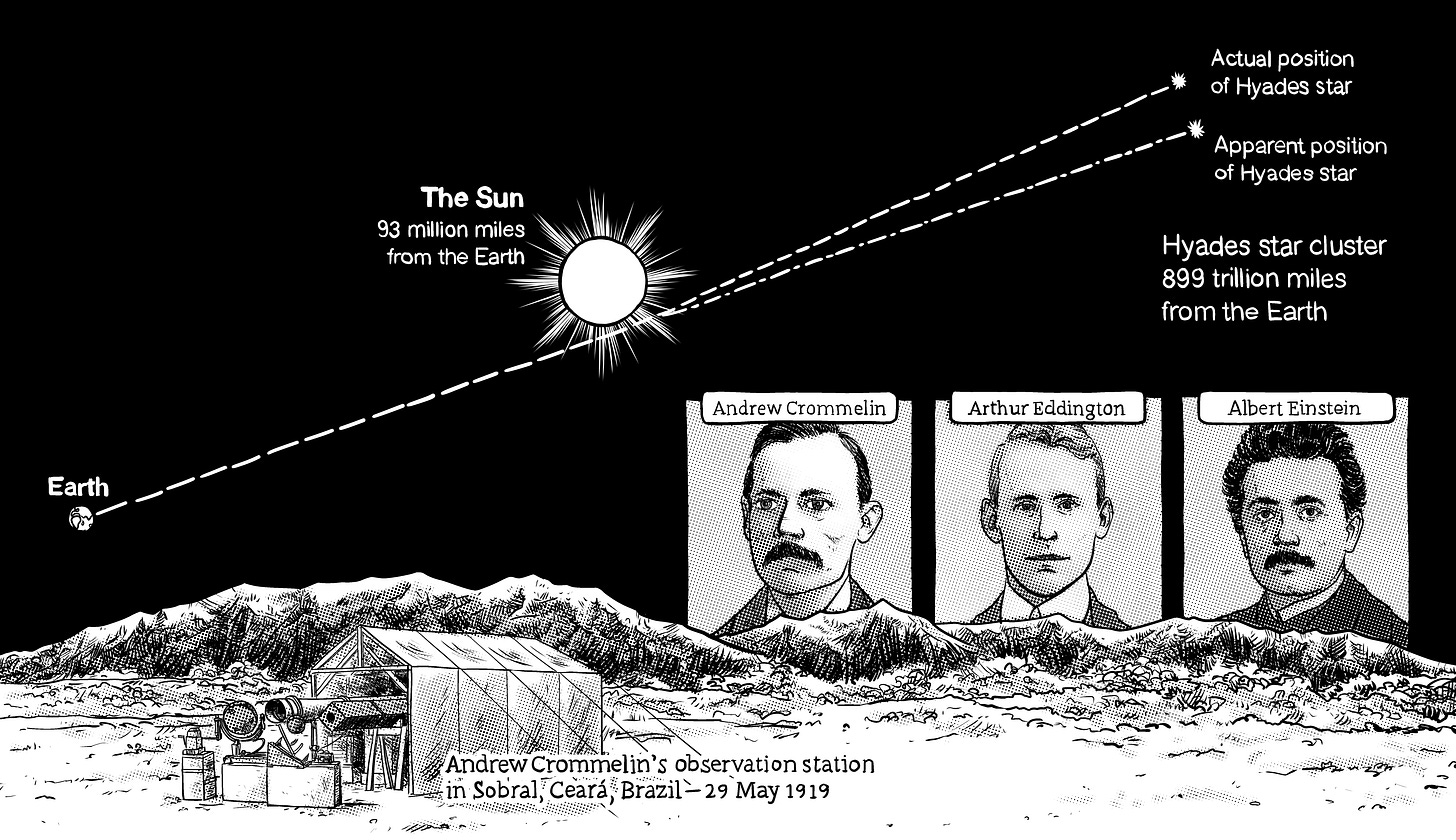

Under the Popper-Friedman tradition of falsifiability being a key part of any scientific theory, what you are typically doing is looking “out of sample” at the logical consequences of the model, but empirically — not theoretically. So if the comparative statics of the model does something like “and not only should you see effects here, they should be precisely something else over here”. You can see that in Einstein’s theory of relativity even — his “model of reality” made an extremely precise prediction about the bending of light around large objects. And astronomers and physicists only managed to work this out several years after its publication with an ingenious natural experiment approach using an eclipse. I wrote about this in the first edition of the Mixtape (in the triple diff subsection where I discuss the third chapter of my dissertation — the most illogical place to put this admittedly). Check out this cool picture my friend Seth Hahne drew for me in the book too.