Claude Code 18: When the Reclassification Is Massive But the Trends Don’t Change, Something Interesting Is Happening

Digging into why a $11 LLM replication of a PNAS paper works at all

This is Part 18 of an ongoing series on using Claude Code for research. But it’s also my third post on using Claude Code to replicate a paper that used natural language processing methods (specifically, a Roberta model with human annotators). The first part (below) set it up and included a video recording of it.

Claude Code Part 14: I Asked Claude to Replicate a PNAS Paper Using OpenAI's Batch API. Here's What Happened (Part 1)

I’ve been experimenting with Claude Code for months now, using it for everything from writing lecture slides to debugging R scripts to managing my chaotic academic life. But most of those tasks, if I’m being honest, are things I could do myself. They’re just faster with Claude.

Claude Code 15: The Results Are In: Can LLMs Replicate a PNAS Paper? (Part 2)

TL;DR I used gpt-4o-mini to replicate the text classification from Card et al.’s PNAS paper on 140 years of immigration rhetoric. Here’s what happened:

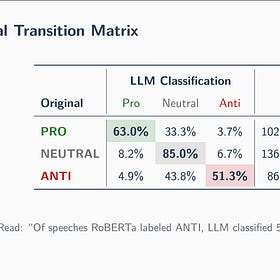

In Part 2 (linked above), I showed you the punchline: gpt-4o-mini agreed with the original RoBERTa classifier on only 69% of individual speeches — but the aggregate trends were virtually identical. Partisan polarization, the country-of-origin patterns, the historical arc — all of it survived.

That result bothered me. Not because it was wrong, but because I didn’t understand why it worked. A third of the labels changed. That’s over 100,000 speeches reclassified. How do you reshuffle 100,000 labels and get the same answer?

Today’s part covers the puzzle of why those results work at all — and where we’re going next. Today I spent an hour with Claude Code trying to figure that out. Below is what happened and is described in another video. I don’t complete the progress, but you can see again me thinking out loud and working through the questions that remained.

Thanks for following along with this series. It’s a labor of love. All Claude Code posts are free when they first go out, though everything goes behind the paywall eventually. Normally I flip a coin on what gets paywalled, but for Claude Code, every new post starts free. If you like this series, I hope you’ll consider becoming a paying subscriber — it’s only $5/month or $50/year, the minimum Substack allows.

The Conjecture: Symmetric Noise

The other day, I reclassified a large corpus of congressional speeches and presidential communications into three categories: anti-immigration, pro-immigration and neutral. It wasn’t exactly a replication of this paper from PNAS, but more like an extension, as their original paper used a Roberta model with 7500 annotated speeches from around 7 or so students who read and classified the speeches, thus training the model on them, and then predicted the other 195,000 off it. I extended it using gpt-4o-mini, without any human classification, to see to what degree it agreed with the original and whether that disagreement mattered. And I found significant reclassification and yet the reclassification had no effect on aggregate trends as well as various ordering within subgroups.

I have found this puzzling but had a conjecture which was that the gpt-4o-mini reclassification was coming from the “marginal” or “edge speeches”, and since the aggregate measure was a net immigration measure of anti minus pro, maybe it was just averaging out noise leaving the underlying trends the same.

I kept thinking about this in terms of a simple analogy. Imagine two graders scoring essays as A, B, or C. They disagree on a third of the essays — but they report the same class average every semester.

That only works if the disagreements cancel. If the strict grader downgrades borderline A’s to B’s and also downgrades borderline C’s to B’s at roughly the same rate, the B pile grows but the average doesn’t move. The signal is the gap between A and C. The noise is the stuff in the middle.

That’s what I suspected was happening here. The key measure in Card et al. is net tone — the percentage of pro-immigration speeches minus the percentage of anti-immigration speeches. If gpt-4o-mini reclassifies marginal Pro speeches as Neutral and marginal Anti speeches as Neutral at similar rates, the difference is preserved. The noise cancels in the subtraction.

But I wanted to test this formally, and I wanted to do it using Claude Code so that I could continue to illustrate to people using Claude Code in the context of actual research which is a mixture of data collection, conjecture, testing hypotheses empirically, creating a pipeline of replicable code, and summarizing results in “beautiful decks” so that I could reflect on them later.

Two Tests for Symmetry

First, on the video you will see that I had Claude Code devise and then build two empirical tests.

Test 1 computed the net reclassification impact: for each decade, what’s the difference in net tone between the original labels and the LLM labels? If the reclassification is symmetric, that difference should hover around zero.

Test 2 decomposed the flows. Instead of looking at the net effect, we tracked the two streams separately: the Pro→Neutral reclassification rate and the Anti→Neutral reclassification rate over time. If they track each other, the cancellation has a structural explanation.

The results were honest. The symmetry which I had hypothesized isn’t perfect — the t-test rejects exact symmetry (p < 0.001) which was a test I did not explicitly request, but which Claude Code pursued given my general request for a statistical test. Anti→Neutral flow is consistently larger than Pro→Neutral, with a symmetry ratio of about 0.82. The LLM is a bit more skeptical of anti-immigration classifications than pro-immigration ones. And you saw that actually in the original transition matrix because there was more reclassification going from Pro→Neutral just looking at the aggregate data. Plus the sample sizes were different (larger for the original Pro than the original Anti categories) and very large. So all this really did was confirm what was always there in front of my eyes.

But the residual is small. Mean delta net tone is about 5 percentage points — modest relative to the 40-60 point partisan swings that define the story. The mechanism is asymmetric but correlated, and averaging over large samples absorbs what’s left.

Jason Fletcher’s Question

My friend Jason Fletcher asked a good question: does the agreement break down for older speeches? Congressional language in the 1880s is nothing like the 2010s. They wrote in a different style, and who knows how contemporary LLMs handle old versus new speeches. If gpt-4o-mini is a creature of modern text, we’d expect it to struggle with 19th-century rhetoric. But since there are a lot of texts in the training data, maybe they handle it the same. Maybe young students at Princeton will struggle moreso than LLMs with older text. It’s more an empirical conjecture than anything else.

So Claude Code built two more tests: agreement rates by decade and era-specific transition matrices. I will dive into the actual results tomorrow all at once, but the punching for today was not really a total surprise to me. The overall agreement barely moves. It’s 70% in the 1880s and 69% in the modern era. The LLM handles 19th-century speech about as well as 21st-century speech. Which fit my priors on LLM strengths.

But beneath that stable surface, the composition rotates dramatically. Pro agreement rises from 44% to 68%. Neutral falls from 91% to 80%. So even though they cancel out in aggregate, there are some unique patterns. It is a different kind of balancing act. This seemed more consistent with some off my priors about the biases of the human annotators that created the original labels. Perhaps humans are just better at labeling the present (i.e., 68% agree on pro speeches) than the past (i.e., 44%). Which is an interesting finding probably worth thinking about.

Two More Things Running Overnight

But then once we had the symmetry story, I wanted to push further. And here was the idea I went with on the video recording. Both of which required collecting more data, and that gave me a chance to both showcase some old tricks (i.e., using gpt-4o-mini for inexpensive batch requests, but doing it using Claude Code to create the scripts so that he viewer/reader could see it themselves how straightforward it was), and some new ones as well. Specifically —

Classifying a thermometer. Instead of classifying speeches into three bins, I sent all 305,000 speeches back to OpenAI scored on a more continuous scale from -100 (anti-immigration) to +100 (pro-immigration). It was technically still multi-valued, but ranging from -100 to +100, we will at least get a nice picture to see what this distribution of speeches looks like according to gpt-4o-mini. But the idea was borne out of my hypothesis about the reclassification happening for the marginal speeches. Specifically, if the reclassified speeches cluster somewhat symmetrically around zero on this multi-valued scale ranging from -100 to +100, then that might be evidence that confirms they were always marginal cases sitting on the decision boundary and thus reclassifying was simply on noisy speeches that on average canceled each other out thus leaving the trends largely intact in the extension. Those batches are processing at OpenAI now.

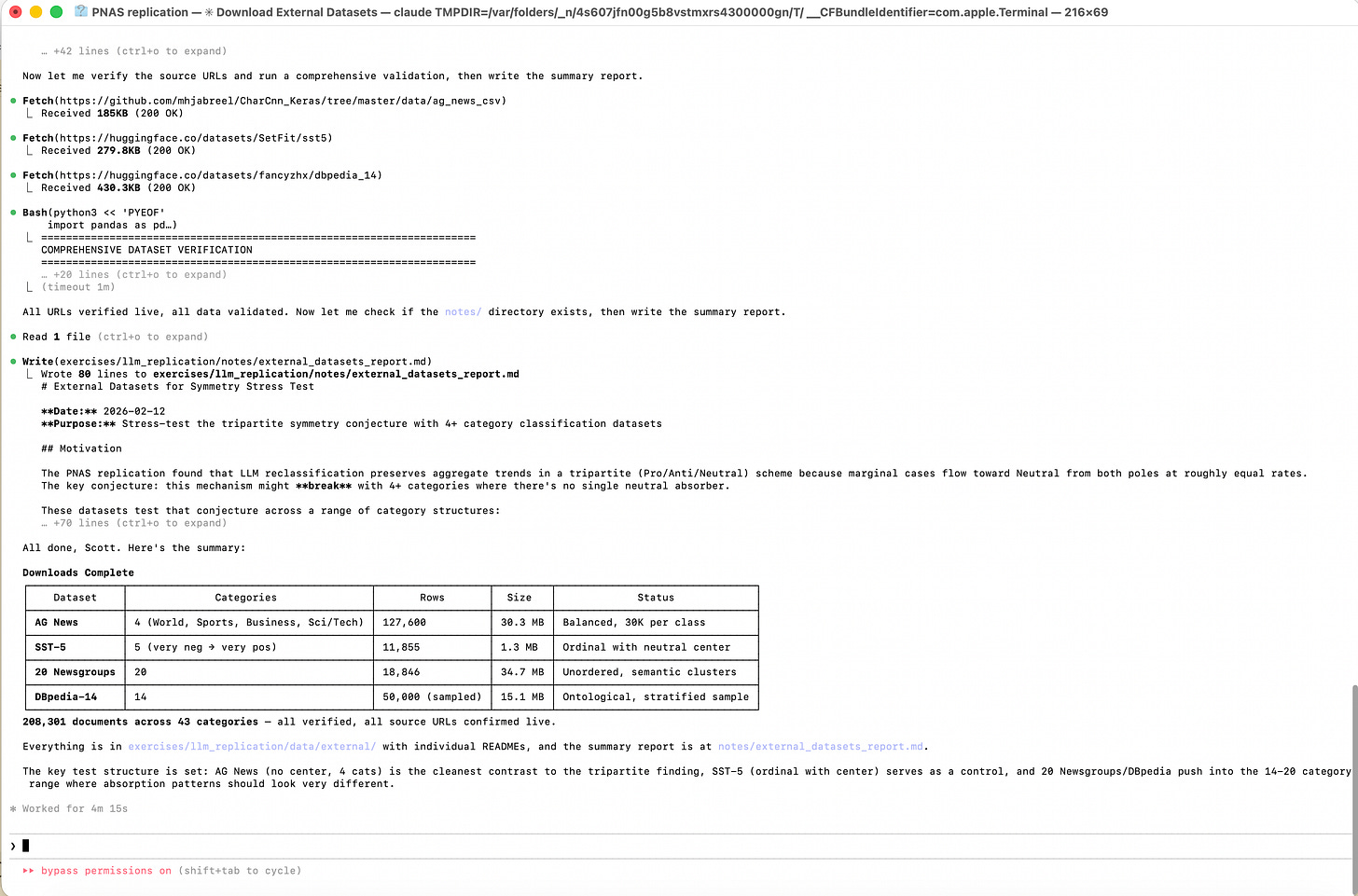

External datasets. The other part of my conjecture, though, had to do with the original classification being anti, neutral and pro-immigration. Was the finding that the LLM reclassification was both substantial and had no effect at all on the original finding simply an artifact of that tripartite classification? Why? Because that original classification has a built-in symmetry mechanism — two poles and a middle — which would have to break with four or more categories. For instance, if the classification was not “ordered” but was more of a distinct categories (e.g., by race), then it’s not clear you should even theoretically get the same result as what we found. So to test this, I spun up a second Claude Code agent using

--dangerously-skip-permissionsin the terminal to search GitHub, Kaggle, and replication packages for datasets with 4+ human-annotated categories. At the time of this writing, that process is done. It only took 4 minutes to web crawl, find those datasets, and store them locally. I will review this tomorrow on a new post.

What’s Next

Tomorrow I’ll have thermometer results. I’ll download them on video, analyze them and report findings in a new deck. I will also do the same in real time with the external datasets. If the thermometer shows reclassified speeches clustering near zero, that’s strong evidence for the marginal-cases story. If the 4+ category datasets show the same pattern, the theory generalizes. If they don’t, tripartite classification is special and that’s interesting too.

This is the part of research I love — when you have a conjecture and the data to test it is literally being collected overnight. But what I love is that that entire part of it was facilitated by Claude Code which is giving me back time to think instead of undertaking the tedious tasks of coding this up.

Thank you again for reading and supporting the substack, which is a labor of love! I hope you find these exercises useful. Please consider becoming a paying subscriber of the substack! At $5/month, it’s quite a deal! Tune in tomorrow to see what I find!

Hi Scott. Super interesting experiment and blog!

I‘m currently engaged in a similar endeavor with forum posts. But I‘m running all the time into token restrictions when trying to use cheaper batch processing, though in Google Cloud. OpenAI is supposedly even more restricted in this regard. To understand your workflow and data - when you say 300k documents - are these chunks of speeches? What is the overall token amount of the speech data?

Thanks - and looking forward to read your continued blog tomorrow.

Thanks for sharing this so publicly, Scott. I'm really enjoying following along and also learning how to use this approach in my own research as well.

What processes are you using for recording the steps that you've taken for quality assurance as a human? As I imagine, that would be really interesting and, in some instances, necessary to report if this was ever to be published as peer-reviewed research.