Claude Code 22: Final Entry Into Classification of Speeches with Claude Code and OpenAI gpt-4o-mini (Part 5)

Today is the fifth and last entry into my replication of the Card, et al. PNAS paper. You can find the others here in order from 1 to 4:

In today’s post, I conclude with analysis of the latest batch to openAI where I sought a continuous rescoring of the original speeches on what’s called a “thermometer”. The values ranged from -100 (anti-immigration) to +100 (pro-immigration). I also had Claude Code find four more datasets that were not using simple “-1, 0, +1” classifications like the original Card, et al. paper had to see if the resins why gpt-4o-mini reclassified 100,000 speeches but did not have any effect whatsoever on the trends was because of the three-partite classification or if it was something else.

In the process of doing this, though, I noticed something strange and unexpected. I noticed that the gpt-4o-mini reclassification showed heaping at non-random intervals. That is a common feature ironically of how humans respond to thermometers in surveys, but it was not something I had explicitly told gpt-4o-mini to do when scoring these speeches. I discuss that below. And you can watch all of this by viewing the video of the use of Claude Code to do all this here.

Thanks again everyone for your support of the substack! This series on Claude Code, and the substack more generally, is a labor of love. I am glad that some of this has been useful. Please consider supporting the substack at only $5/month!

The LLM Heaped Like a Human and Nobody Told It To

Jerry Seinfeld’s wife once said that if she wants her kids to eat vegetables, she hides them on a pizza. That’s been the operating principle of this entire series. I’ve been replicating a PNAS paper — Card, et al on 140 years of congressional speeches and presidential communications about immigration — not because the replication is the point, but because the replication is the pizza. The vegetables are Claude Code and what it can do when you point it at a real research question.

My contention has been simple: you cannot learn Claude Code through Claude Code alone. You need to see it assisting in the pursuit of something you already wanted to do. Which is why this has been two things at once from the start. First, a demonstration of what’s possible when an AI coding agent builds and runs your pipeline. Second, an actual research project — one where the LLM reclassification of 285,000 speeches turned up things I didn’t expect to find.

And this series is about that. I use Claude Code at the service of research tasks so that you can see it being done by first following a research project. This is how I’m “sneaking veggies onto the pizza” so to speak — by making this series about the research use cases, not Claude Code itself, my hope is that you see how you can use Claude Code for research too.

Where we left off

In the first two parts of this series, we built a pipeline using Claude Code and OpenAI’s Batch API to reclassify every speech in the Card et al. dataset. The original paper used a fine-tuned RoBERTa model. Around 7 students at Princeton rated 7500 speeches which were then used with RoBERTa to predict a couple hundred thousand more.

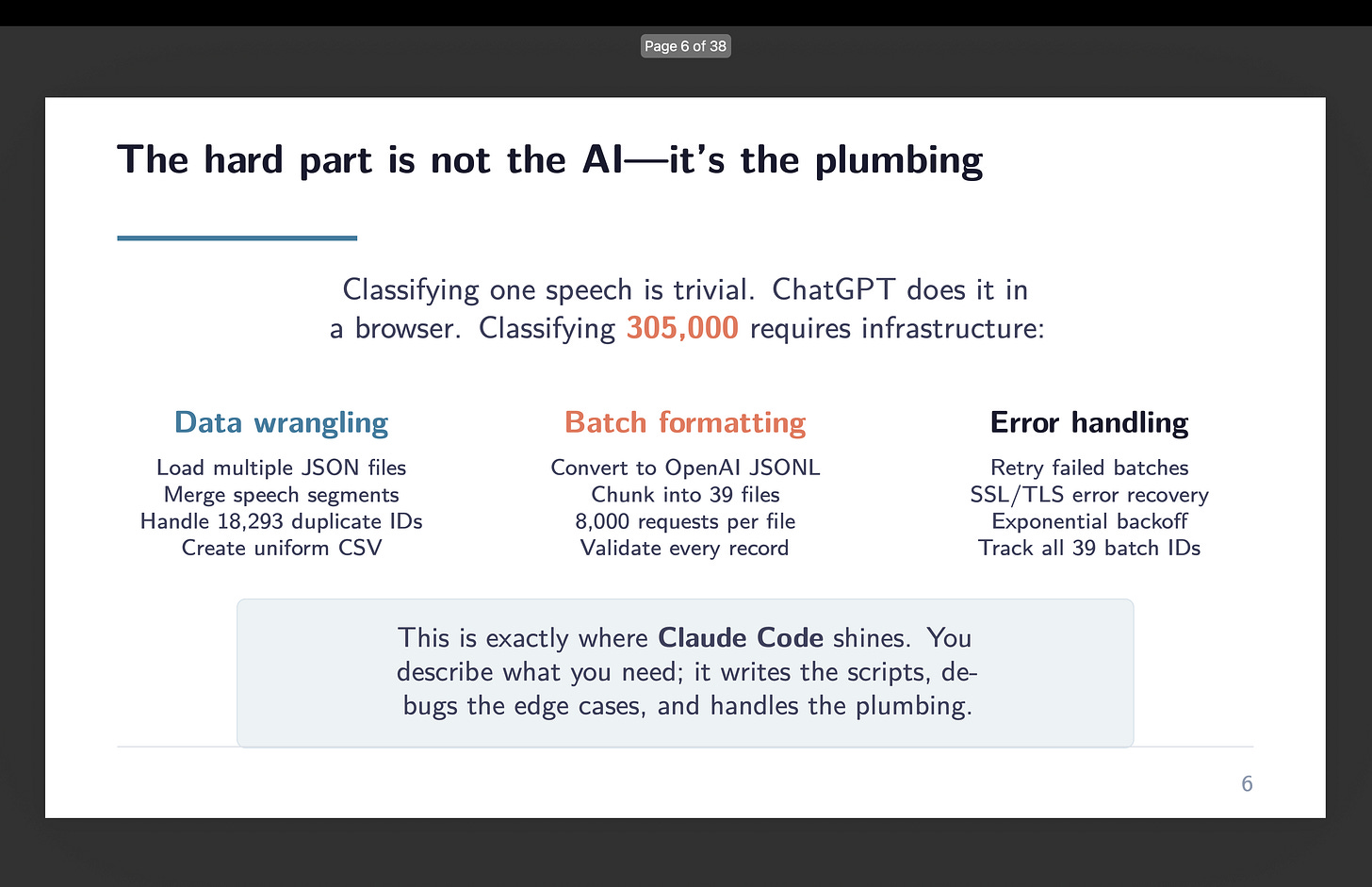

But we used gpt-4o-mini at zero temperature, zero-shot, no training data. The total cost for the original submission was eleven dollars. The total time was about two and a half hours of computation, most of it waiting on the Batch API. And when I redid it a second time, it was just another $11 and another couple hours. Making the total cost of all this around $22 and more or less an afternoon’s amount of work.

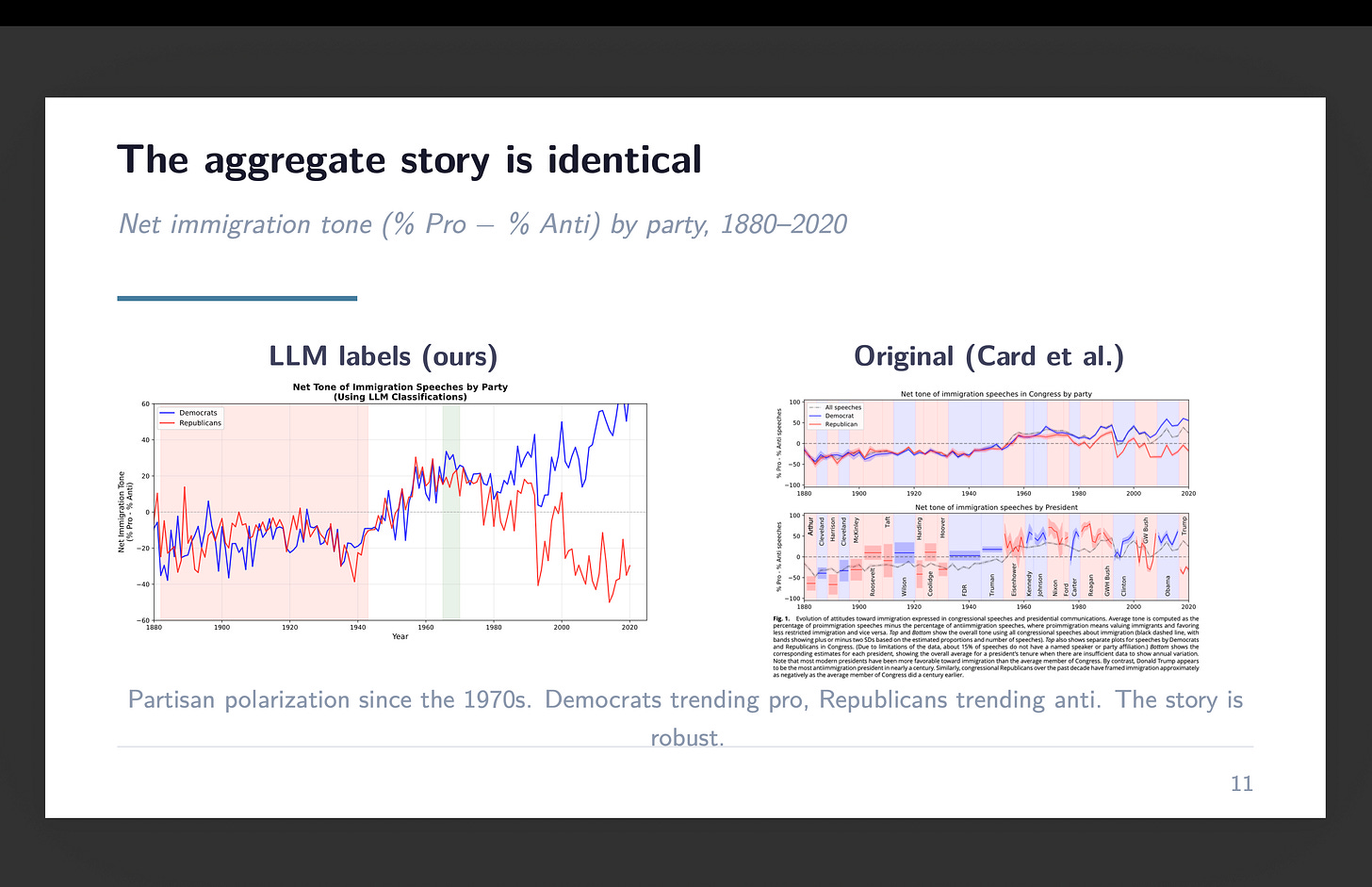

The headline result was 69% agreement with the original classifications. Where the two models disagreed, the LLM overwhelmingly pulled toward neutral — as if it had a higher threshold for calling something definitively pro- or anti-immigration. But here’s the thing that made it publishable rather than just interesting: the aggregate time series was virtually identical. Decade by decade, the net tone of congressional immigration speeches tracked the same trajectory regardless of which model did the classifying. The disagreements cancelled out because they were approximately symmetric.

The thermometer

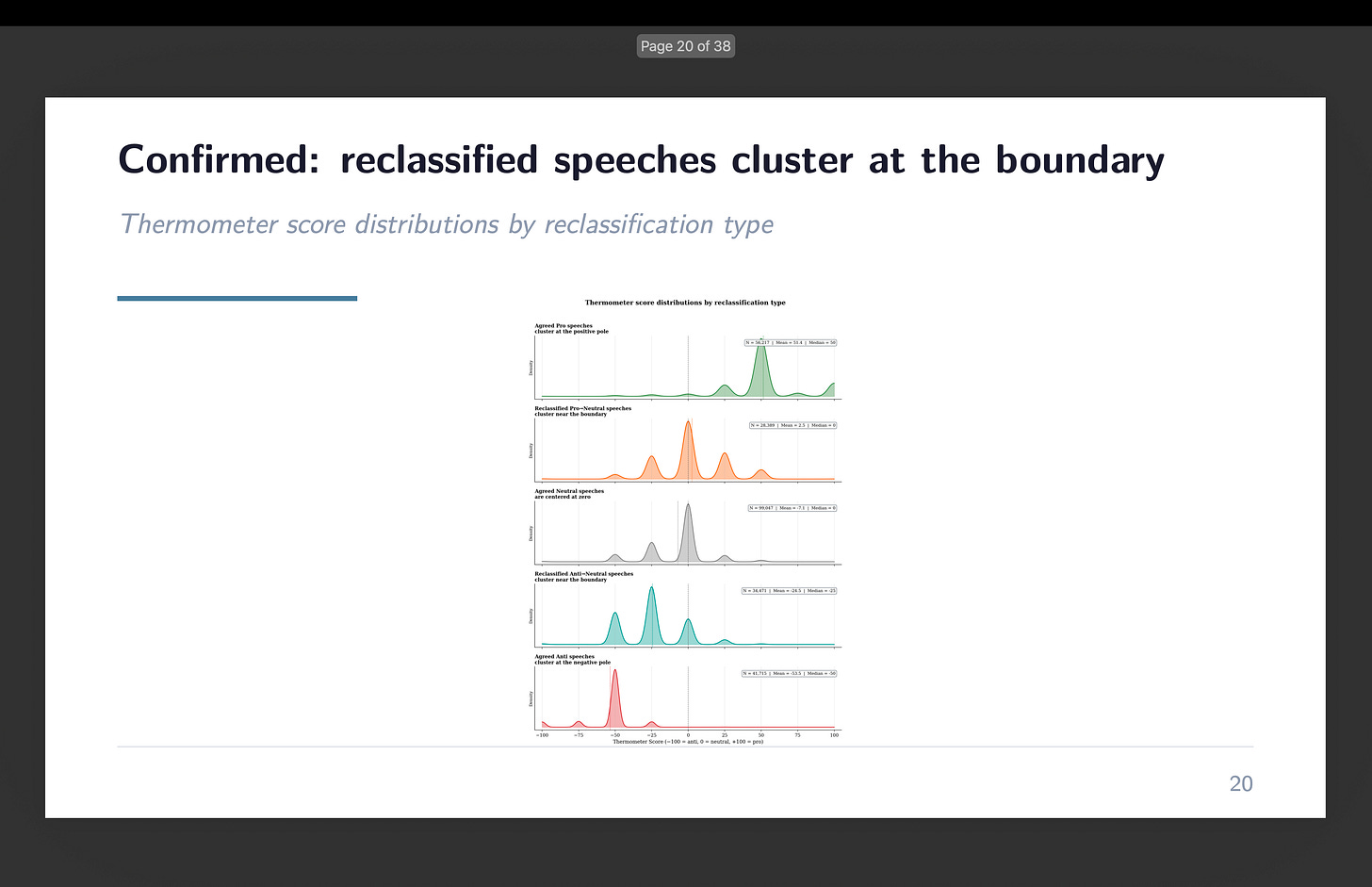

For the second submission, we wanted to go deeper. Instead of just asking the LLM for a label — pro, anti, or neutral — we asked it for a continuous score. A thermometer. Rate each speech from -100 (strongly anti-immigration) to +100 (strongly pro-immigration). The idea was simple: if reclassified speeches really are marginal cases, they should cluster near zero on the thermometer. And if the LLM is doing something fundamentally different from RoBERTa, the thermometer would expose it.

It worked. Speeches where both models agreed on “anti” averaged around -54. Speeches both called “pro” averaged around +48. And the reclassified speeches — the ones the LLM moved from the original label to neutral — clustered closer to zero, with means of -25 and +2.5 respectively. The boundary cases behaved like boundary cases.

But something else showed up in the data. Something I wasn’t looking for.

Every score was a multiple of 25

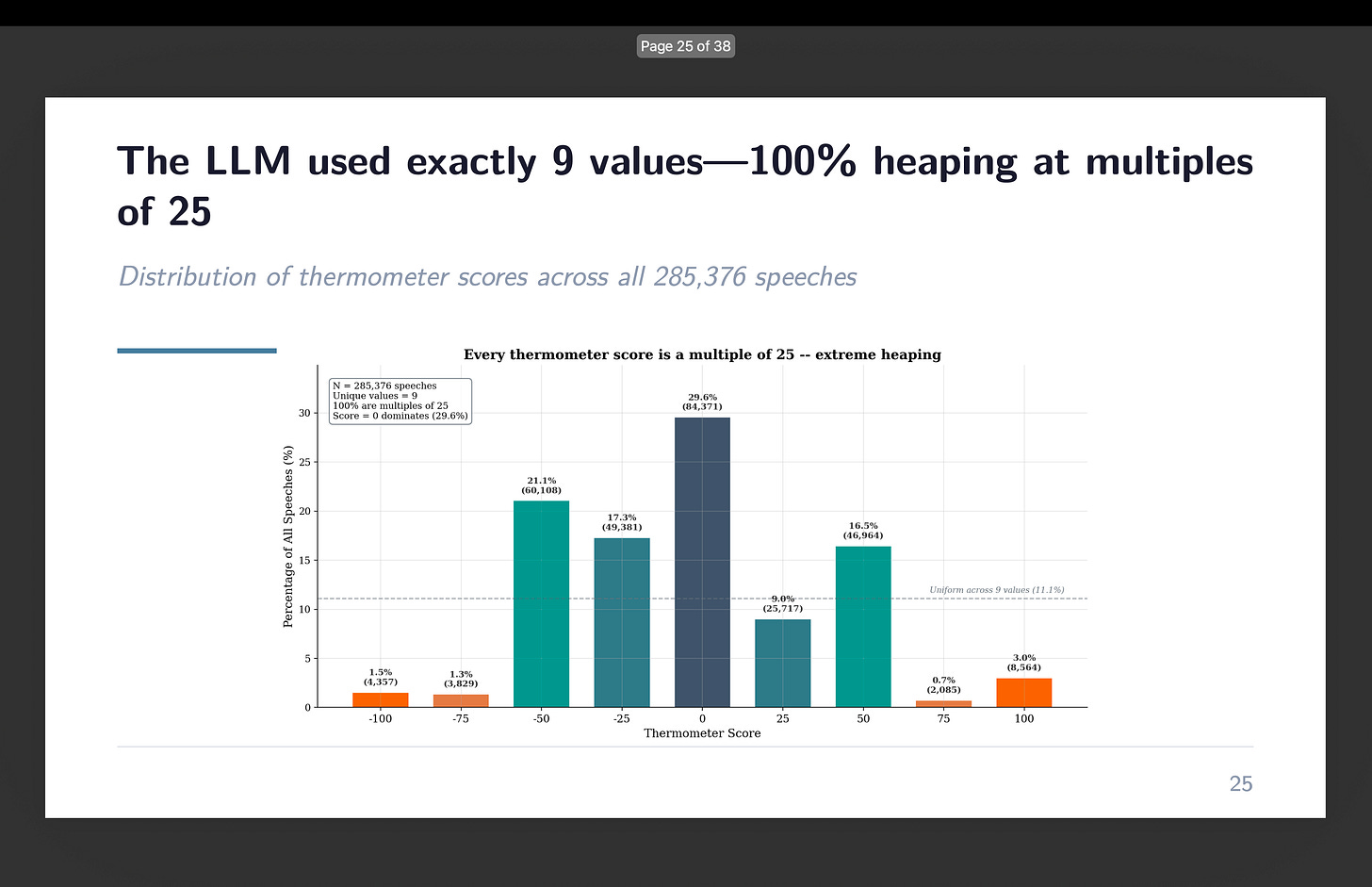

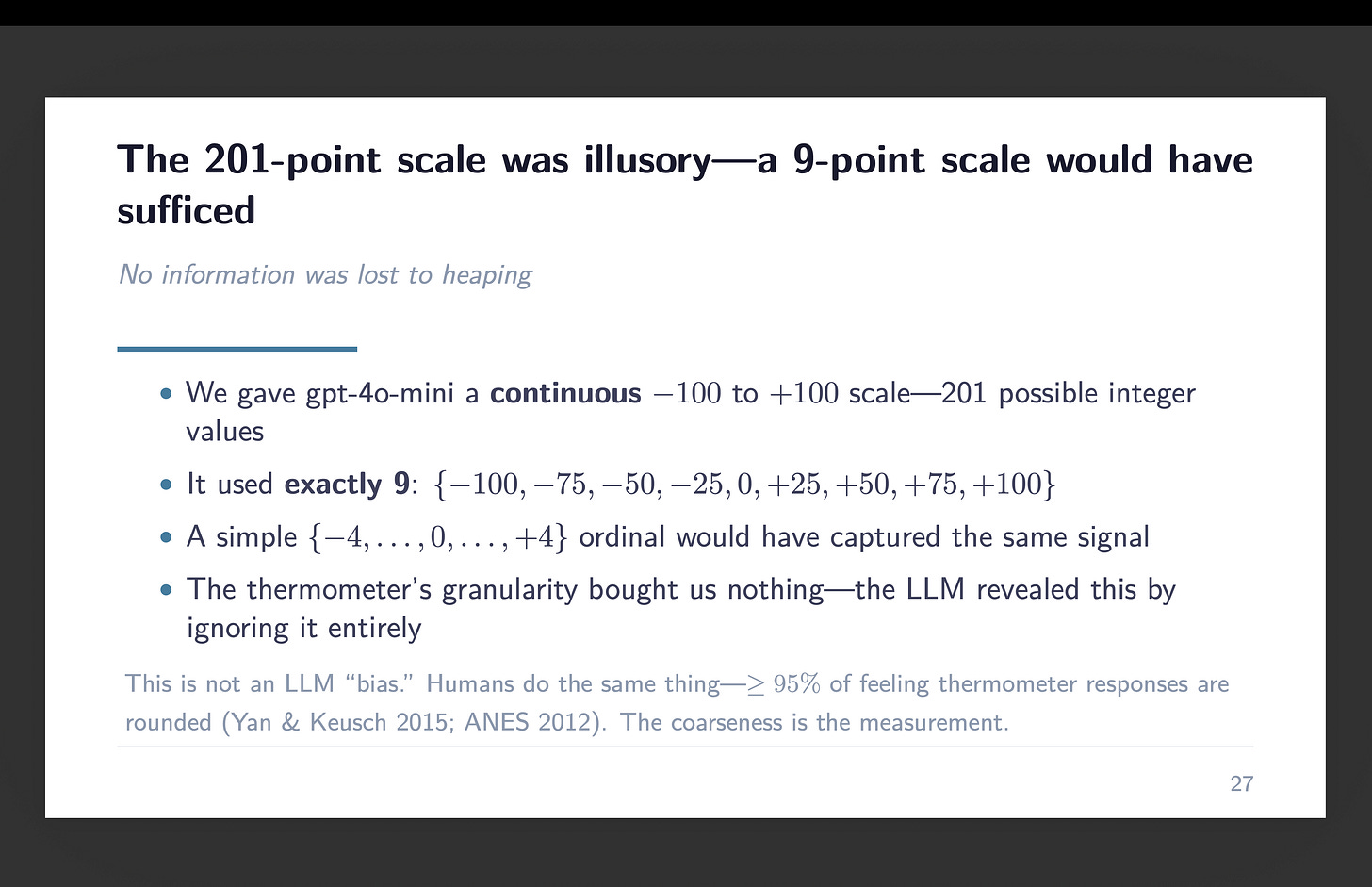

I gave gpt-4o-mini a continuous scale. Two hundred and one possible integer values from -100 to +100. And it used nine of them.

Every single thermometer score — all 285,376 of them — landed on a multiple of 25. The values -100, -75, -50, -25, 0, +25, +50, +75, +100. That’s it. Not a single -30. Not one +42. Not a +17 anywhere in a third of a million speeches. The model spontaneously converted a continuous scale into a 9-point ordinal.

When I saw this, I stopped the session. Because I recognized it. I had taught (my deck) about this just yesterday ironically in my Gov 51 class here at Harvard.

This is a known problem with humans

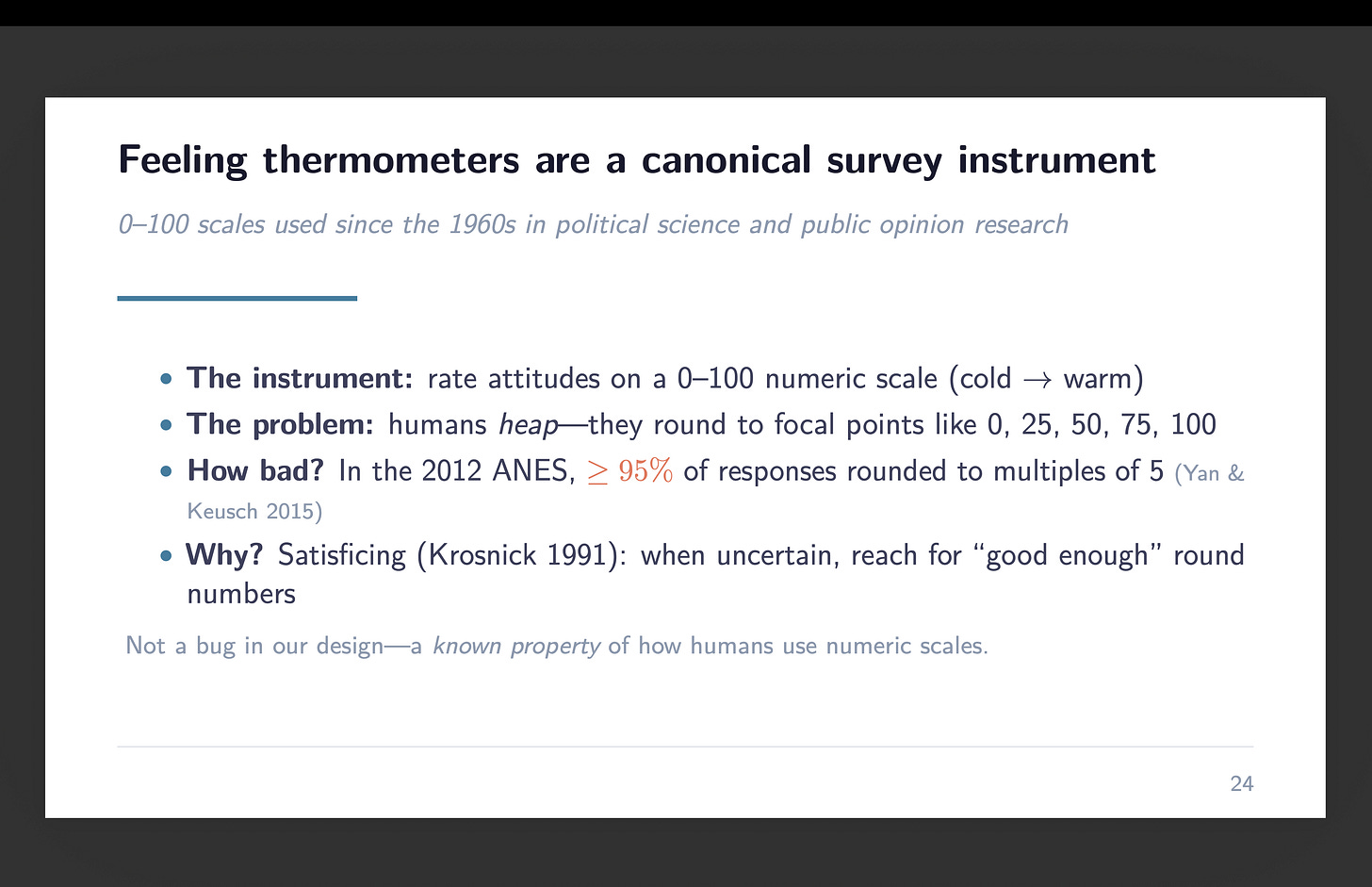

Feeling thermometers have been used in survey research since the 1960s. The American National Election Studies use them. Political scientists use them to measure attitudes toward candidates, parties, groups. You give someone a scale from 0 to 100 and ask them to rate how warmly they feel about something. The instrument is everywhere.

And the instrument has a well-documented problem: humans heap. They round to focal points. In the 2012 ANES, at least 95% of feeling thermometer responses were rounded to multiples of 5. The modal responses are always 0, 50, and 100. People don’t use the full range. They satisfice — a term from Herbert Simon by way of Jon Krosnick’s satisficing theory of survey response. When you’re uncertain about where you fall on a 101-point scale, you reach for the nearest round number that feels close enough.

This is so well-known that it became part of a fraud detection case. The day before I noticed the heaping in our data, I’d been teaching Broockman, Kalla, and Aronow’s “irregularities” paper — the one that documented problems with the LaCour and Green study in Science. Part of their evidence that LaCour’s data was fabricated involved thermometer scores. The original CCAP survey data showed the expected heaping pattern — big spikes at 0, 50, 100. LaCour’s control group data didn’t. It appeared he’d injected small random noise from a normal distribution, which smoothed the heaps away. The heaping was so expected that its absence was a red flag.

Nobody told it to do this

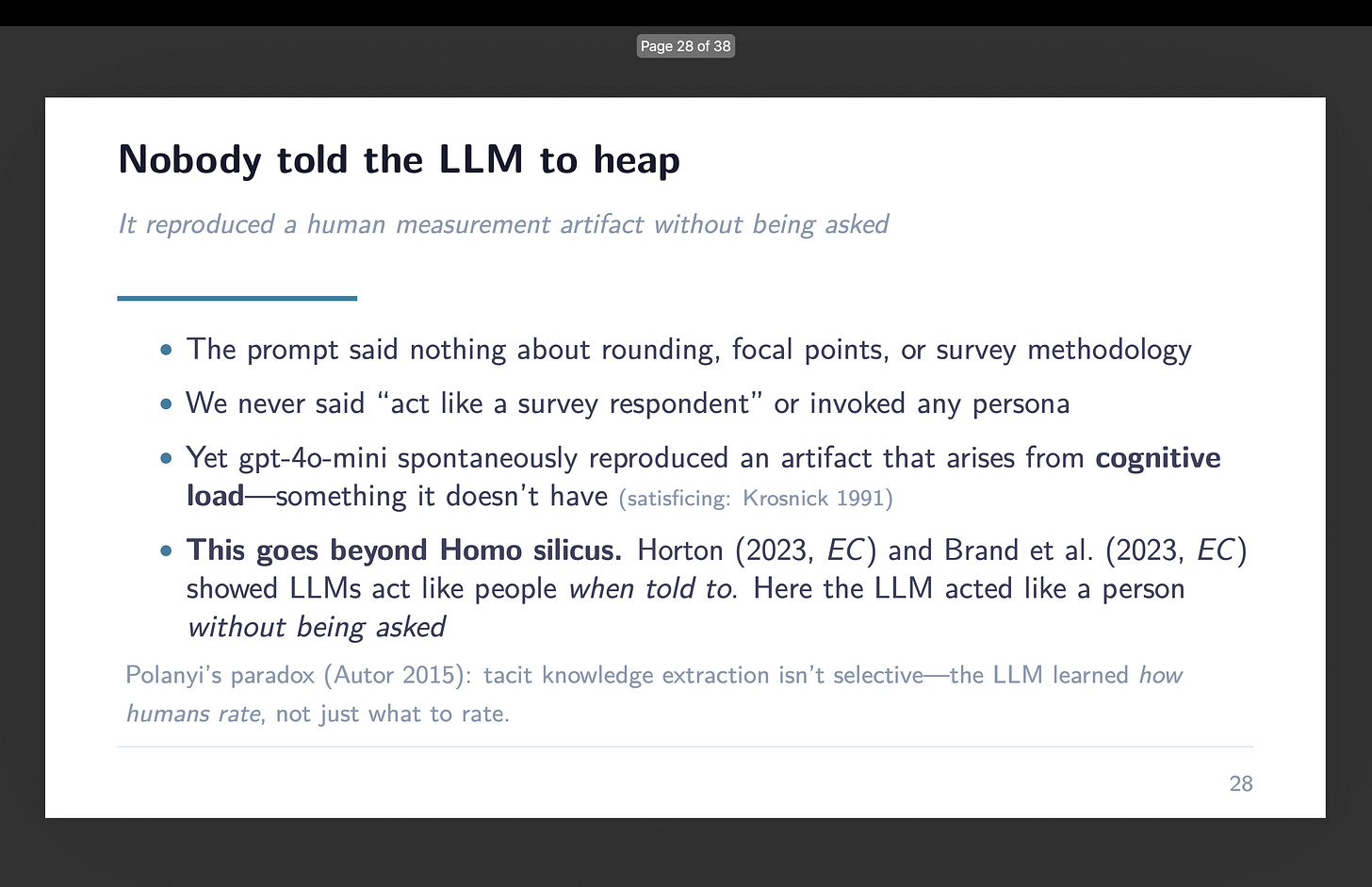

Here’s what stops me. The original Card et al. paper didn’t use a thermometer. RoBERTa doesn’t produce scores on a feeling thermometer scale. I invented the -100 to +100 framing for this project. The prompt said nothing about survey methodology, nothing about rounding, nothing about acting like a survey respondent. I gave gpt-4o-mini a classification task with a continuous output space and it voluntarily compressed that space in exactly the way a human survey respondent would.

The LLM doesn’t have cognitive load. It doesn’t get tired. It doesn’t experience the uncertainty that makes humans reach for round numbers. Satisficing is a theory about bounded rationality — about the gap between what you’d do with infinite processing capacity and what you actually do with a biological brain that has other things to worry about. The LLM has no such gap. And yet it heaped.

This goes beyond what others have documented. John Horton’s “Homo Silicus” work showed that LLMs reproduce results from classic economic experiments — they exhibit fairness norms, status quo bias, the kind of behavior we expect from human subjects — at roughly a dollar per experiment. Brand, Israeli, and Ngwe showed that GPT exhibits downward-sloping demand curves, consistent willingness-to-pay, state dependence — the building blocks of rational consumer behavior. Both of those findings are striking. But in both cases, the researchers told the LLM to act like a person. They gave it a persona. They said “you are a participant in this experiment” or “you are a consumer evaluating this product.”

I didn’t tell gpt-4o-mini to act like anything. I told it to classify speeches. And it classified them — correctly, usefully, in a way that replicates the original paper’s aggregate findings. But it also, without being asked, reproduced a measurement artifact that arises from human cognitive limitations it does not possess.

The tacit knowledge problem

David Autor has been writing about what he calls Polanyi’s paradox — the idea, from Michael Polanyi, that we know more than we can tell. Humans do things they can’t articulate rules for. We recognize faces, parse sarcasm, judge whether a political speech is hostile or friendly, and we do it through tacit knowledge — patterns absorbed from experience that never get written down as explicit instructions.

Autor’s insight about LLMs is that they appear to have cracked this paradox. They extract tacit knowledge from training data. They can do things no one ever wrote rules for because they learned from the accumulated output of humans doing those things.

But here’s what the heaping suggests: the extraction isn’t selective. When the LLM learned how to evaluate political speech on a numeric scale, it didn’t just learn what to rate each speech. It learned how humans rate. It absorbed the content knowledge and the measurement noise together, as a package. The heaping, the rounding, the focal-point heuristics — these came along for the ride. Nobody trained gpt-4o-mini on survey methodology. Nobody labeled a dataset with “this is what satisficing looks like.” The model learned it the way humans learn it: implicitly, from exposure, without anyone pointing it out.

I suspect this is the kind of tacit knowledge Autor has in mind. The things no one ever told anyone to do, because no one knew they were doing them.

The stress test

There was also a practical question hanging over the whole project: does any of this depend on the fact that we had three categories? Pro, anti, and neutral form a natural spectrum with a center that can absorb errors. Maybe the symmetric cancellation only works because neutral sits between the other two.

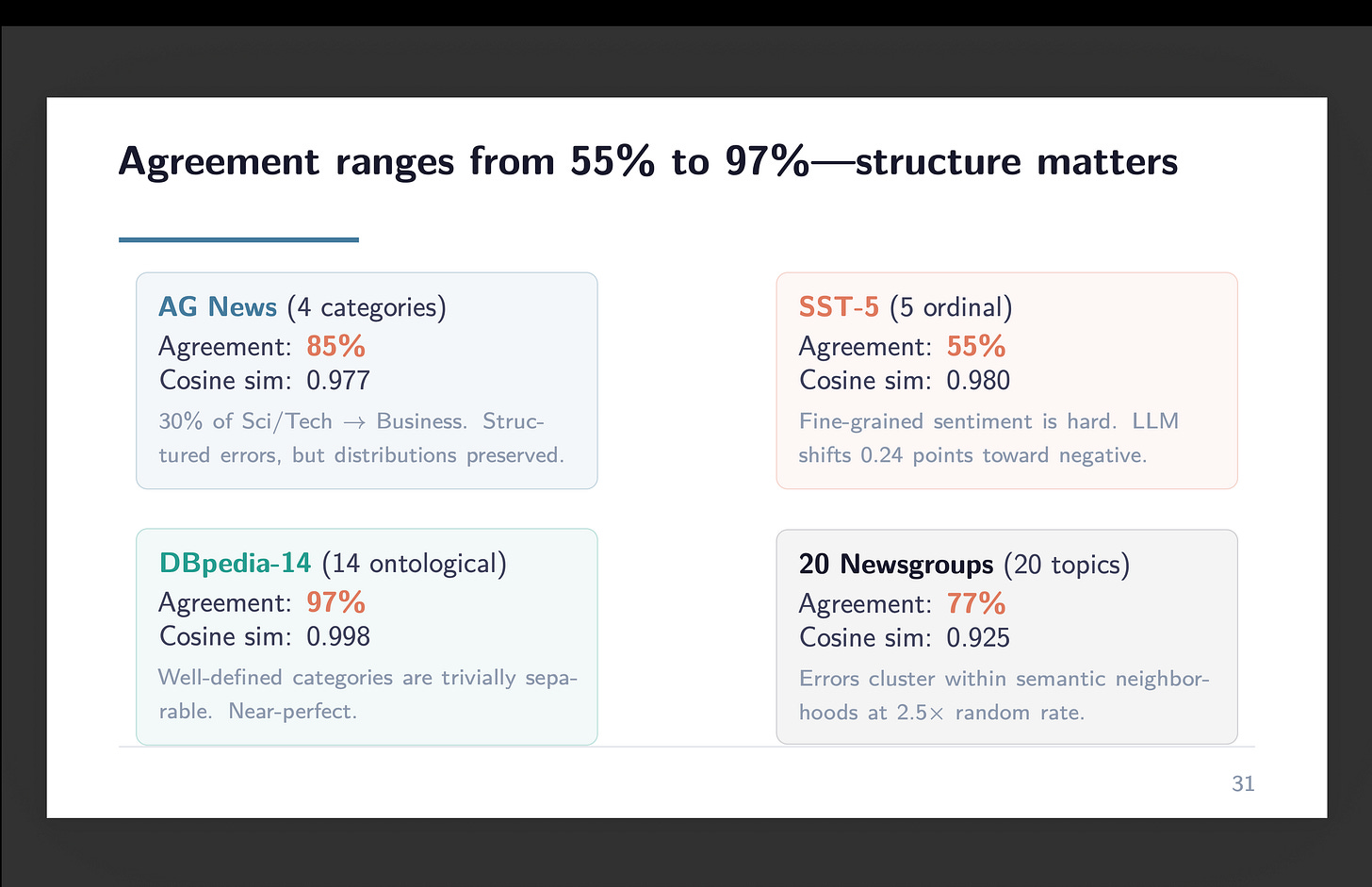

So we tested four benchmark datasets: AG News (4 categories, no ordering), SST-5 (5-level sentiment with a center), DBpedia-14 (14 ontological categories), and 20 Newsgroups (20 unordered topics). Same methodology — zero-shot gpt-4o-mini, temperature zero, Batch API. Total cost for all four: a dollar twenty-six.

Agreement ranged from 55% on 20 Newsgroups to 97% on DBpedia-14. The mechanism wasn’t tripartite structure. It was category separability — how distinct the categories are from each other. When the categories are semantically crisp (company vs. school vs. artist in DBpedia), the LLM nails it. When they’re fuzzy and overlapping (distinguishing talk.politics.guns from talk.politics.misc in Newsgroups), it struggles. The immigration result generalizes, but not because three categories are special. It generalizes because the categories happen to be reasonably separable.

GPT as measurement tool

One more thing. While we were doing this work, Asirvatham, Mokski, and Shleifer released an NBER working paper called “GPT as a Measurement Tool.” They present a software package — GABRIEL — that uses GPT to quantify attributes in qualitative data. One of their test cases is congressional remarks. The paper provides independent evidence that GPT-based classification can match or exceed human-annotated approaches for the kind of political text analysis we’ve been doing.

I mention this not to claim priority but to note convergence. Multiple groups are arriving at the same place from different directions. The LLM isn’t just a classifier. It’s a measurement instrument. And like all measurement instruments, it has properties — including properties nobody designed into it.

What the pizza taught us

I started this series wanting to show people what Claude Code can do. I still think the best way to learn it is to watch it work on something real. But the something real kept producing surprises. The 69% agreement that doesn’t matter because the disagreements cancel. The thermometer scores that cluster at the boundary. And now this — a measurement artifact that nobody asked for, that nobody programmed, that emerges from the same tacit knowledge that makes the classification work in the first place.

A 9-point scale hidden inside a 201-point scale. The LLM measures like a human, down to the mistakes. And I don’t think it knows it’s doing it any more than we do.

So now what?

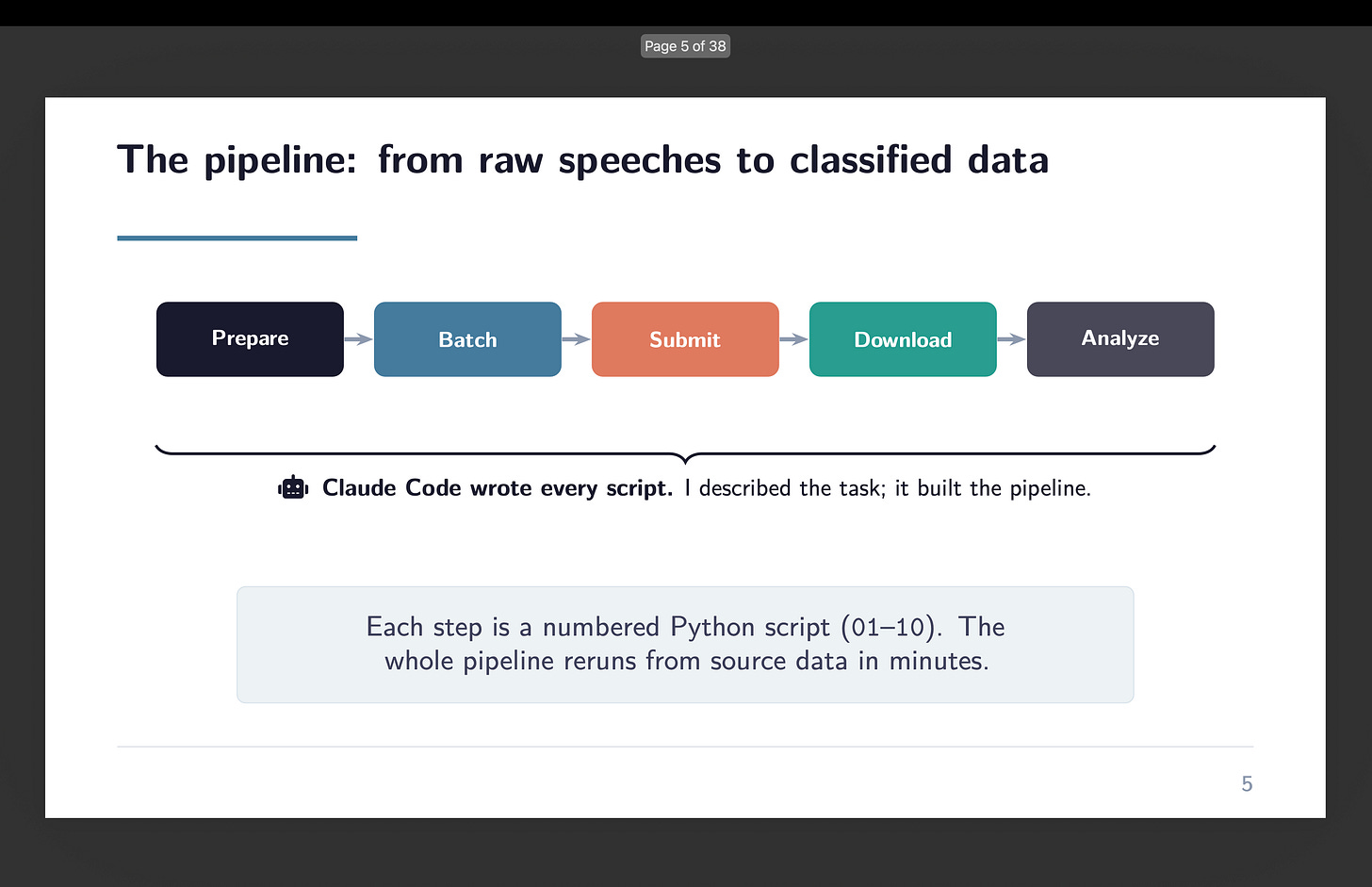

Well, that’s the end of this replication/extension of the PNAS paper. I wanted people to see with their own eyes the use of Claude Code to do classification of texts using gpt-4o-mini at OpenAI. It’s not a straightforward thing. Here are two slides about it:

And so that’s done. I hope that the video walk throughs, and the explanations, as well as the decks (like this final one) have been helpful for some of you on the fence about using Claude Code. Not only do I think that it is a helpful productivity enhancing tool — to be honest, I suspect it’s unavoidable. It’s probably on par with the move from using punch cards for empirical work to what we have now. Maybe even moreso. But having materials that help you get there I think is for many people really vital as most of the material until recently was by engineers for engineers, and frankly, I think Claude Code may be putting those specific tasks into pure automation meaning even those explainers could fade.

But now I have to figure out what I’m going to do with these findings! So we’ll see if I can figure out a paper out of all this bumbling around that you saw. Not sure. I either am staring right at a small contribution or I am seeing a mirage and nothing is there, but I’m going to think on that next. I’m open to suggestions! Have a great weekend! Stay hydrated as the flu may be going around.

This whole process has been an inspiration for my research and use of agents Scott. I say that without prejudice or hyperbole and thank you for writing with your characteristic humility. 🙏 also, would 💯 read that paper if you write it.