My guest this week on the podcast is Phillip Levine, the Katharine Coman and A. Barton Hepburn Professor of Economics at Wellesley College in Massachusetts. I’ve only personally met Phil once — at a conference on the family many years ago and just briefly. But I have been a huge admirer of him for many reasons for a long time, ever since graduate school, and I wanted to interview him for a lot of reasons. First, he attended Princeton in the 1980s at that heady time when Orley, Card, Krueger, Angrist and so many others were there. The birth place of the credibility revolution is arguably the Princeton’s Industrial Relations Section where a shift in empirical labor took place that eventually ran through the entire profession and placed it on a new equilibrium. Phil was there, colleagues and students with those people, and himself part of that “first generation” of labor economists who thought that way and did work that way and I wanted to hear about his life and how it passed through, like a river bending and turning, the Firestone library and beyond.

But I also have a special interest in Phil. I actually first learned difference-in-differences from a book that Phil wrote on abortion policy entitled Sex and Consequences (Princeton University Press). I graduated from the University of Georgia in 2007, but the job market had started in 2006, and around the spring when I had accepted my job at Baylor, I was finishing my dissertation. I had one chapter left and it was going to be an extension of Donohue and Levitt’s abortion-crime hypothesis to the study of gonorrhea. My reasoning was that if abortion legalization had so dramatically changed a cohort by selecting on individuals who would have grown up to commit crimes, then it should show up in other areas too. My argument was relatively straightforward and I’ll just quote it here from the article I later published with Chris Cornwell in the 2012 American Law and Economics Review.

“The characteristics of the marginal (unborn) child could explain risky sexual behavior that leads to disease transmission. For example, Gruber et al. (1999) show that the child who would have been born had abortion remained outlawed was 60% more likely to live in a single-parent household. Being raised by a single parent is a strong predictor of earlier sexual activity and unprotected sex, evidenced by the higher rates of teenage pregnancy among the poor.”

It’s funny the order in which things go. I think I somewhat understood what I was doing because I already had planned to do my study before reading Phil’s book. I was going to use the early repeal of abortion in 1969/1970 in five states (California and New York being two of them) followed by the 1973 Roe v. Wade as this staggered natural experiment to see whether abortion legalization led to a drop in gonorrhea a generation later. I had adapted a graph I’d seen by Bill Evans to illustrate how the staggering of the roll out would lead a visual “wave” of declines in gonorrhea in the repeal stages among an emerging cohort that would last briefly until the Roe cohort entered. Visually, I believed you should see a drop in gonorrhea for 15yo starting in 1986 that would get deeper until 1988, flatten, and then disappear completely by 1992.

The design for this idea came from a paper I just linked to above — by Phil Levine. It was entitled “Abortion Legalization and Child Living Circumstances: Who is the “Marginal Child”?” coauthored with Doug Staiger and Jon Gruber, published in the 1999 QJE. It came out two years before Donohue and Levitt’s 2001 QJE on abortion and crime and arguably really set the stage for that paper. The two papers are very different — Phil, Staiger and Gruber are looking at who was aborted using instrumental variables with the five “repeal states” as the instrument. The abstract is worth reading:

“Cohorts born after legalized abortion experienced a significant reduction in a number of adverse outcomes. We find that the marginal child would have been 40–60 percent more likely to live in a single-parent family, to live in poverty, to receive welfare, and to die as an infant.”

They used, in other words, instrumental variables whereas Donohue and Levitt used a lagged abortion ratio measure, if I recall correctly. Phil’s paper really struck me as the more credible design at that time because the staggering of legalization gave such precise predictions — something about the timing, something about the location. It just really haunted me for a long time.

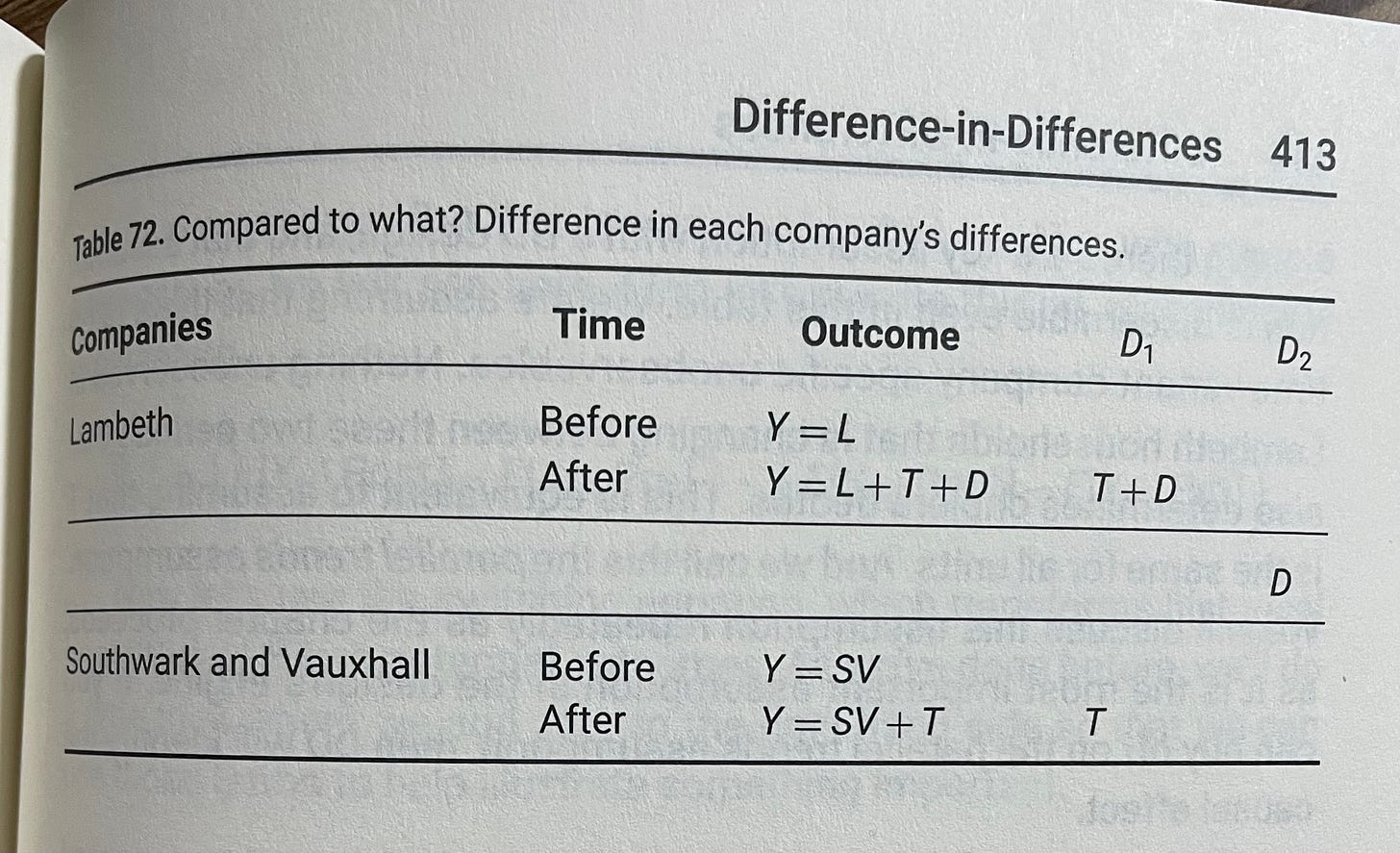

Well, while I was preparing for that project, reading the literature on the economics of abortion, continuing my ongoing interest in the economics of sexual behavior, Phil has a chapter where he sets up for the reader a table explaining something called “difference-in-differences”. While econometrics was my field, I couldn’t recall hearing what that was, because it wasn’t really best I could tell an estimator. Rather it was what we now call a research design. I don’t have the book here at the house, but the table made a huge impression on me because if you just walk through the before and after differencing, even without potential outcomes, you can see with your own eyes exactly why difference-in-differences identifies a causal effect. I have a version of the table in my book, which I’ll produce below.

Once I saw that, it was easy to understand triple differences — a design that many people find very confusing if they only think of it in terms of regression equations. Almost immediately after I understood Phil’s DiD table, I adapted it to my repeal versus Roe context and imagined “Well, what if there were other things happening in these repeal states later? Is there an untreated group I could imagine was affected by those unseen things but which wasn’t treated?” And I thought “Let me use a slightly older group of individuals in the same states as the within-state controls”. That approach — the triple difference — can be seen below in a table I mocked up for a lecture in which I teach triple difference using Guber’s 1994 paper that introduced the design for the first time.

And so I wrote the chapter, and of all my chapters, it was the only one I ever published.

Where am I going with this? I guess what I’m saying is that as luck would have it, I made a monumental jump in my understanding of this “way of thinking” about doing empirical work from a single table in a short little book on abortion policy by Phil Levine. That one table so completely captivated my mind that ever since I have only wanted to learn more about causal inference in fact. As odd as it may sound, something about difference-in-differences really unlocked for me what the whole empirical enterprise was about. As Imbens said, there is something about potential outcomes that just makes crystal clear what we mean by causality, and many of the research designs that have over time been fully mapped onto potential outcomes — difference-in-differences being one — extend that clarity for a lot of us. Phil’s work has consistently been part of the broader education of labor economists about what the Princeton tradition left us — make clear where the variation in the data is coming from, make clear who is and is not functioning as the counterfactual, “clean identification”, carefully collected data, on questions that matter.

Phil has had a very interesting life; I caught only a peek of it from this interview. He opened up and shared about being a young man growing up middle class where family experiences during difficult economic times appeared to cause inside him an interest in labor. He gravitated towards law but a chance research class in college placed him on a new trajectory. His professors encouraged him to go to Princeton because, to put it bluntly, that was in their opinion where the best labor economics was at the moment. So he did. He alluded to graduate school being very hard — something many of us can identify with — but he survived, graduated, and took a job at Wellesley College where he’s been ever since. We discussed his interest in topics in labor economics, his emerging interest in abortion policy, his coauthorships with several people he calls close friends, and his favorite project of all time — a 2019 AEJ: Applied study with Melissa Kearney, a longtime collaborator, on the effect of Sesame Street on educational outcomes, finding strong effects for boys. We also discussed the nonprofit he founded called MyInTuition which is an online calculator that shows the projected cost of college once financial aid is factored in. This topic around the opaque pricing of higher education is something Phil cares deeply about and has a new book on the topic too.

All in all, Phil is an exemplary labor economist and someone I admire greatly. Not just for his careful empirical style and approach, but also because as you can see throughout his life a deep care for people. I have a deep admiration for the labor economists. Most of us are after all workers. We buy the things we need to survive using money we earned from work. Throughout human history, we have lived at the break even condition of survival, many of us not having enough calories to even make it through the day. The researchers who study work, be it economists or not, are studying poverty, one of the most dangerous plagues that has ever been around, far more dangerous than Covid or the plague. In Phil I see someone whose entire life has been about trying to better understand the causes of the wealth of nations, to quote Adam Smith, be it his early work on unemployment insurance, or his later work on children’s television shows. It was a pleasure to talk to him and I hope you enjoy this interview as much as me. Forgive me for this rambling essay.

If you enjoy the podcasts and the substack more generally, please consider supporting it by becoming a subscriber!