Embedded in this post is a video interview I did with Dr. Rick Strassman, professor emeritus of psychiatry at University of New Mexico medical school, and pioneer in the scientific study of psychedelics. You can look through his cv here though if you want to get a quick glance of his academic career but I grant most people reading this, given my audience of academics and quantitative social scientists, probably aren’t familiar with him. Let me briefly tell you a little about him.

Who is Rick Strassman?

Rick Strassman is an important character in the modern story of psychedelic therapy because he was the first person in the US to conduct study the effect of any psychedelics on humans following the enactment of the Controlled Substance Act in 1970. Rick chose a relatively obscure (at the time) tryptamine called N,N-Dimethyltryptam, or more popularly “DMT” for that project. DMT is the active compound in a Brazilian ceremonial psychedelic drink called ayahuasca which has been experiencing a surge in popularity over the last few decades (see next image from Google ngram).

The above graph would make it appear that DMT has been around ever since the 1960s, just like many classic psychedelics, and that’s definitely true. But it’s nowhere near as well known as LSD, which is what most people, if they know anything about illicit psychedelic usage associate with that drug.

https://smallpharma.com/insights/brief-history-dmt/

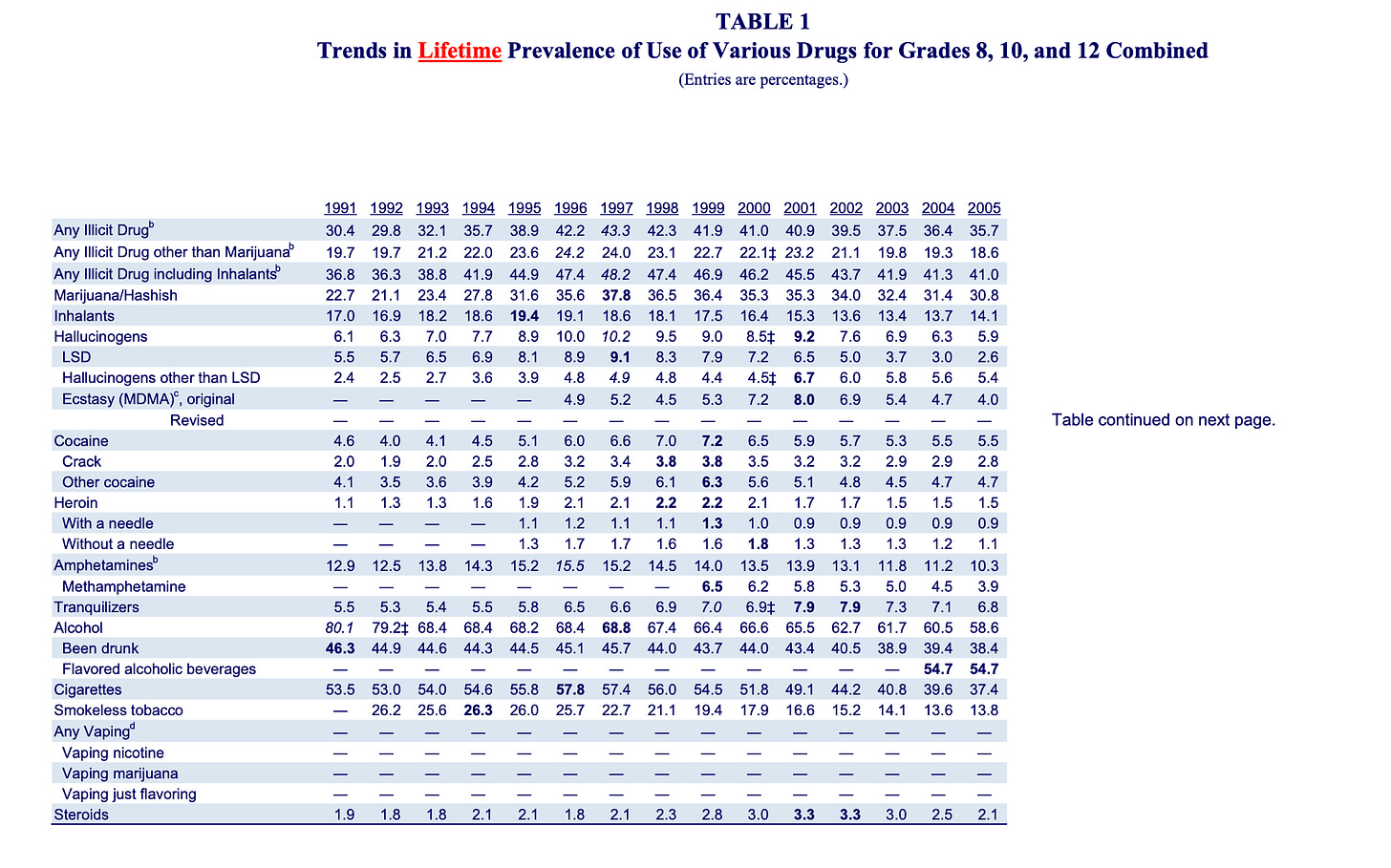

The Monitoring the Future survey is a nationally representative survey of adolescents and high schoolers from which we can learn cross-sectional trends in drug experimentation, among other things. Under the category of “hallucinogen” are three types of drugs: LSD, MDMA and “everything else not LSD”. LSD has historically been since the 1960s the most well known and widely abused psychedelic until around 2001 when factors in the illicit manufacturing of domestic LSD resulted in a national drought of the compound.

But let’s return to Rick Strassman. In the mid to late 1980s, a group of scientists made a bold long term bet that by conducting scientifically valid studies of psychedelics they might be able to persuade the US government that these compounds had medical value and therefore reintroduce it back into the treatment protocols for addiction and mental illness. Rick was one of these people and in the mid 1980s he began to transition away from his research interest in melatonin to studying DMT.

But why study DMT? Why not LSD given it was the more prevalent? Because as he explains in this interview, LSD had tremendous negative cultural baggage. LSD may even have been one of the drugs chiefly responsible for the Controlled Substance Act in the first place as it was so central to the public health problems of recreational drug use in the 1960s. And because Rick was trying to get off the ground federally approved clinical research at a state university medical school on psychedelics, which was going to require navigating two regulatory hurdles — the DEA and the FDA, neither of which anyone had ever successfully done — he chose DMT because it was obscure.

In this interview, part 1 of a 3-part interview series I did, Rick tells his story of how he became interested in psychedelics in the first place, the personal struggles he had as a young man, and the planning it required to successfully complete his DMT trials at the height of the War on Drugs. He candidly shares that the interest was personal. As an undergrad at Stanford University, he developed a somewhat radical theory that the pineal gland was, for lack of a better way to summarize it, somehow connected to human spirituality. And the only way to study the pineal gland was to go to medical school, but fresh off the Controlled Substance Act chilling effect on psychedelic research, Rick learned that telling admissions committees that was an easy way to get a rejection. He soon learned that if he wanted to study psychedelics as a scientist, he would have to keep that piece of information private.

There are many things about this interview that I find interesting, much of what has little to do with psychedelics or the science even itself. I think what I find so interesting about Rick, as well as others involved in this scientific story of psychedelic therapy, is the fortitude it must have required to navigate the Kafka-like labyrinth of the DEA and FDA in the late 1980s. So the fact that Rick not only attempted it, but managed to successfully get funding and approval to do it, resulting in two articles published in psychiatry’s top journal, Archives of General Psychiatry, is a remarkable achievement. It would be like getting two sequential hits in American Economic Review or Science on a topic that no one would touch with a ten foot pole.

Rick’s work ultimately paved the way for most of this new research associated with big names like Roland Griffiths and Rick Doblin. Doblin’s own dissertation for Harvard Kennedy School in 2000 entitled “Regulation of the Medical Use of Psychedelics and Marijuana” describes Rick’s success and incorporates that into Doblin’s own model. But Rick largely quit this research after completing it. You get the sense from his story that this line of research was for him personally and professionally complicated. He published a best selling book, DMT: The Spirit Molecule, in 2000, but left UNM medical school. He is now retired and writes full time.

I think this is an interesting story. He is very candid with who he is, his journey, and we discuss in detail just the ins and outs of getting through the DMT work. I hope you enjoy this first part of a three part interview. Please consider subscribing to support the work and so that can watch the video yourself!

Help Wanted: 100,000 Psychedelic Facilitators

Moving on to other issues now, I’d like to make a comment about the production function of psychedelic therapy. What is the cost minimizing production function for psychedelic therapy that can scale to the level for what is likely coming? Production functions can result in scale depending on the availability of necessary inputs. The ability to scale psychedelic therapies depends on a lot of things, not the least of which is government approval, but that is only the necessary condition. Scale also requires a production function that can scale from the trivially small levels used in experimental trials to a national equilibrium that may in fact be very high. Without a production function that can scale, psychedelic therapy will not be able to maximize the net positive expected value associated with these therapies.

Production functions are economics modeling jargon in which society takes scarce capital and labor inputs and through some recipe combines them to produce something valued at an amount that is greater than the sum of its parts. Along the isoquant of any production function are marginal changes in capital and labor ratios, too, and presumably the production of psychedelic therapy is no different. You take a molecule, like MDMA, and ingest it. You get better, right? No.

Psychedelic therapy involves more than merely ingesting some molecule. It also involves labor inputs — workers who function as part nurse, part psychologist, part life coach, and sometimes, part priest. There are meetings that take place leading up to the “session” in which the person’s mindset is prepared and expectations managed. There’s the experience itself. And then there’s the post-op period in which the patient, well after the psychedelic experience has ceased, works closely with the therapist to do what is sometimes called “integration work”. The worker, in other words, appears to be a crucial part of the efficacy of psychedelic therapy.

Insofar as the production function requires both capital and labor inputs, we need to know what precisely goes into the labor side, because at moment it appears that those workers are scarce to the point of being non-existent. People like Stan Grof, Bill Richards, Walter Pahnke — psychiatrists and researchers, largely connected with Maryland healthcare institutions like Johns Hopkins med school — and others helped develop a therapeutic modality that accommodated what psychedelics did, but when the Controlled Substance Act was passed, that work was sort of overlooked or forgotten about and never got integrated into formal training of licensed therapists in masters or doctoral programs. Training in psychedelic therapy was kept alive informally after the Controlled Substance Act underground, but only regionally, along the West and Pacific Northwest coastal area, and largely outside of academia.

Well, look closely at the work that MAPS therapists are doing by perusing this training manual. Go back and listen to my interview with David Erritzoe. Read the papers. It does seem that the psychedelics are a critical input in the production function of psychedelic therapy benefits, but it’s not clear what the role of the human worker is because to my knowledge there are no studies in which a multi-arm approach was conducted with placebos, therapist only, psychedelics only and the combined. Still, best I can tell, the therapist inputs are crucial.

So, let’s say they are crucial. Doesn’t mean that they must be PhDs in Psychology. Doesn’t mean they must be state licensed LCSWs. For one, psychedelic therapies used don’t even seem to be connected to the formal training you get in masters and doctoral programs at large. Like I said, those therapies went somewhere after the Controlled Substance Act, but wherever they went, it wasn’t into the human capital you get in most recognized PhD and masters programs for psychology or social work. This I think matters because to scale the production of psychedelic therapy, we must hire the same labor inputs used in the trials.

SUTVA Violations and Psychedelic Therapy

One of the lesser known assumptions in causal inference is the Stable Unit Treatment Value Assumption, or SUTVA. There are two broadly conceived ways to violate SUTVA. First, if my potential outcome in either state of the world varies when another person makes a treatment choice, then there is a direct spillover to speak between her treatment and my potential outcome. That means my potential outcome is “unstable”. This is the most popular understanding of SUTVA if there is one and it largely focuses our attention on key design elements like ensuring no contamination of the control group from the treatment group interactions.

But a lesser known violation is the “no hidden variation in treatment” (Imbens and Rubin 2015). For my purposes here, it means in simplest words that all units receive the same homogenous dose. Well, this is really crucial when considering issues of scale and external validity. Put aside that the randomization has been over small often underpowered populations of non-random volunteers with many conditions, like prior psychotic episodes, used to screen out. Those alone make the local average treatment effect parameter a bit challenging to extrapolate. The “no hidden variation in treatment” requirement applies not just to, say, requiring that each patient receive 75mg of MDMA. It requires that the patient receive 75mg of MDMA and integration and preparation work with the therapist.

One of the ways that external validity can fail, in other words, is with SUTVA violations. Everything we know from the lab can be true and yet if we scale psychedelic therapies by hiring therapists who are not like those used in the experiments, then it is literally introducing hidden variation in treatment. And this I think is not something I heard talked bout, and yet this is very clearly something that is emerging because to end with where I started, “Need for 100,000 Psychedelic Facilitators is Real”.

When is psychedelic reforms bipartisan?

When you look closely at the reforms underway, there’s two patterns worth noting when trying to parse what gets bipartisan support. This really only seems to apply to the medical models; I don’t get a sense of what is predicting the decriminalization at the municipality level that Decriminalize Nature is driving. Bipartisan support appears to come from universal concern for end-of-life suffering and universal concern for our veterans. Consider two pieces of evidence.

Booker (D-NJ) and Paul (R-KY) introduced the Right to Try bill. It gives people with terminal illnesses the right to try a medication that has passed Phase 1 trials.

Rick Perry, former governor of Texas, in full support of MDMA therapy for veterans.

The city level decriminalizations have been far more focused on human rights, freedom of religion, environmental styled reasoning though. Also those places that undertook reforms most likely had large-enough populations of consumers. Would love to see analysis of what characteristics are predicting those cities to flip.

Video Transcript

Scott Cunningham:

I'm starting a new series on the oral history of psychedelic medication and legal reform after the Controlled Substance Act of the early to mid-1970s. Some of you may know this, some of you may not, but psychedelic medication, psychedelic being psilocybin or magic mushrooms, ayahuasca or active compound DMT, or a non-psychedelic, but often associated with it, MDMA, they've all been carefully studied over the last 25 years after the Controlled Substance Act in experiments on humans. And they have been quietly pushed forward by some scientists who managed to navigate a labyrinth of regulations to get these experiments done in oftentimes academic settings. And as a result of it, there has been medical breakthroughs discovered in the use of therapist-assisted psychedelics for treating depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. And at the moment, we are probably... There has been three phases of randomized control trials for psilocybin at the FDA, as well as MDMA. And they have both been granted medical breakthrough status for treating depression and PTSD, respectively.

The story of how we got from the Controlled Substance Act of the early seventies to a period right now where not only is there experimentation on humans, but that there has already been over two dozen cities that have decriminalized psychedelics, as well as the state of Oregon. And there appears to be we're on the cusp of a medical model where you will be able to get treatment for depression and PTSD using therapist-assisted MDM and psilocybin. The story of how we got there is the story of specific scientists. And what I'm doing is an oral history with as many people as I can, to learn more about these scientists and these legal reformers, to hear their stories about how they managed to get this work done.

The first person that I'm interviewing is Rick Strassman, a psychiatrist. He's now emeritus, I think at the University of New Mexico Medical School. He was the first scientist or the first person at all in the post-ban era during the Controlled Substance Act or early 1970s, he was the first scientist to get approval for studying psychedelics on humans. It was a study done in 1990. The results of it were published in the top psychiatry journal in 1995. And it was about 60 subjects that were given intravenous dosages of a compound called DMT, which is a lesser-known classic psychedelic. Probably if you were a kid, you never heard of it unless you were paying close attention to certain kinds of writings. But it's the active compound in the Brazilian religious ceremony ayahuasca. Rick managed to get this work done. He required a tremendous amount of fortitude. His story is very interesting. So he agreed to sit down with me for three interviews.

This is going to be different than the other interviews that I've been doing primarily with economists because this is something that I'm wanting to bring to the attention of more social scientists, but do it in the same way that I do it with the other research, which is to just simply allow people to tell their stories and to be with them as they tell those stories and to learn more about them. The story of just getting research done on something as stigmatizing as psychedelics in a university setting, having to navigate the regulations of the Drug Enforcement Agency, as well as the FDA, it's just a story that's very inspiring, regardless of whether you're interested in the subject matter, all of the rejections and just the grit that he showed. It also, I think, tells us a little bit about the characters that are involved in this reform that's happened and the scientific work that's happened. I hope that you appreciate it, or I hope that you get a lot out of it.

Scott Cunningham:

Okay. It is my pleasure to sit down with Rick Strassman. Rick, thank you so much for being on the podcast.

Rick Strassman:

Thanks, Scott.

Scott Cunningham:

Rick, before we get started talking about substantive things in your career, I was wondering if you could just tell the listener a little bit about your background. Where did you grow up, and what is your training? And just a little bit about how you got to where you are.

Rick Strassman:

Well, I was born and raised in Southern California, a conservative Jewish household. Got Bar Mitzvah-ed, then drifted off to psychedelics and Zen Buddhism for the next 30 years or so. Let's see. Well, I started off with this particular line of inquiry like research is me search. The very first time I smoked marijuana, I had a fully psychedelic experience. There were purple clouds coming out of my speakers. I was out of body traveling over Claremont, California with my friend who was sitting on the floor next to me. And as a kid, I was always interested in chemistry. I had a chemistry set. I worked in my garage for hours and hours, and I made fireworks and bombs as well. I was interested in excitement and colors and smoke and sound and edgy stuff just at the point of being dangerous. When I had my first experience like that, I was just amazed that within a period of 10 minutes after smoking this thing, I was in a completely different space and I thought, "Chemistry. It's chemistry."